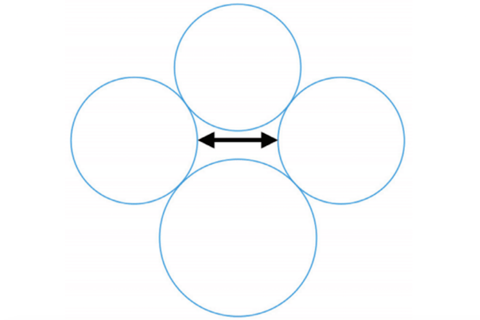

Luthier Kevin Kelly explains his ‘Four Circles’ system for instrument design, adaptable to violins, violas and cellos

This is an extract from an article inThe Strad January 2019, in which luthier Kevin Kelly describes his geometrical method for violin design. To read further, download the issue on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

For those who study classical violin making, there are some deep mysteries about the way classic Cremonese violins look. The first – and, in my view, the most important – is that there is something about their look that is unmistakably organic. They somehow appear to have ‘grown’ into their shapes.

Rather than looking like carved objects, some instruments appear almost as if they are the shell of some kind of living creature that has long since departed this earth, but has left behind a beautiful concrete memento.

Another mystery is that there appears to be a ‘family resemblance’ among instruments from different makers of the Cremonese school – even across types of instruments and generations, so that there is a recognisable quality in the look of Cremonese violins, violas and cellos, even though they may be different types of instruments made a century or more apart.

Connected to this idea, there are related schools of making that are not Cremonese, but which similarly have the same kind of family resemblance. They also have an organic quality, but are clearly not Cremonese – for example, the schools of Brescia, Venice and Milan.

Another way to look at it is that there must be a system of design that works in a way that is somewhat analogous to the way DNA works

In some cases these designs are quite sophisticated and elegant, even though the work itself might betray a very hasty construction. To me, these traits suggest that there must have been a system of design that makers could easily understand and follow, with an order of operations in which one feature always followed another in a rational, step-by-step fashion.

Another way to look at it is that there must be a system of design that works in a way that is somewhat analogous to the way DNA works, albeit in a very limited way.

A system of design with a strictly limited number of parts and relationships would explain how instruments made by different makers, decades apart, could compose designs that are similar, and also how accomplished makers who were apparently content – or resigned – to otherwise do lesser work could nevertheless come up with designs of surprising sophistication, beauty and vitality.

This is an extract from an article inThe Strad January 2019. To read further, download the issue on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

No comments yet