Philip Kass gives his thoughts on Claudio Amighetti’s investigation into the lives of Turin maker Nicola Giorgis and his daughter Francesca Maria, published in the November 2024 issue

In the November 2024 issue of The Strad, Claudio Amighetti presented his research into the lives of the Giorgis family, primarily Nicola (1678-1745) and his daughter Francesca Maria (1716-74). The article presents evidence that following Nicola’s death, the workshop passed to Francesca Maria, who managed it successfully for a number of years and may even have made her own instruments there. Here, violin expert Philip Kass adds his own thoughts to Amighetti’s conclusions and gives some background history on the circumstances of Turin residents’ lives during that period.

Since I was scheduled to spend several weeks in Turin, conducting my own researches, I decided to check some of the documents cited by Claudio Amighetti as sources to see how I interpreted them. In the process, I studied the central premise of the article and came up with a far more nuanced picture of those events.

A key concern in those days, as in ours, was the matter of inheritances and property. What was very different in those days was that wives had very little authority or control over family property, indeed, what was theirs coming into the marriage technically became their husband’s once the vows had been exchanged. This is one of the reasons why in last wills of those years, the dying husbands inevitably acknowledged the dowry contracts with their wives as well as identified all of their children, legal or otherwise. In this way, those families had some resources to fall back on that were freed from whatever debts or liens that husband might have incurred in life.

A further nuance concerned children under the age of majority. Their welfare was overseen in Turin by the Royal Senate, whose powers included the disposition of family resources and who frequently stepped in to assign guardians to families when the surviving spouse did not appear to have the means to provide for them. This could have good repercussions or bad, but more importantly it took the control out of the hands of a family and placed them into someone else’s.

This appears to have been the circumstances surrounding the events of 1745 for the Giorgis family. Nicola Giorgis was elderly; he had no surviving children other than his daughter Francesca, and she in turn was the mother of three minor children. By enunciating that Francesca specifically was his sole heir, Nicola guaranteed her some means of support for herself and her family. And this was quite possibly done because her husband Giuseppe Pellegrini was also ill, perhaps from the same disease, as indeed both died within a few weeks of one another. In her husband’s testament, he repeats and reaffirms that ownership of the family property, in her name, and like his father-in-law, specified the workshop adjoining the family home.

Read: Like father, like daughter: the Giorgis family of violin makers

Book review: The Piedmontese Violin Makers in the 17th and 18th Centuries by Claudio Amighetti

As a widow with minor children, this now passed on to the purview of the Senate, and so, not surprisingly, there was yet another act, a few months later, in which Francesca’s guardianship of her children, and her means to care for them, was reasserted in a notarized legal act for presentation when the case came to judgement.

This was critical for Francesca, and not just for herself and her children. If she should remarry, her property would likely become the property of her new husband, who may or may not provide care and sustenance to her children through Pellegrini and instead direct those means to children from his prior marriage or those who might arise from his union with Francesca. So, it became essential for her to make clear in the dowry agreement that her property was distinct from his, and distinct from any family wealth being brought into the marriage, so that she and her children would be protected. This came to the fore with her remarriage in 1749, and while those previous testaments all mentioned a workshop, only this action specifies exactly what its purpose was.

So did she make violins? It’s plausible, but there are other possibilities. The first is one I describe with the name Veuve Clicquot. The widow Clicquot may or may not have engaged in champagne production, but she did operate a winery, and employed those who did, and did so very well indeed. A more recent case of this can be seen in Luigia Bertero, widow of Antonio Guadagnini, who continued to run his shop, to the consternation of their son Francesco, from her husband’s death at Christmas 1881 until her own death in 1894. However, there is another question needing answers: where are the instruments?

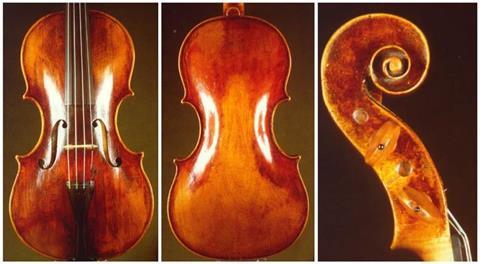

In my career, I have found that the numbers of authentic works by luthiers working in Turin in the 17th and 18th centuries is shockingly small. Those makers might have been engaged in repairs, or strings, or the making of fretted instruments, but there are few bowed stringed instruments to tell us much about their industry. I have encountered just two instruments that appeared to have authentic labeled of Nicolo Giorgis, and they were both from earlier periods. The two illustrated I have not seen, nor can I attest to whether their labels were correct. As we know in the trade, the label is the easiest part of the instrument to replace or to alter, and there could be a body of work traceable to that shop that has been traveling under other identities.

My researches have also illuminated another issue, that of handwriting, and I have found Piedmontese and Ligurian numbers to be both hard to read and easy to misinterpret. I also note that by the later 1700s, the trade in bowed strings seems to have been collapsing in that region, with the local craftsmen shifting over to the production of guitars and mandolins, neither of which have come down to us in quantity simply because their construction does not favor long endurance or simple repair. And so, our interpretation of events must, for now, remain uncertain.

However, in closing, there is one other thought that comes to mind in these matters. In those days, society functioned through an understanding that the wife was completely subservient to the husband, and God help the wife who chose to assert herself outside of her socially accepted spheres. This is something our modern age should never forget. Today we are living in the Golden Age of violin making, with more great violin makers working today than in the entire history of the craft, and a highly significant proportion of their ranks are women. While it is good that we recognize the contributions made back then by women to those arts and crafts that we cherish today, we must be very aware that not one thing we say or do will make the lives of those living centuries ago one bit easier. On the other hand, we can materially improve the lot of today’s luthiers by giving them our respect and especially our commerce, and in the process give them the recognition, now and in the future, that their achievements so warrant.

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stringed instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet