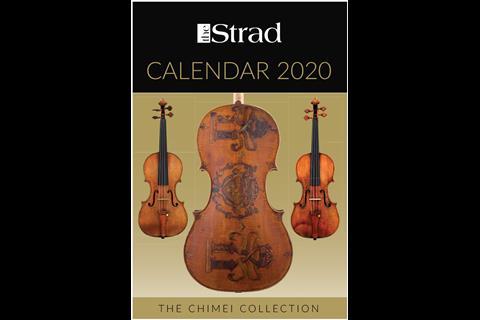

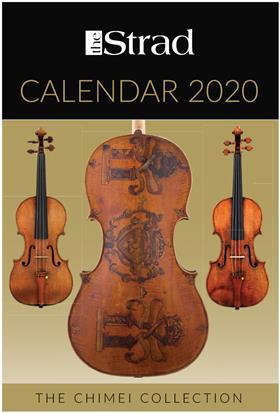

The Chimei Museum in Taiwan houses the largest collection of stringed instruments in the world.The Strad Calendar 2020 marks 30 years since its founding, as Dai-Ting Chung and Andrew Guan highlight some of the remarkable treasures within its walls

In 1990 the Taiwanese–American violinist Cho-Liang Lin sold his instrument, the 1707 ‘Dushkin’ Stradivari, to Shi Wen-long, the founder of Taiwan’s Chimei Corporation. It was to be the first purchase of a fine, important instrument by the newly established Chimei Foundation, and the beginning of a collection that now numbers more than 1,370 stringed instruments from 1,120 different makers over five centuries and across six continents.

When Shi Wen-long is asked about his motivation for such unreserved support and investment, his answer is always the same: he wants to offer makers and musicians as many fine-quality instruments as possible, for both research and performance. On average, Chimei lends out about 260 instruments annually for exhibitions, concerts and music competitions.

The collection is not only the broadest in the world, but also the deepest. It contains, for instance, a full quartet by Andrea Amati – and given that only five cellos and five violas by the maker survive today, plus no more than twelve violins, putting together a quartet was indisputably a tall order. Given the times at which they were made, not even Amati himself could have heard them playing together in Cremona 450 years ago.

It took Chimei eight years to acquire the foursome in the end. Quite often, to acquire them from their owners Chimei had to purchase another rare and highly sought-after masterpiece whose market value was even higher, and which then was exchanged for the Andrea Amati. This often proves to be the case: owners of precious instruments do not ask Chimei for money, but rather ask to exchange them for other instruments of similar value.

In compiling The Strad Calendar marking 30 years since the ‘Dushkin’ purchase, the decision was made to focus on the Cremonese masterpieces owned by the foundation; however, the collection contains many ‘first’ or ‘earliest’ instruments that could easily have filled a calendar by themselves. There is a violin made in America in 1915 by Situ Meng-yan (1888-1954), thought to be the first ever Chinese violin maker; one by Jacob Rayman (c.1596–c.1660), one of the first in England; a cello by Abraham Prescott (1789–1858), the earliest cello made in the US; and a dragon-head violin by Marcin Groblicz (c.1540–1609), the founder of the Kraków School in Poland.

Recently, Chimei has added a new kind of string collection to its offering: it acquired from Italy the entire workshop of Mantua makers Stefano Scarampella and Gaetano Gadda. This includes many of their patterns, moulds and tools, as well as instruments in the white, and remaining wood stock. The workshop is now displayed in a large glass viewing room in the museum, adding another dimension to the study of this important firm.

Chimei also has one of the largest databases of stringed instruments in the world, with over 912,000 pages of instrument-related documents and more than 100,000 instruments and bows electronically archived. It is now developing a new search algorithm to help users locate an instrument quickly. The project has been ongoing for nearly a decade. The basic idea is to create a file for each instrument, which includes descriptive attributes that are searchable by text. The algorithm works similarly to how hashtags are used on social media: database users can search for a particular set of instruments based on one or more attributes. For example, typing in ‘# Serafin + #OB’ instantly returns all violins made by Santo Serafin with bird’s-eye maple backs. The plan is to make the database open-source, and capable of quick and easy sharing.

Every fine instrument is a unique traveller, surfing the waves of time from one mortal keeper to the next. Like any owner, Chimei sees itself as playing the role of a temporary keeper in the grand scheme of history. Knowing that an instrument’s time is limited, the foundation is diligent in exploring new frontiers for the study and research of stringed instruments, hoping to leave a legacy for future generations.

’Every fine instrument is a unique traveller, surfing the waves of time from one mortal keeper to the next’

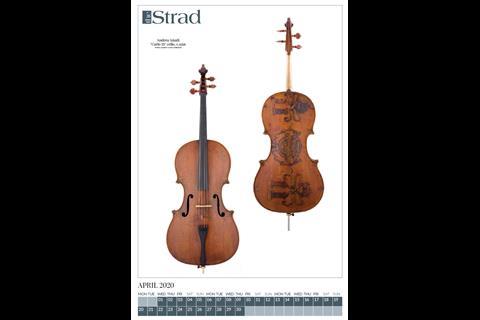

The 1566 ‘Carlo IX’ cello by Andrea Amati is the oldest bowed stringed instrument in the Chimei collection, and Alfred E. Hill once wrote that it was ‘the oldest cello known to me’. Its Hill certificate of 1926 states that it has been ‘considerably reduced in size both at the joint, and the outline’. The narrowing operation entailed the removal of a strip of wood along the centre joint; in addition, the body was reduced by the removal of wood all around the borders. The head is not original.

The cello was examined in 1927 by the Buvelot firm of Paris, and its appraisal states that the decoration shows characteristics typical of 16th-century Italian painting techniques. The decoration includes the date of 1566, which appears undisturbed on a Roman column on the lower bouts.

The 1595 ‘Henry IV’ viola by Girolamo Amati is a robust instrument of red–brown colour. Covering most of the one-piece maple back is a painting of the armorial bearings of the French King Henry IV, supported on each side by an angel. At each end of the back is a gold letter ‘H’ surmounted by the crown of France. Both designs are topped by laurel leaves. Geometrically spaced throughout the back are six burning flames. Painted on the maple ribs is the Latin inscription, “DVO.PROTEGIT.VNVS “ (’One protects two’, signifying the king’s authority over the two kingdoms of France and Navarre). This motto progresses around the sides from left to right.

The present body length is 422mm, but according to the Hill papers, was probably 457.2mm (18 inches) or longer before it was cut down in c.1800. The British expert Peter Biddulph has said that the instrument has been repurposed as many as three times: once during its early history; a second time in c.1800–1815; and a third time in c.1880. A scientific examination of the painting and the pigments has yet to prove this. Again, the head is not original.

The 1656 Nicolò Amati violin is still in mint condition. Nicolò started to convert previous violin patterns into his ‘Grand Pattern’, of which this is an example, in the 1650s. This well-preserved violin is typical of his work, and its sound is clear and attractive. Nicolò’s later followers regarded the Grand Pattern as the standard of violin making and their efforts, either by inheriting, refining or innovating this model, brought the craft of lutherie into a splendid era. The Grand Pattern is among the jewels of violin making history.

The ‘paganini’ is one of the most representative works of ‘filius Andreae’

The little-known 1667 ‘Dubois’ violin, from Stradivari’s early period, still has its original label bearing the date and is thus undoubtedly one of the earliest instruments to have been made by the master at his newly founded workshop in the Casa Nuziale. In this violin, Stradivari’s style is still very much oriented towards that of contemporary Cremona but is full of new, individual ideas and differs stylistically from Amati models in several ways. The f-holes, for instance, are more reminiscent of Rugeri’s style.

Apart from the stunning craftsmanship already evident in this work, the instrument’s varnish is of considerable interest: firstly, because it is still largely intact; secondly, since it is exemplary of Stradivari’s honey-coloured varnish, which was based on the Amati tradition. An interesting detail that can also be found on this violin is the presence of a small wooden dowel on each side of the pegbox, filling the holes that once contained a guiding rod for the A and D strings.

Girolamo II made his c.1685 violin before he left Cremona. Basing it on the Grand Pattern, he cut down the size and added some of his own characteristics – for example, the enlarged f-holes, the purfling inlaid more freely, and C-bouts that curve in somewhat more deeply. This violin reveals little influence of Girolamo’s father Nicolò, owing to the latter’s early death in 1684. Girolamo II was no better in craftsmanship or material selection than either his father or other apprentices in the workshop; however, the tonal quality and sonority of his instruments maintained the century-old family tradition.. The violin’s head is by a later maker.

The mint-condition violin made during Giuseppe Guarneri ‘filius Andreae’s middle period bears an original label dated 1706. Unlike his father, Giuseppe didn’t use golden-brown varnish but instead chose the red that prevailed at the time. This masterpiece is one of the most representative works of ‘filius Andreae’. Nicolò Paganini bought this violin from a Mr Passini of Parma in 1795. It was then purchased from the Paganini estate by the famed Finnish collector Harry Wahl.

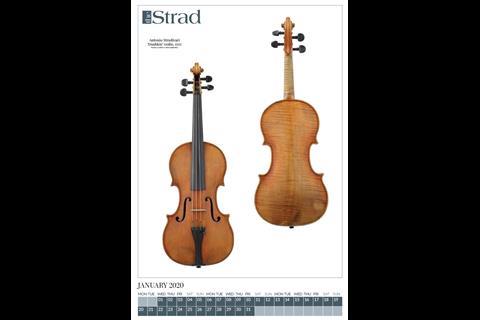

Stradivari’s ‘Dushkin’ violin bears an original label dated 1707, and this year of production is supported by the dendrochronological examination of the instrument, which dates the youngest growth ring to 1693. It takes its name from the American violinist and composer Samuel Dushkin (1891–1976), who purchased the violin in 1926. On 23 October 1931 Dushkin used his Stradivari to perform the premiere of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto in D major, which took place in Berlin. In 1983 it was the first Stradivari to be purchased by the US violinist Cho-Liang Lin. He performed on the violin for seven years before selling it to the Chimei Foundation.

In 1782 the violinist G.B. Viotti (1755–1824) amazed the audience at his debut in Paris by performing on the 1709 Stradivari violin now known as the ‘Viotti, Marie Hall’. Since then, European violinists and collectors have enthusiastically collected Stradivari violins, greatly admiring their gorgeous sonority. In 1905 the British violinist Marie Hall bought this violin via the London dealer George Hart, and played on it during her extensive international touring engagements.

The violin bears its original label, and its body length is 356mm. The extraordinarily beautiful one-piece maple back has a medium-width flame, which slants from the upper right to the lower left. This amazing maple wood was acquired by Stradivari in 1709. From 1709 to 1716, Stradivari used this very same maple wood to make several violins. The ribs of this instrument are finely figured, and the scroll is curled with flames from medium to broad width. The varnish is an exuberant orange-brown.

The Bergonzi cello is one of just two known to have been made by him

From 1726, Stradivari began developing a small cello size, which we call the ‘Forma B picola’. The ‘Pawle’ cello, dated 1730, was built on this new model. Antonio was already 86 years old at that time, and it is therefore said that much of the work must have been undertaken by his apprentices. The ‘Pawle’ is presumed to be one of the instruments brought to J.B. Vuillaume in Paris by the celebrated collector Luigi Tarisio. Named after the British collector Frederick Pawle, it is substantially well preserved. The tone quality is excellent with the higher pitches being most impressive. Most of the reddish-brown varnish is still intact with the astonishing texture that is so typical of 1730s Stradivaris. The body is 746mm in length.

The recently discovered 1735–45 Carlo Bergonzi cello is one of just two that are known to have been made by the luthier. Like the ‘Pawle’, it was built on a the Forma B picola, but while the model is Stradivari’s it is covered with an orange varnish typical of Bergonzi. The locating pins at the extremities of the back are faceted in the Bergonzi style and set inside the purfling. The exterior surfaces of the ribs have toothed plane markings throughout. The f-holes have large upper holes and are somewhat more open. The head of the cello is by a later maker. The body is 714mm in length.

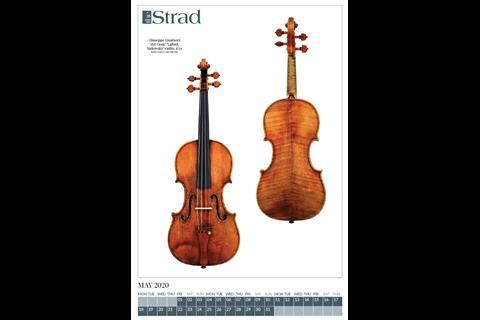

Finally, we come to Guarneri ‘del Gesù’. The 1733 ‘Lafont, Siskovsky’ exhibits the maker’s independent style, which by this time had fully emerged. The outline has a certain flatness leading into the corners, which would become a distinctive feature in coming years. The f-holes have larger eyes than his earlier violins and would continue to expand. It is interesting that the maple used on the back of the ‘Lafont, Siskovsky’ is as fancy as that seen in Cremona at any time. It can even be compared with the wood from the best years of the Stradivari workshop. Overall, this violin shows original expression, yet is crafted in a controlled and refined manner.

The ‘Lafont, Siskovsky’ gains its name from the great French violinist Charles Philippe Lafont who owned a pair of Guarneris until his death in 1839. Jaroslav Siskovsky played it for nearly 40 years until it was purchased from him by the violinist Erick Friedman. In 1976 the Italian virtuoso Salvatore Accardo acquired it through Parisian dealer Étienne Vatelot, and used it to record Paganini’s 24 Caprices.

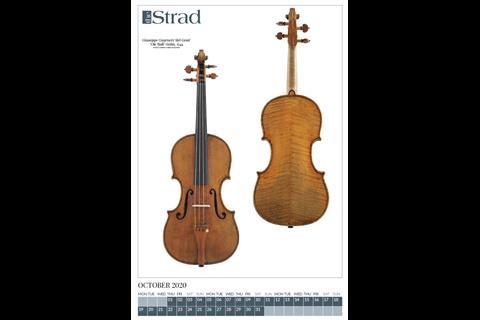

The 1744 ‘Ole Bull’ is considered the last great work of ‘del Gesù’. With its powerful sonority, it was called his ‘most characteristic masterpiece’ by the Hills. Its plain arching not only exerts the dark and abundant tone colours of the Brescian school but also the characteristic resonant sonority of Cremonese violins. The cutting of the f-holes and scroll is a vivid example of the luthier’s unique design and perpetual creativity. The ‘Ole Bull’ still bears its original label. With a body length of 352mm, the back is of two-piece maple with yellowish-orange varnish. According to a dendrochronology analysis, the two-piece front is made from two asymmetric pieces of spruce of different ages. The bass side is almost identical to the 1740 ‘Heifetz’; the treble side, however, is exactly the same as the 1743 ‘Sauret’.

The violin was once owned by the famous Norwegian violinist Ole Bull (1810–80) who was a hero in the Norwegian national movement. Ole Bull made every effort to promote Norwegian music and this was his favourite violin.

Reference

No comments yet