In 2022, Annalisa Pappano bought a six-string pardessus from a reputable dealer that turned out to be stolen from a Belgian museum. She shares her turbulent story, in an aim to raise awareness of issues related to stolen instruments and the potential pitfalls for musicians

Discover more lutherie articles here

The treble range of the viola da gamba family has long held my attention, perhaps due to my background in violin. My particular interest lies in the pardessus de viole, a hybrid combination of violin and viola da gamba played predominantly by ladies in 18th-century France. I have spent years playing a beautiful antique five-string pardessus, but I had always hoped to find an antique six-string instrument—the earlier and much rarer form of the instrument.

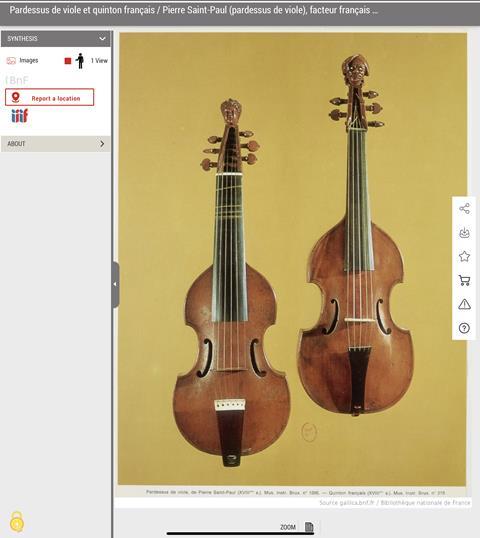

In 2022, an opportunity to acquire such an instrument presented itself. A colleague in France informed me about a six-string pardessus offered by a reputable dealer in Paris: a 1742 Pierre Saint-Paul, in original condition, complete with a case made by the maker’s son. The rarity of the instrument, combined with its untouched state, made it an exceptional find. I decided to bite the bullet and proceed with the purchase.

Over the course of the next month, I played four concerts with the pardessus, and it performed beautifully. The opportunity to work with an instrument in its original setup provided an invaluable learning experience. It was also exciting to share my news with scholar/luthier friends: Tom MacCracken (who compiles a database of historical violas da gamba in public and private collections, available on the Viola da Gamba Society of America website) and Francis Beaulieu (a Montreal-based luthier who has built and restored several pardessus). It was exciting to see this newly-discovered instrument added to the database of historical viols and to share the instrument with a fine luthier who is interested in the pardessus.

During this period, together we encountered an online image, taken from a book, of a similar Saint-Paul pardessus that was made in the same year (1742). It was part of a collection of the Brussels Musical Instrument Museum. Initially, we believed this to be a coincidence, though the details of the tailpiece and scroll were strikingly alike. Upon closer inspection, it became evident that the two instruments were not merely sister instruments, but they were the same. The presence of a small chip on the scroll, visible in both my instrument and the photograph, confirmed it.

Tom discreetly contacted a museum curator to inquire about their instrument, and we discovered that it had been stolen from the Brussels museum in 1980. The pardessus in my possession was, in fact, the stolen item. It would always be considered property of Belgium, since there was no statute of limitations.

Faced with this knowledge, it was clear that I had no choice but to return the instrument. I contacted the dealer, who was horrified by the revelation. She investigated and learned that the pardessus had passed through several hands—one being an antique shop near the museum—before coming into her possession. She would reimburse me for the cost of the purchase of the instrument upon its return to the museum. However, I was understandably anxious about whether I would be reimbursed, given the complexities of the situation.

The return of the instrument was a difficult process. Before doing so, I performed one final concert with it, during which I shared the story with the audience. The final performance was sombre, knowing that my instrument would never again be played but instead returned to a museum display.

I traveled to Brussels shortly thereafter, returning the instrument to the Musical Instrument Museum. The museum staff were understanding and lovely, and they even invited me back to perform a concert on a different instrument at a later date. They also conducted an inventory of their collection, identifying other items that had been stolen over the years, and began working to share this information with dealers and those involved in the antique instrument market. My case has since contributed to broader discussions about the need for a centralised database of stolen and missing instruments—though the implementation of such a system presents significant logistical and financial challenges.

In hindsight, I was fortunate to discover the provenance issue early in my ownership. Had more time passed, it is likely that recovering my financial investment would have been far more complicated, if not impossible. As it stands, I was reimbursed in full by the dealer, and I have since acquired another antique six-string pardessus, which I continue to use in concerts.

This experience has highlighted the complexity and risk involved in purchasing antique musical instruments (or even antiques of any sort). While I was aware of issues surrounding looted musical objects, such as those associated with Nazi-era theft, this situation has underscored the importance of due diligence in researching the history of any instrument, regardless of its apparent legitimacy.

All photos courtesy Annalisa Pappano.

Read: My whirlwind journey to owning a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’: David Garrett

Read: Cello of Holocaust victim reunited with daughter after 80 years

Discover more lutherie articles here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stringed instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet