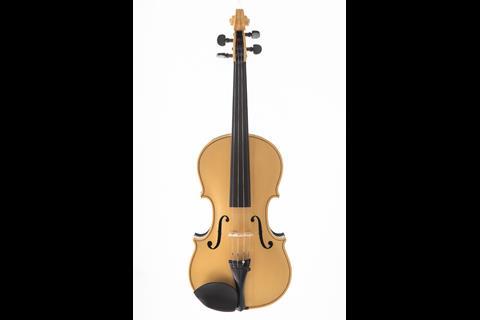

Made from 5,000-year-old wood, the instrument can lay a claim to being ‘the oldest violin’ - despite being made two years ago. Nigel Wardle talks to maker Philip Taylor

Discover more lutherie articles here

In 2012, a huge sub-fossilised Bog Oak, (also known as ‘Black Oak’), was discovered at Wissington Fen in Norfolk. It was the biggest and best example ever found. Hamish Low, an expert in drying and preserving Bog Oak, led the project to excavate, dry and mill the tree; a long, tricky and complex process. The Bog Oak measured more than 1.25 metres in diameter and was 13.4 metres long, though it is likely that it was only part of the original tree which may have stood some 52 metres high. It was decided that The Table for the Nation was something that could display the grandeur of this ancient tree. It was Hamish Low again who led the project to create the table, which was then expected to be unveiled at Ely Cathedral in October 2021.

In June of 2021, Philip Taylor, who was visiting Hamish on an unconnected matter, was asked if he would make a violin using Bog Oak. Philip had been making violins in the time honoured way for many years; to use this exceptionally dense, black wood for the back and sides of a violin strongly conflicted with his traditional ideas of violin making. Yet Hamish was insistent that the wood was suitable for the instrument and was keen that the unique properties of the wood be capitalised on. He described the mesmerising clarity of a guitar made from the same Bog Oak by the renown guitar maker, Gary Southwell. Hamish then explained that he was hoping that both guitar and as yet unmade violin would be played at the unveiling of the Table For the Nation at Ely Cathedral.

Philip accepted the commission, although he had serious misgivings. ‘I wondered what I was letting myself in for,’ he confesses, ‘I couldn’t believe wood that had been asleep for 5000 years would sound very lively.’

A month later, a specially selected piece of Bog Oak arrived from Hamish. ‘There were so many unknowns that I was keen to get started and find out what I was dealing with,’ Philip says, ‘So I dropped everything and concentrated on the Bog Oak.’

He discovered that the wood cut well but not as cleanly as maple. It also required more frequent sharpening of tools, but he soon had reason to be optimistic, ‘When I started to hollow out the back,’ he explains, ‘I could tell early on there was a voice ready to come out. I was a bit concerned that the violin might be too loud and so I left the back thicker than usual to compensate, knowing I could always adjust later.’ No adjustment subsequently proved necessary.

Watch: Listen to the Bog Oak violin - the world’s oldest violin?

Read: Ask the Experts: selecting the right tonewood

Read: Violin crafted entirely from wood of indigenous African trees

Philip had pegs made from the wood cut from the C-bouts. ‘I was mindful of how valuable the wood was, so I contacted my usual peg maker. He made it clear that he thought Bog Oak was entirely unsuitable for musical instruments, but finally agreed to make the pegs.

‘The problem that occupied me most during the making was how to finish the violin,’ Philip recalls. ‘I thought about this for weeks while I was making it. I don’t normally make a violin that is black and white. In the end, I used only clear varnish.’

Any assumptions that the finished instrument would sound dull, be lazy and unresponsive were shattered when it was first played. ‘It proved to be the opposite of all the things you might think an instrument made with this ancient wood would sound like,’ Philip says, ‘I was amazed when it came to life. It was a moment of joy and of relief. Everyone who plays it comments on its rich voice and clarity of tone.’

When asked about how he feels about using non-traditional woods in the future, Philip admits that the experience of making the Bog Oak violin has changed his attitudes, ‘I am still very much a traditionalist at heart, but we have to be realistic. It was a privilege to work with Bog Oak and to create the only violin of its type in the world, but it also opened my eyes to the possibility that as our traditional materials become scarcer, there could be other woods out there that we could be using to make beautiful musical instruments with.’

There is an opportunity to see and hear the Bog Oak violin at a concert given by the Blythe Quartet on 29 July in St Peters Church Guestwick, Norfolk NR20 5QJ. Further information from thebogoakviolin@gmail.com

A special thank you to Hamish Low for all the technical detail and support. Further information about the Fenland Bog Oak and The Table for the Nation at www.thefenlandblackoakproject.co.uk

Watch: Listen to the Bog Oak violin - the world’s oldest violin?

Read: In Focus: An 1824 violin by Nicolas Lupot

Read: Making Matters: Choosing the right wood

Read more lutherie articles here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stinged instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

Best of 2023: The Strad’s Twelve Days of Lutherie

- 1

- 2

Currently reading

Currently readingThe world’s first and only Bog Oak violin (as far as we know)

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

No comments yet