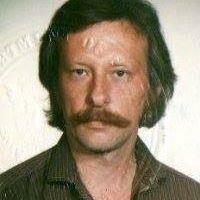

The eminent American bowmaker, master copyist and restorer has died, aged 69

Paul Martin Siefried - one of the world’s foremost bowmakers and a founder member of the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers - has died. He was 69.

Born in January 1950 and raised in Southern California, Siefried grew up in an artistic household: his mother was an amateur pianist and his father was a painter, designer and art teacher, who liked to collect fine paintings and furniture. The house was always well supplied with drawing materials, and, together with his sisters, the young Siefried liked to make use of them.

Academically though, his progress was erratic. Seeing no need to do homework between exams, he went through 12 years of schooling without once handing any in, and consequently achieved average results. After leaving school he intermittently attended an art institute and at the age of seventeen he left home, becoming an order clerk at a large music house in San Francisco.

Tiring of this, Siefried found work with a leather goods manufacturer, where he quickly learnt how to design and make objects such as gun holsters for the police, and camera case straps. ‘If you have good hands and a good eye you can make almost anything,’ he later said. But the monotony of factory life eventually led him to branch out on his own, selling his own leather creations.

- Read: Influential Italian luthier Renato Scrollavezza has died

- Read: Postcard from the inaugural Australian Luthier & Archetier Congress

- Watch: Amateur luthier’s decade-long project to make violins for his 10 grandchildren

It made him a comfortable income, but still he craved a more artistic vocation. So when he made an amazing discovery - namely that some violins were handmade - he decided that this would be it. At twenty he applied to enter the violin making school at Mittenwald. When he was rejected, a professional violinist friend approached the violin shop she patronised and requested an interview for Siefried. Eventually the proprietor - a Mr MonDragon - agreed to look at one of Paul’s handbags. He later said: ’I took one look at the handbag and could not help noticing the design, choice of material and meticulous detail of workmanship. ’I told myself that if he can make that, he can make a fiddle.’ The next week Siefried became an apprentice at Cremona Violin Makers & Dealers.

For a while, he swept floors and cleaned up the work areas. But he was also taught how to take apart, clean, polish and rehair a bow. It planted a seed; by the end of the second year Siefried knew that his heart was in bow making. He resigned and moved to a small community where he immersed himself in intense study and experimentation with bow making.

He also caught the attention of Hans Weisshaar - a maker whose seminars he had attended, and whom he greatly admired. When Weisshaar heard that Siefried was no longer employed he invited him to join his atelier in Los Angeles. It was there that Siefried was led to understand matters of style and taste, and to comprehend the nuances of elegant bow making. It was there too, that he had the opportunity to study the bows of great masters. ‘It was an absolutely humbling experience for me,’ Siefried said. ‘I didn’t make a bow for two years. I listened and just kept my mouth shut.’

In 1978 he entered an international competition in La Joya, California, sponsored by the Violin Society of America. Discovering that he was ‘a voracious competitor’, he threw himself into the task of crafting matching bows to enter in all four categories: violin, viola, cello and bass.

To his surprise, Siefried won three gold medals and one silver - then repeated the feat two years later. By the third competition, held in 1982, he was invited to become a judge.

After 10 years with Weisshaar, he opened his own shop in Los Angeles. It flourished, but he resented how little time he had for making bows himself. So in 1991, he moved with his wife and two children to Port Townsend, a place he called ‘mecca’. He set up shop in his backyard, making and restoring bows on his own schedule and serving as a coach to emerging bow makers in the area.

‘I have an open shop policy,’ he said. ‘I have zero secrets from everybody. I’m willing to help them out.’

One of the few living bowmakers to be featured on a cover of The Strad (in July 1985), he was much admired for his products, which were in the genre of Peccatte and Maire, but with the vibrancy, sensitivity and resilience of bows by Tourte and Voirin. He was also known as a master copyist and restorer - his development in these areas guided by Weisshaar, who would hand him an ‘impossible’ repair and tell him to ‘fix it.’

MonDragon once described seeing a beautiful Maire bow in Weisshaar’s shop: the ebony frog was decorated with intricately inlaid floral designs of gold and mother or pearl. He thought it was original and it was not until months later that he found out the frog was the work of Siefried.

But despite his commitment to his craft, Siefried still devoted much energy to his family and friends. ‘As you all know, my father was well loved by many people all over the world,’ wrote his son, Nik Siefried on social media last week. Self-taught and unconventional though he was, Siefried will be remembered as a heavyweight among the world’s bow makers.

No comments yet