We will never truly know what this music sounded like, argues cellist Jeffrey Solow

Many wonderful players are pulled off track by thinking that it is both possible and desirable to play older music in the way it was played during a composer’s lifetime. But if the music dates from before the time of recordings, we cannot know what it really sounded like in performance unless someone invents a time machine. Historical research has revealed new ways of understanding and playing such music but it remains impossible to know how composers liked or wanted their music to sound. Neither can we be sure of what they would have liked and wanted if they had known what players can do now and how instruments have evolved.

There is one thing that we can be sure of, though: above all, composers and performers – today and in the past – want to communicate on an emotional level with their audience.

‘One must play from the soul, not like a trained bird!’

‘Since a musician cannot move others unless he himself is moved, he must of necessity feel all of the affects that he hopes to arouse in his listeners.’

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments)

‘I know well that music is made to speak to the heart of man, and this is what I try to do if I can; music without feelings and passions is meaningless and consequently the composer achieves nothing without the performers.’

Luigi Boccherini (Germaine de Rothschild Luigi Boccherini; His Life and Work)

Since the advent of the period performance movement, we have grown accustomed to historically informed performance, but this does not mean that what is represented as historical is in fact so.

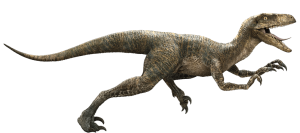

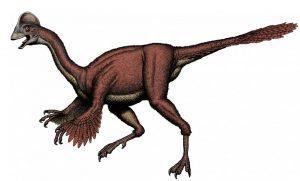

Take a non-musical example. Through modern technology and new discoveries we undoubtedly know more now about how dinosaurs looked than we did a hundred years ago (for example, not ‘tail draggers’). The fabulous special effects of Jurassic Park convincingly persuaded us that that was how they really looked. Yet newer evidence shows that even these realistic reconstructions are wrong – raptors had feathers (a recently discovered specimen was dubbed the ‘Chicken from Hell’).

Jurassic Park Velociraptor

'Chicken From Hell'

Even if it were possible to recreate accurate original performance practices, it is likely that they would sound so far removed from today’s norm that audiences would focus on the style and miss the essence of the music. Attempted re-creations are fine in an intellectual and abstract sense, but without recordings (or that time machine) we can never know if they are correct – and they miss the point artistically.

In his book A Century of Recorded Music Timothy Day articulated this idea well: ‘A performer cannot continue to cultivate the same style in all of its details – even if this were humanly possible – and expect the effect of his interpretation to remain the same, to expect that the same musical gestures will convey the same significances to new audiences […] The same musical gestures, the same kind of emphases, will convey different meanings, will have a different effect, will be judged more or less convincing or successful, at different times.’

Consider vibrato. Initially employed as an ornament, it has now become a vital ingredient of musical communication. Abandoning it diminishes interpretive complexity and richness, and who should want that? (Besides, Leopold Mozart’s oft-quoted comment, ‘There are performers who tremble consistently on each note as if they had the palsy,’ means that there were violinists in his day who applied vibrato continuously.)

I do not disregard what can be learnt from studying historical instruments and sources, but we should not sacrifice music on the altar of style. No matter how much was written in the pre-recording era about performance style, or how many scholarly studies and opinions have been presented since, words are not sounds. (And as for period instruments, Richard Taruskin said it perfectly: ‘Instruments do not make music, people do.’) Interpretive choices should never be made ideologically but instead for musical and communicative reasons. Character, rhythm, timing, tone, phrasing, tempo, nuance, energy and flow: these are the crucial elements of a performance and they cannot be surrendered to historians or musicologists. The responsibility of every performer is to study what is known about past composers and players, look carefully at what the composer wrote, and let the music tell you how it wants to sound and to the best of your ability play it that way.

No comments yet