Excerpt from Desmond Cecil’s newly published memoir: ‘The Wandering Civil Servant of Stradivarius’

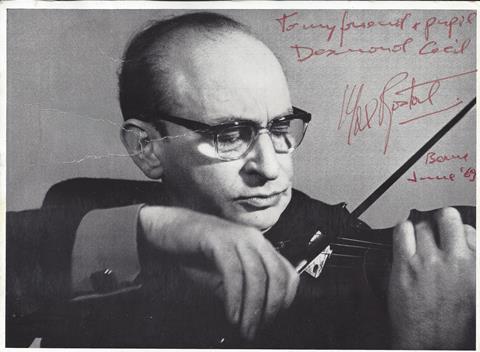

The former diplomat Desmond Cecil CMG has recently published his memoir, The Wandering Civil Servant of Stradivarius, in which he details his time as a professional violinist at the start of his career. In 1965 he moved to Switzerland for full-time violin study with the illustrious Max Rostal, staying there for five years playing with and leading various Swiss chamber orchestras. In the following excerpt from the memoir, Cecil recalls his time with Rostal and some of the wisdom he learnt there:

In 1965, we moved to Switzerland, initially for Rostal’s annual summer course in Adelboden in the Bernese Oberland. Then in October 1965 we moved permanently to Berne. Despite his years in London, Rostal remained very formal and Germanic and was addressed by his students as ‘Herr Professor’, although towards the end of my studies he, quite unexpectedly, instructed me that I was now allowed to address him as ‘Max’ and to use the ‘Du’ form. Underneath the austere exterior he was a kindly man, and in time he became a good personal friend.

He had a reputation, no doubt well deserved, for being tight-fisted with money. However, once when I was performing at his masterclass in Adelboden, he said that if I re-played a certain passage better, he would give me 5 centimes. Apparently I did play it better, because he then handed over the 5 centimes coin, much to the amusement of the audience. I still treasure that coin, which is safely preserved in my violin case to this day.

Although I came prepared with the usual ‘masterworks’, violin lessons with Rostal began, as many fine teachers do with their pupils, by going back to basics – posture, bow hold, left-hand position, and then slow bow strokes moving to Flesch-school scales and arpeggios, etc. After some weeks we moved on the Etudes, Kreutzer, Rode, Dont and others – familiar to all young violinists. These provided the inevitable hurdles, some of which were overcome quickly, others much later. I remember Rode’s second study in octaves, which, unlike some other double-stoppings, I could manage relatively easily. ‘Thank God for that,’ exclaimed Max.

Read: The 1724 ‘Cecil’ Stradivarius – a masterpiece unseen and unheard

Buy: Antonio Stradivari ‘Cecil’ violin 1724 poster

Read: Book review: Bow to Baton: A Leader’s Life

Max held his violin well to the left, which suited me with my long arms. He had his chinrest on the left side of the tailpiece, which I was never happy with – years later I moved to a central chinrest and have been happy ever since. He used a soft shoulder pad, and was relaxed about what kind of shoulder rest his pupils used. Like many others, I experimented with the various models, Resonans, Menuhin, Wolf and other designs, which all claimed to be the perfect solution. However, I never felt at ease with any of these, and later reverted to playing with no shoulder rest, simply putting the violin on my collarbone and holding it horizontally with the left hand – as I can recall the renowned Hungarian violinist and teacher Tibor Varga demonstrating very clearly at a Dartington Hall summer masterclass.

Changing position needed some thumb flexibility, which Max was a master of, and the slight ridge at the back of the chinrest prevented the violin from slipping away when changing down. The left-hand fingers were supported by the left thumb, thereby enhancing inherent vibrato, and taking away the pressure between shoulder and chin. Most young violinists from the conservatoires are encouraged to use shoulder rests, and one can see the negative results in shoulder tension and visible chin sores (which fortunately I do not suffer from, despite intensive playing). Once I had overcome the initial dynamics of playing without a shoulder rest, I never looked back. I always felt that the violin sounded more natural and free without a mechanical clamp at the back – as Jascha Heifetz, Yehudi Menuhin (once he had dispensed with his own designed shoulder rest) and many other greats, including Anne-Sophie Mutter today, have demonstrated. The only problem is that they all play much better than I do!

As the months went by, I gradually decided that, although I had benefited enormously from my five years in Berne – the extraordinary musical and technical lessons that I had learnt from Max, playing and teaching as a professional – I was not going to achieve my initial ambition of becoming a top soloist.

Happily the personal friendship continued after I had stopped studying with him, and we would meet from time to time. When I was at the British Embassy in Bonn a few years later, Max was still teaching nearby at the Cologne Hochschule. He would sometimes ask me to join him in Cologne to play string quartets with him and friends, but made it quite clear that I would play second violin!

After Rostal’s death in 1991 a group of us former pupils of his now in the UK gathered together in a chamber orchestra to give a public London concert in his memory.

The Wandering Civil Servant of Stradivarius is published by Quartet Books and available at Amazon and Waterstones. The author has decided to donate all royalties to arts charities, especially to support young musicians, who need all the help that they can get nowadays.

No comments yet