At the 13th Banff International String Quartet Competition ten young ensembles, their members all under 35 years of age, rose to the challenge of performing a vast amount of wide-ranging repertoire, reports Laurinel Owen

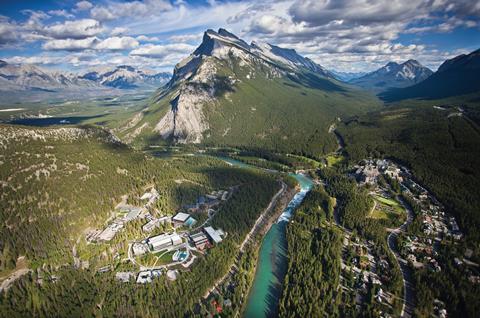

First of all, let me say that I live in the US and naively, like many Americans, thought of Canadians as being pretty much like us – only nicer. Indeed, these folks are personable and friendly, but witnessing the government’s support of the arts was an eye-opener. The activities surrounding the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity since its inception in 1933 have positioned the organisation as a cutting-edge, world-class institution. Situated in the Banff National Park in the Canadian Rockies, the centre’s environment of natural beauty is unparalleled. I thought I’d stepped into a National Geographic magazine.

Thirty-seven string quartets entered this year’s competition, and after the initial application stages, which included a requirement for video recordings to be submitted online, the ten ensembles selected to continue to the live stages (26 August to 1 September) were invited to Banff with all expenses paid, and participated in four gruelling and intense rounds before the finals. Fortunately, the organisation of the event was extraordinary.

‘Our team focuses on what we can do to make it possible for the groups to perform at their best,’ said competition director Barry Shiffman. ‘We remove financial hurdles, and don’t select the three finalists until the night before the final round. The seven that are eliminated are celebrated honestly, with each awarded a $4,000 career grant. We audio- and video-record all performances in high definition and at a professional level, then provide everyone with a copy. And I can assure you – they need it!’

The first four rounds were the Recital Round, which included a quartet by Haydn and a work written after 1905; the Romantic Round, comprising a quartet from the Romantic repertoire; the Canadian Commission Round, featuring Finland-based Canadian composer Matthew Whittall’s String Quartet no.2, Bright Ferment; and the ‘Schubertplus’ Round, which was to be a programme no longer than half an hour and featuring the first movement of a late Schubert quartet plus additional repertoire of the contestants’ choice. While juggling all this repertoire, the players also had to keep a complete Beethoven quartet in their fingers in anticipation of proceeding to the finals. All concerts were performed in the (almost full) Eric Harvie Theatre to an audience of dedicated and serious music lovers, several hundred of whom had come from Canada, the US and abroad to spend the week absorbing the dozens of hours of concerts and lectures.

There were seven adjudicators: violinists Martin Beaver, David Harrington and Philip Setzer, violists Gillian Ansell and Nobuko Imai, and cellists Adrian Fung and Ursula Smith. When I spoke with Fung (also an educator and arts executive) about the judging process, he said: ‘This is a unique experience for me because the audience is so knowledgeable, astute and opinionated. They seem to root in favour of repertoire. But our role is clear: of course, intonation and style, though more compelling for me is the “story” and beauty of each performance. Composers don’t want you to “play the ink”, but to find the rhymes and rhetoric – the magic in the music. The quartet that separates itself looks past the text. Some have perfect technique, but we need to be led by the heart. I try to unpack a musical voice and advocate for the performance that expresses solace, power, vitality. A voice that can change the world.’

Emerson Quartet violinist Setzer was also happy to elaborate: ‘Barry Shiffman chose jury members who know the quartet repertoire, but are diverse in age, nationality, variety of outlooks and their approach to music. The members of this panel have a tremendous respect for one another. We are kind and committed to doing the “right thing”. Until the completion of the first four rounds, we do not discuss the performances.

‘It is very difficult to assign a score from 1 to 20 to a performance. We each hear different qualities. How do we make that a number? We each need to have a strong opinion, then we allocate a number and sign the form, so that we select a strong winner. This can create a compromise situation, as is the case in many competitions, when there is a group with a very strong personality which some like and others don’t. The results could be surprising. That is why a large jury is good.’

The audience’s programme stated that the jury was asked to judge on ‘a unique artistic voice and presence’. Setzer commented: ‘Unique for me means something has to grab me. Am I drawn to the performers? Is there charisma, great technique, chemistry, excitement? Am I moved? Of course, if they are not playing at a high technical level, I’m distracted and can’t be moved.

I was struck by the obvious need for the groups to pace themselves through the week. Not only was there a huge amount of music to perform, but the acoustics of the hall itself were a challenge – there was no hiding. If the quartet sounded good, it was good.

During the first six days we heard the following quartets: the Agate Quartet (France), the Callisto (US), the Eliot (Canada/Germany/Russia), the Elmire (France), the Marmen (UK), the Omer (US), the Ruisi (UK), the Ulysses (Canada/US/Taiwan), the Vera (Spain/US) and the Viano (Canada/US). After jury deliberation on Saturday evening, the three finalists were announced: the Callisto, which had won America’s Fischoff National Chamber Music Competition in 2018; the Marmen, which had won the top prize at the 2019 Bordeaux International String Quartet Competition; and the Viano, which has since taken up residency at the Colburn Conservatory of Music, Los Angeles.

On the final day, Sunday, we listened to Beethoven. The Callisto’s op.59 no.2 was muscular with expressive contrasts between power, warmth and tenderness, though the last movement was so very fast that their instruments didn’t always respond.

The Marmen’s op.131 was conversational, presenting the four instruments as clearly distinctive voices which nevertheless came together as a united whole. Explosions were followed by pale, flat fragments that blossomed into sweetness. The audience cheered and hooted, and half the hall stood after the performance.

The Viano’s op.59 no.3 was energetic without harshness, rhythmic yet elastic, warm and lush, then crisp and articulate. The last movement was the fastest I’d ever heard it.

Then we waited for more than two hours for the results. Setzer had spoken of surprise, but the results were unprecedented for this competition: first prize was a tie between the Marmen and Viano quartets. This meant that the usual total prize value – more than $300,000 worth of cash, tours, recordings and residencies – had to be distributed differently compared with previous years.

Afterwards, at the winners’ press conference, the Marmen Quartet’s cellist, Steffan Morris, admitted: ‘I’m finished with competitions. That’s it! I’m done.’

No comments yet