The US cello soloist and recording artist on following her instinct on a path to true musical fulfilment

When I was young I would often fall into the trap of trying to conform to an image of what I thought success looked like: a concert cellist touring the world. I was still lost in that stubborn illusion when I was living in the UK, studying with Jacqueline du Pré and teaching at music college while bringing up my son as a single parent. It resulted in a major health crash that led me to move back to the US. Following a path that is not one’s own is dangerous and can lead to burnout. Each time I went on tour it would make me sick; I was trying to swim in a river that was not my own. In recording, without the added stress of travel, I found my own river and its current embraced and carried me. Through difficult experiences I learnt to trust my inner guidance and the little voice that lovingly keeps me on the right path, as well as to distinguish between that and the deceptive ego that can lead one badly astray.

I think music competitions will cease to exist one day, if humans are able to transcend their present level of consciousness. They are one manifestation of the insidious way ego creeps into art, and they seem to me to be anti-art, anti-artist and intrinsically violent. For someone to win, someone else has to lose, creating so much needless pain. On the other hand, one could use a competition as a kind of powerful spiritual practice. Is it possible to participate in a competition in a state of equanimity, regardless of the outcome, concentrating only on the music? It certainly wasn’t for me, 40 years ago, when I was playing in competitions and experiencing both winning and losing. If I could, I’d tell my younger self to embrace the spirit of the music with no attachment to the results – that would mean I’d succeeded in a way that was more meaningful than the outcome of any competition could ever be.

Read: Rohan de Saram: Life Lessons

Read: Nobuko Imai: Life Lessons

Read: Guy Johnston: Life Lessons

The memory of my father playing Bach on the pipe organ is far more vivid and visceral than my early recollections of actual cello lessons. As I lay in bed at night as a young child I could hear him – an electrical engineer by profession – playing on the instrument he had painstakingly built in our basement, with pipes shipped over from Germany. The haunting, distant sound of Bach on the organ wafting through the house in the nocturnal solitude was my first tutor. Nature was another and I think its stillness has profound things to teach us. It brings us closer to true artistic inspiration than dusty book learning ever can. I spent most of my childhood wandering in the woods instead of practising, but maybe connecting with that rich and spacious stillness was its own kind of education.

-

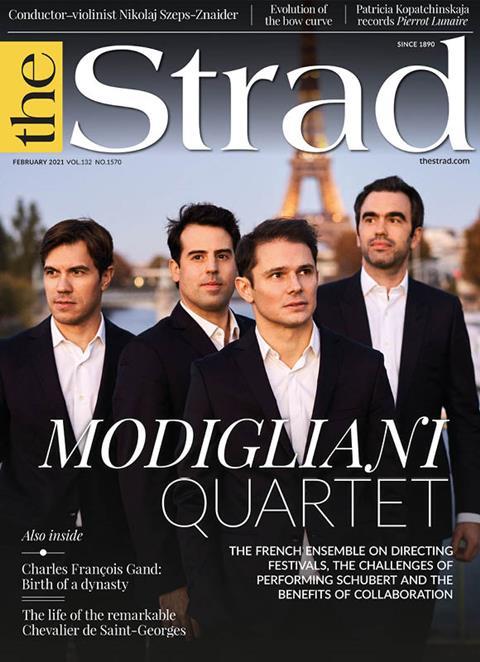

This article was published in the February 2021 Modigliani Quartet issue

The French ensemble on directing festivals, the challenges of performing Schubert and the benefits of collaboration. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French ensemble the Modigliani Quartet

- Charles-François Gand: birth of a dynasty

- Conductor-violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider

- Patricia Kopatchinskaja records Pierrot Lunaire

- Evolution of the bow curve

- The life of the remarkable Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Read more playing content here

No comments yet