Christopher Nupen remembers his time documenting Jacqueline du Pré at the height of her musical career, in this extract from the October 2021 issue

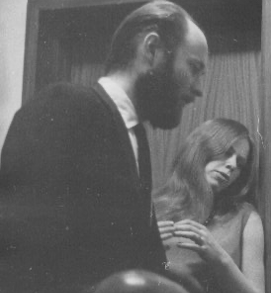

Photo: Allegro Films

Nupen and du Pré in around 1968

The following extract is from The Strad’s October 2021 issue feature ‘Golden Girl: Nupen and du Pré’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The October 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

It is the job of films, radio, television and the press to keep Jackie’s spirit alive in the world, and they are doing well with this so far. Way back in the beginning, Huw Wheldon, for me the best man on the production side that the BBC has ever had, said to me, ‘Nupen, you have found yourself a star. Use her. Your less courageous colleagues will warn you of the dangers of overuse. Heed them not. You will find that the dangers of overuse come a long way further down the line than your less courageous colleagues fear.’ He was right, thank the heavens: he often saw further than the rest of us. We made nine productions with Jackie before multiple sclerosis overtook us.

Huge surprise followed the television broadcast of our first film together, Jacqueline (1967), featuring a complete performance of the Elgar Concerto with Daniel Barenboim (whom she had recently married). We had shot the Elgar differently from the way that music was shot in those days, and that had an impact on the public response. As a result, EMI twice ran out of stock of the 1965 Barbirolli Elgar recording. This was totally unexpected and they had to reprint shellac discs in a hurry.

The next significant event also happened around this time: Jackie and her husband’s first encounter with violinist Pinchas Zukerman in New York. They were so impressed that they invited him to visit them in London, and very soon there was a new trio in the world. Unusually, Jackie could find no adequate words to describe the beauty of Pinchas’s playing. All she could say was, ‘Kitty, just wait till you hear him’ (Kitty was her nickname for me).

The opportunity for me to hear Pinchas with Jackie came soon after, at Oxford Town Hall, playing Beethoven’s ‘Ghost’ Trio. As always with music, Jackie was right: I had never heard two stringed instruments resonate together in quite that way. It was the deepest musical experience I had had up to that time.

There was another unexpected, spontaneous confirmation of the power of the ‘Ghost’. In 1970 I filmed their performance of the work at St John’s Smith Square, London. At the end of a public screening at the Louvre in Paris, a woman with a most impressive voice (perhaps an opera singer?) stood up and announced, loud and clear for all to hear, ‘Remarquable, c’était remarquable!’ It was a great moment.

I have no doubt that making nine productions with Jackie taught me something that added a visual quality to all my subsequent productions. That is highly unusual for specific reasons: the first two, of course, are her supernatural talent and her unforgettable charisma; but the thing that made the biggest difference to her relationship with the world around her and the ever-growing public that remembers her so lovingly was the invention of the first silent, or nearly silent, 16mm film cameras. We took cameras to places with Jackie and persuaded her to do things that had not been done in music films before. She created a different atmosphere, a different world. Jackie’s pizzicato on the train won the hearts of a new audience in many parts of the world – the camera loved her.

Read: Nupen and du Pré: Golden girl

Read: Group Therapy: Jacqueline du Pré

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

-

This article was published in the October 2021 Janine Jansen issue

The Dutch violinist performs on twelve of the world’s finest Stradivaris for a new recording and documentary. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Janine Jansen’s Stradivari recording project

- The on-screen legacy of Jacqueline du Pré

- Exploring historic varnish recipes

- Juilliard’s new Chinese campus

- Duos from Kopatchinskaja and Gabetta

- The Strad Calendar 2022

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet