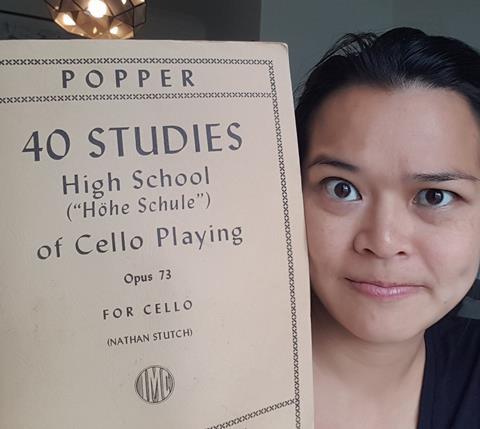

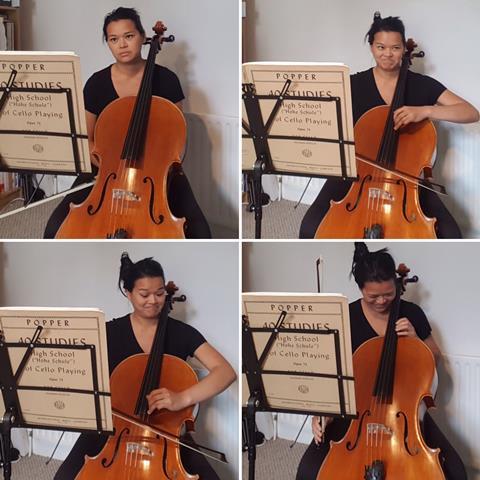

The enjoyability and longevity of Popper studies lie in the small gains that gradually accumulate to a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment, writes cellist and online editor Davina Shum

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Mention ‘Popper studies’ to any cellist playing at an advanced level – whether it’s someone studying at music college, an active performer or one of those prodigies you see on YouTube through knitted fingers – and you will most likely be met with mixed opinions and emotion. There’s despair, pain, frustration, but also satisfaction, addiction and obsession.

For those who are unfamiliar with David Popper, he was a virtuoso Bohemian cellist, born in Prague in 1843. He wrote a wealth of repertoire that showcased and extended the cello’s virtuosic capabilities. Many works are still played today, occupying that space in cello repertoire of ‘dizzyingly fast concert piece’, often performed as encores: the ones that send a giggly ripple of appreciation through the audience. Never mind that you’ve just hauled your way through the Elgar or Dvořák concerto, why not end your performance on a high – quite literally, as a lot of Popper’s pieces feature passages in the stratospheric register of the instrument. As I write this, I have the Tokyo Olympics on my TV in the background – it’s like doing your entire gymnastics routine, winning gold, and then saying, ‘Well, I fancy doing all the hard bits of that again in two minutes’.

Popper is perhaps most well-known for his magnum opus: The High School of Cello Playing comprising of 40 studies. High indeed – in the words of Rhonda Rider, chair of chamber music at Berklee Conservatory in Boston: ‘You have to know the fingerboard both up and down and across the strings’ to play them well. Cellists often moan about playing up high. Who can blame us? We spend so much time enjoying juicy basslines that high stuff is a little out of our comfort zone. In Popper’s studies, you’ll find yourself in unexpected terrain many times – for example, up past harmonic thumb position on the C string. You might even question why Popper wrote certain fingerings up high when you could play exactly the same notes down low in a more comfortable position. But I suppose that’s not the point, is it? One of the aims of these studies, and indeed any form of art is to push your limits and extend your capabilities in order to achieve versatility and freedom in your musical expression. It’s sort of Popper’s way of saying, ‘Look, I know I don’t have to do it this way. But I can!’ Personally, my cello is riddled with plenty of wolf notes up high on the C string (not that I’m blaming my tools in any way at all) so next time I want to replicate the colour and timbre of Chewbacca moaning when Han Solo gets frozen in carbonite at the end of The Empire Strikes Back, perhaps I will consider playing in that register.

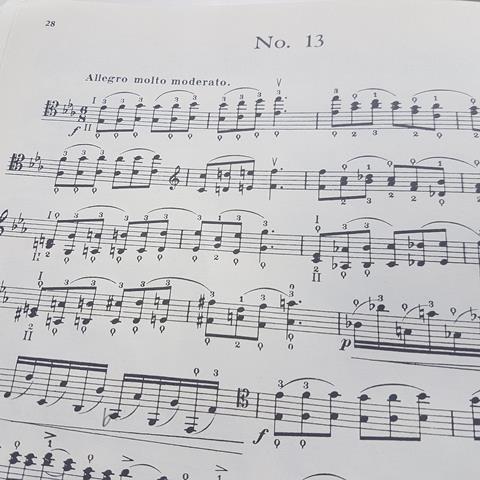

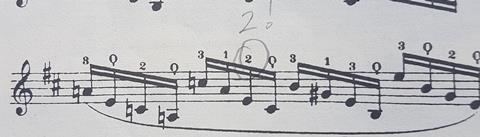

And that’s only if you happen to be playing one of the studies where you get to play one note at a time. Probably one of the most notorious uses of Popper studies is to develop the left-hand frame to execute double stops successfully in all positions, including those implementing the thumb up in the high register. No.9 is a study of 3rds, 6ths and octaves. No.13 starts with octaves right off the bat. No.34, while beautiful and idiomatic, decides to throw some left-hand pizzicato into the mix. Not to mention the countless others that require a secure thumb-to-third-finger frame to facilitate all the notes in between (for example, the infamous no.33). These studies require careful, disciplined practice, often isolating one note at a time, feeling the connections of the shifts in position changes and consolidating finger patterns and hand shapes. These studies also require tolerant family members/housemates/neighbours that will continue to be near you even while you re-create noises that Popper definitely did not intend for you to make, both musical and non-musical, including groans of exasperation as your rate of practice outstrips the rate at which your thumb callous can replenish. It’ll be quite some time before I ask Google ‘How to remove blood from an ebony fingerboard’ again.

If that weren’t enough, it’s as if Popper taps you on the shoulder and says, ‘Great! Now make all of that smooth and seamless. Thanks. Bye’. A solid left-hand framework is only as good as the work you put into the bow arm. You can have the most beautifully in tune octaves, but they’ll sound rubbish if you can only approach them with force resembling a hydraulic press. You might have a fluid, effortless facility in the left hand but if you don’t know how to adjust minute details of your bow contact point in various positions, you’ll end up with a detaché that sounds fluffée or a legato slur that would make even the most hardened sailors seasick.

Again, it seems like I’m moaning, but something that Popper studies bring with them are a great sense of satisfaction once you get stuck in. The victories may be small – for example, ‘Today I didn’t fall off my fingerboard!’ or ‘I only screamed once’ – but victories nonetheless, which gradually accumulate to a series of wins that lead to accomplishment. Like many successes, the ability to play Popper studies is a slow burn, requiring disciplined practice and plenty of patience. I think it’s best to focus on the little victories – because as any artist knows, you never fully master a piece. In the words of the great cellist Pablo Casals when asked why he still practised every day at the age of 67, he replied, ‘Because I feel I’m making daily progress’. That is the attitude we must bring to these studies – not to tick a box marking Popper studies as ‘Done’, but to learn the art of self-evaluation, physical awareness and enjoying the process. Otherwise they would’ve ended up in the bin years ago.

Prior to taking up the role of Online Editor at The Strad, Davina Shum enjoyed a busy freelance career as a cellist, teacher and broadcaster. She runs her own podcast ‘As It Comes: Life from a musician’s point of view’ and still occasionally finds the time to marvel at the works of David Popper.

Read: ‘I value them as supremely sharp tools’ - Colin Carr on Popper studies

Read: Popper cello etudes: Rites of passage

Watch: Anastasia Kobekina and Nicolas Baldeyrou perform Popper’s Dance of the Elves

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet