Oskar Falta examines Soviet cellist Daniil Shafran’s unique left-hand technique and vibrato in this extract from the September 2021 issue

The following extract is from The Strad’s September 2021 issue feature ’The Unsung Hero’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The September 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

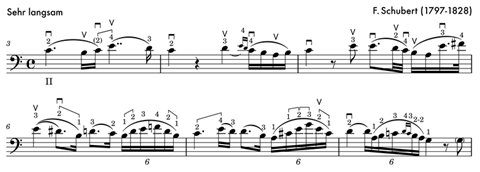

Shafran’s left-hand technique was anything but conventional. Early on, he trained his hand to produce equal sound with all five fingers interchangeably. This approach built remarkable strength in his fourth finger and thumb, paving the way for a personalised fingering system unlike any other. Shafran frequently employed the fourth finger beyond the half-string harmonic and the thumb in lower positions – not only in fast technical passagework but also in melodic passages with vibrato. While still a student, Shafran once asked professor Shtrimer if he might also play vibrato with the thumb. He replied: ‘Do everything how you want, how you can, and how you think it needs to be done.’ And Shafran did. Isserlis recalls telling Shafran at the dinner after the 1995 Wigmore Hall recital that cellists were going to wake up the next day with an extra finger (in other words, their thumb). Shafran laughed and responded: ‘God gave us five fingers. Why shouldn’t we use them all?’ Shafran likewise reflected this skill in double-stopped octaves – besides fingering them in the usual manner with the thumb and the third finger, Shafran played octaves with equal ease using the first and fourth fingers across the entire range of the cello. Thanks to the complete command of each finger, Shafran became independent of prevalent fingering solutions, which he thought limited expression. Moreover, this skill allowed Shafran to play his own arrangements, like the Shostakovich Viola Sonata, with little compromise. Shafran’s use of the fourth finger and thumb outside the limits set by tradition expanded his fingering options and, furthermore, made it possible to apply extended stretches.

Partly because of Shafran’s broad handspan and the shorter stop length of his cello, he could replace a good number of shifts with a stretch, moving around the fingerboard in an almost violinistic manner. Therefore, he was free to keep audible shifting only for expressive purposes (rather than as a means of changing from one position to another) and avoid it altogether in places where he considered it in poor taste. Occasionally, he employed a unique sort of portamento (both ascending and descending), dragging the finger through all intermediate chromatic steps before reaching the destination note.

The most striking (and most frequently imitated) expressive tool used by Shafran was a vibrato that set him apart from other cellists. With his massive fingertips covering a large surface of the string, his vibrato could reach an almost electric speed. His expressive treatment of it was remarkable: non-vibrato (so-called ‘white tone’) could be followed suddenly by an intensely fast vibrato. It became his trademark, known to fans as ‘Shafranism’.

Shafran strongly believed that much as a brush stroke defines a painter, the cellist is defined by bowing technique – in terms of application of bow strokes, articulation and sound production. He preferred to play with looser bow hair and varied the slant of the stick with the help of his right-hand fingers: thus, by using less hair in the lower quarter of the bow, Shafran achieved an equal distribution of arm weight, resulting in a balanced sound throughout the bow. Shafran’s bouncing strokes had a special clarity, as if they were more spoken than sung. He controlled the bow speed and contact point with a watchmaker’s precision, developing a wide palette of dynamic nuances.

Read: Daniil Shafran: The unsung hero

Read: My Heroes: Steven Isserlis on Pablo Casals and Daniil Shafran

Read: Daniil Shafran’s practice routine

-

This article was published in the September 2021 Suzuki issue

How the intuitive teaching method has become an unparalleled success around the globe since its founding in 1945. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Suzuki teaching method

- Why conservatoires should embrace HIP

- The great antiquing debate: experts weigh in

- Violin making and AI

- Soviet cellist Daniil Shafran

- Choosing the right sized viola

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet