The son of a wealthy French plantation owner and his enslaved African mistress, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges led an extraordinary life - though his compositions remain unfairly neglected, writes Kevin MacDonald

The following are two extracts from The Strad’s February issue feature about the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The February 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

Saint-Georges was born on Christmas Day 1745 on the island of Guadeloupe, son of George Boulogne de Saint-Georges (a wealthy planter of Huguenot descent) and Anne Nanon (an enslaved chambermaid of African descent). George Boulogne had appended ‘Saint-Georges’ to his name a few years before, perhaps to imply nobility, but it was his son who was to lend the name renown. Despite being already married, and with a daughter, George managed to sustain a double relationship for nearly two decades, taking Anne Nanon to France with him twice, and ultimately abandoning both of his families in France, returning de nitively to Guadeloupe in 1764 (dying there in 1774).

It is clear that there was real affection between father and son, not least because in 1753 he deliberately took Joseph away from a life of legal racial restrictions under the Code Noir in Guadeloupe to a place of relatively greater freedom and educational opportunity in France. With the influence of a wealthy brother, well connected with the court of Louis XV, George opened doors for Joseph. These efforts were aided by the fact that Joseph was already showing a remarkable talent for both fencing and music. In 1761 he was inscribed in the Gendarmes de la Garde du Roi, an elite cavalry formation attached to the royal household. Joseph had already been enrolled in the world-leading fencing academy of Nicolas Texier de La Boëssière – who would become a sort of godfather to him – at the age of 13. In the 1760s Joseph became known as one of France’s champion fencers, a role that he was to uphold throughout his life. His rapid ascent in music ran parallel to that in athleticism.

********************************************************************************************************************

The character of the chevalier was complex: ambitious, violent, but also likeable, generous and deeply sensitive. La Boëssière wrote in his Traité de l’art des armes (1818) that ‘despite his volatile temperament he handled himself so well that it was impossible to complain about his occasional outbursts’. The Journal de Paris (17 March 1777) recounts Saint-Georges’s reaction to his colleague Leduc’s death while rehearsing the adagio from one of his friend’s symphonies at the Concert des Amateurs: ‘Moved by the expressive quality of the composition, and remembering that his friend was no more, he dropped his bow and burst into tears; his emotion communicated itself to the other artists, and the rehearsal had to be suspended.’

From the late 1770s, Saint-Georges was frequently invited to perform at Marie-Antoinette’s musical gatherings at the Petit Trianon and Salon de la Paix, Versailles. It is likely that this included playing violin accompaniment to the young queen at the keyboard. Unfortunately, his celebrity and proximity to the court would eventually play against him in the coming revolution.

-

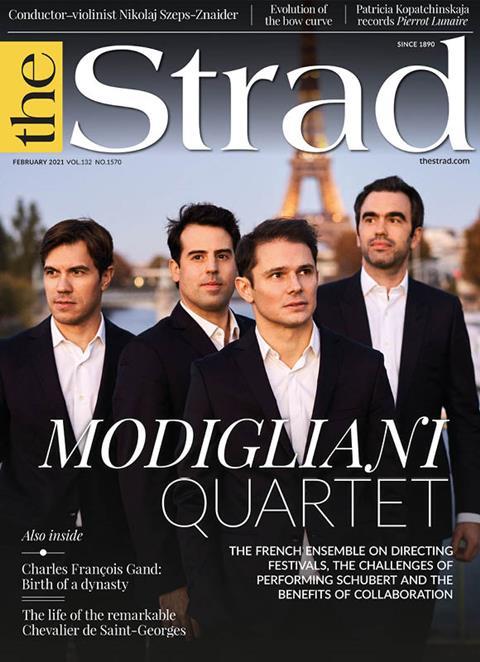

This article was published in the February 2021 Modigliani Quartet issue

The French ensemble on directing festivals, the challenges of performing Schubert and the benefits of collaboration. Explore all the articles in this issue .Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French ensemble the Modigliani Quartet

- Charles-François Gand: birth of a dynasty

- Conductor-violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider

- Patricia Kopatchinskaja records Pierrot Lunaire

- Evolution of the bow curve

- The life of the remarkable Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Read more playing content here

No comments yet