During the 19th century there was an upsurge of interest in violin playing in Britain. At its centre, writes Kevin MacDonald, was the Scottish violinist and writer William C. Honeyman – purveyor of string secrets to the masses and possible inspiration for Sherlock Holmes

The following is an excerpt from the article ‘William C. Honeyman: ‘The People’s Violin Man’ published in The Strad March 2020 issue.

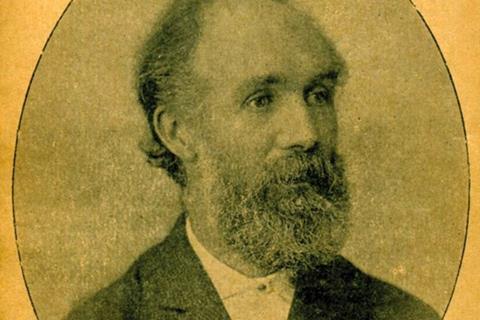

Before there was The Strad magazine, before there was Sherlock Holmes, there was William C. Honeyman (1845–1919), violinist, journalist and mystery writer. Honeyman was very much a Scottish personality: leader of the Leith Theatre orchestra and the Dundee Symphony Orchestra, columnist and sometimes editor of the Dundee-based People’s Friend magazine for 37 years (1872–1909), and author of Scottish Violin Makers: Past and Present (1899).

Importantly, prior to The Strad’s 1890 debut, his pioneering articles and violin column in The People’s Friend, as well as two initial violin how-to books (The Violin: How to Master It, 1881; The Secrets of Violin Playing, 1890), fed a hunger for information by non-professional players during the Victorian violin fever that swept across all economic classes in Britain.

- Read: William C. Honeyman: The People’s Violin Man

- Read: Was Sherlock Holmes actually meant to be any good at playing the violin?

- Read: Luthier completes ‘Sherlock’ quartet of instruments

Slightly over a century since Honeyman’s death in April 1919, it is a good time to review his contributions to the early British violin literature. Yet before I begin in earnest, a brief digression concerning Honeyman’s possible impact on the great violinist–detective Sherlock Holmes is required. A professional violinist plagued by illness, Honeyman wrote the serialised McGovan detective stories from 1873 under the pen name James McGovan, to supplement his income.

They were enormously popular, anthologised from 1878 and translated into French and German. They featured an Edinburgh detective, the recruitment of street youngsters to fight crime and an arch-villain (McCluskie as opposed to Arthur Conan Doyle’s Moriarty) at the centre of a web of operatives – all available on news-stands when Doyle was a young Edinburgh medical student. That Doyle, not a very musical man, should have chosen (in A Study in Scarlet in 1887) that Holmes be a violinist is perhaps a nod to Honeyman’s other popular writings on violins. String teacher and writer Mary Anne Alburger has even suggested that Holmes’s retirement to keep bees is a final wink, in that he truly becomes a ‘Honey-man’.

To read the full profile of William C. Honeyman, and his views on violin-playing, click here to log in or subscribe

The digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

No comments yet