Musicologist and counterpoint enthusiast Laurent Matthys makes the case for adopting a contrapuntal mindset when approaching these monumental works of solo string repertoire

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

One of the hallmarks of J.S. Bach’s music is the rich polyphonic language. Even when composing solo works for monophonic instruments, such as the violin or the cello, Bach couldn’t resist the temptation to write multi-layered music. The contrapuntal nature of the Cello Suites and the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin presents not only a major technical challenge to the performers. The executor is also faced with the intellectual task of making sense out of the implied polyphony inherent to these works. In this article, I would like to invite the performer to reflect on the underlying harmonic and polyphonic structure of these towering works. After all, an in-depth understanding of a work of music is crucial for a convincing performance.

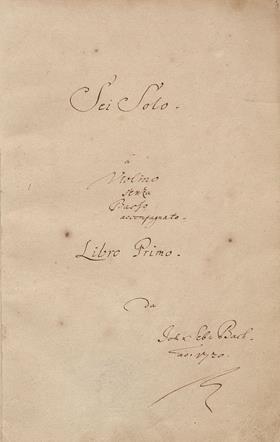

J.S. Bach’s Suites, Sonatas and Partitas were written for solo cello and solo violin respectively, without the typical baroque accompaniment of a basso continuo. This has prompted some Romantic composers and arrangers like Robert Schumann to create their own piano accompaniment, as if these pieces would need a ‘foundation’. But nothing could be further from the truth. In fact the designation ‘unaccompanied’ is a little bit misleading: the solo violin or cello doesn’t need a ‘basso accompagnato’ in order to make sense musically, it accompanies itself. When listening to these enigmatic works, one often has the impression of two or more melodic lines playing simultaneously. Yet, most of the time, the polyphonic lines are not entirely written out on paper. It is fascinating to see how Bach manages to imply a two- or three-part contrapuntal texture by using just a couple of compositional techniques. The greater the constraints, the more inventive he becomes, so it seems. He gives the performer and the listener just enough data to make sense out of the music. Some interesting research has already been done regarding the harmonic structure of these works. In this respect, the analyses of Prof. Joel Lester and Prof. Allen Winold are excellent and inspiring. Based on this research, I challenged myself to delve deeper into Bach’s implied polyphony, with the aim of connecting the vertical harmonic elements and the horizontal lines into a real contrapuntal tapestry.

The solo violin or cello doesn’t need a ‘basso accompagnato’ in order to make sense musically, it accompanies itself

In his works for solo cello and violin, J.S. Bach reveals himself as the master of compound melody. This compositional technique, where a single melodic line on paper sounds as two or more simultaneous voices, is an important device to suggest polyphony, especially when used for monophonic instruments with limited polyphonic capabilities. Compound melody - also known as unfolding - is realised by alternating back and forth between (a group of) notes of different implied melodies. This evocation of polyphony is all the more effective when using bigger intervals. A clear example of this technique can be found in Bach’s famous Prelude from the first Cello Suite (ex.1). Modern ears interpret the opening arpeggios as a simple progression of vertical chords but there is a lot more going on in the music. Bach manages to imply three simultaneous horizontal melodic lines by writing only one. In this type of music, melody, harmony and rhythm are united: as in the Gestalt psychology, the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts.

Imitation - the echoing of previous musical motives- is frequently used in contrapuntal music. This kind of dialogue between two or more voices creates stratification. It is abundant in Bach’s music language. Imitation is very clear in his canons and fugues but also omnipresent in the non-fugal pieces. A fine example can be found in the imitative dialogue between the two lower voices (blue and green) created by the three-part compound melody in the Allegro of the second Violin Sonata (ex.2).

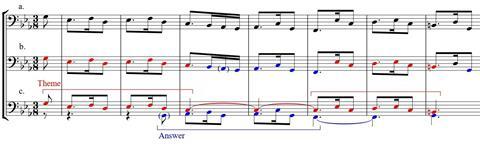

Bach uses imitation in many forms and on different levels. In my opinion, the opening of the Gigue from the fifth Cello Suite e.g. contains a very subtle and hidden form of imitative counterpoint, suggesting a theme with answer (ex.3).

When performing multiple stops on violin or cello, two, three or four strings are played simultaneously. One must however take into account that, in general, the bridge of baroque string instruments was flatter, making it possible to play multiple stops in a more fluent motion. In Bach’s solo cello and violin works, multiple stops often function as harmonic anchor points: these chords can be seen as vertical snapshots in the network of the different horizontal voices. Considering the importance of the figured bass or thorough bass in Bach’s music, the matter is to extract a plausible bassline by connecting the lower notes of the compound melody and the multiple stops (ex.4).

The intellectual challenge to extract and to connect the significant functional bass notes can be extrapolated to the upper voices. Analysing the solo violin and cello works like this, it is really important to keep in mind that Bach had to be pragmatic when conceiving multi-layered music for a monophonic instrument: some (chord) notes can’t be played, some should be added, others should be displaced.

Reasoning from the perspective of a figured bass, considering the different compositional techniques and respecting Bach’s specific notation, I tried to reduce most of the movements of the cello and violin works to convincing three-part pieces, while still respecting the rules of counterpoint (ex.5). From this viewpoint, Bach’s language here does not differ that much from that of his other multi-voiced works.

Despite the fact that my contrapuntal reductions are not completely objective, I believe my analyses can shed some new light on the polyphonic mindset of J.S. Bach. I hope they can be an interesting and useful resource for any violinist, cellist or musicologist, especially when practising these masterpieces. My analyses are not intended to be dogmatic. On the contrary, they are primarily meant to be thought-provoking. I strongly believe in the importance of mutual cooperation between performers and musicologists, especially in this niche area. We can learn a lot from each other.

If you’re interested in my research, please email me: laurent_matthys@hotmail.com or visit my YouTube channel ’The Lost Art Of Counterpoint’

I can offer analyses, (online) lessons and passionate, interactive masterclasses for violinists, cellists, theoreticians and music lovers.

Read: Why you shouldn’t practise Suites and Partitas with a metronome: Ulrich Heinen

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

Reference

Lester, J. (1999). Bach’s Works for Solo Violin: Style, Structure, Performance. Oxford University Press.

Winold, A. (2007). Bach’s Cello Suites, Volumes 1 and 2: Analyses and Explorations. Indiana University Press.

No comments yet