Psychoanalyst Mavis Himes presents an excerpt from her memoir, which explores her musical journey of learning the cello later in life

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

In 2018, at a time of life when I was contemplating my retirement, and along with it, the inevitable reality of life’s impermanence on this planet, I decided to take up the study of the cello. In fact, I wrote an article about this that was published in The Strad in 2022.

From the beginning, my cello teacher encouraged me to think of my musical studies as a journey, an odyssey into uncharted and unfamiliar physical and mental territories. As part of my daily ritual, I was encouraged to keep both a lesson journal, in which to record important teachings from my lessons, and a practice journal in which to notate my weekly plans, objectives and progress. In addition, I decided to keep a diary of my musical voyage including personal thoughts and ideas, concerts attended and all music-related activities. I wanted to document and archive this new learning, with the hope of discovering new insights.

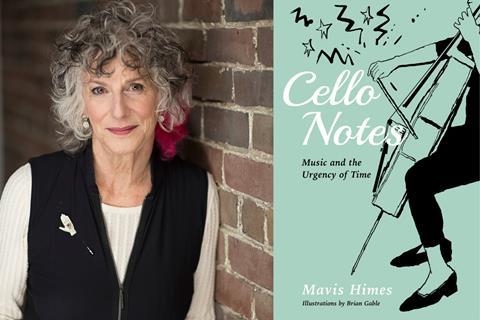

This writing led to the recent publication of my book Cello Notes: Music and the Urgency of Time, a memoir about the importance of dreaming big and pursuing one’s desires at any age. The initial title was to be The Urgency of Time, but in fact, the deepening of the process and unforeseen circumstances, made me realise that a shift from urgency to acceptance of life’s timeline had become a critical aspect of my transformation, both musically and psychologically.

Since the time of writing, my repertoire of music has expanded to include weekly participation in an amateur string orchestra, as well as the occasional playing in a string quartet. The bonus pleasure of making music with others has accelerated exponentially my musical development and excitement, not to mention the surplus benefits to my brain’s grey matter.

Here is an excerpt from Cello Notes: Music and the Urgency of Time:

Into the beginning of my third year, practising was an ongoing application of drill and sweat, frustration and persistence. In taking up the cello, I’d rediscovered the traditional meaning of the word praxis: ’to perform (an activity) or to exercise (a skill) repeatedly or regularly in order to acquire, improve, or maintain proficiency.’

Every day, I removed Daisy, my cello, from her stand, wiped her down with an anti-static cloth, tightened the hairs of my bow loosened the day before, and set up my sheet music. Before touching the instrument, I performed a series of arm, shoulder, and hand exercises to warm up my muscles and joints, anointing my body thoroughly for the movements I was about to demand of it. I tried, usually unsuccessfully, to include a few moments of breath work and self-composure. Then, sitting on my wooden stool, I tuned my cello to Soundcorset, an app on my cellphone that ensured amateurs like me could begin in tune.

What was practising in music? Many articles, old and new, circulated and continued to be disseminated around the topic of practice. Of course, no two were ever in total agreement. Take for example, these two tips on flexible bow holding in practice published in The Strad a century apart, the first by Arthur Broadley in 1905, the second by Simon Fischer in 2005:

’In order that the muscles of the fingers, wrist, and forearm may be properly developed it is absolutely necessary that every portion of the bow should be properly practised. This cannot be accomplished in a few weeks or even a few months — it is a case of growth, and all growth is by nature a somewhat slow process.’

’What is the best way to hold the bow? There is no single answer to this question, since the exact bow hold changes constantly according to what you are playing. The question should be, “What is the best way to hold the bow to play what?” To play very heavily or strongly, you might grip the bow quite solidly and spread the fingers more widely to get more leverage. To play with more delicacy, or to produce a particular dolce or special feathery sound quality, you might hold the bow so that there is barely any feeling of contact at all between it and the fingers; and allow the fingers to remain a normal, natural distance apart rather than spreading them out.’

Was practice just the training of muscle memory? Was it only to ensure through repetition the grafting of muscle memory onto the instrument? Repetition invisibly and mysteriously established neurological connections. I marvelled at the way our brains laid down pathways for such minute body movements in each part of our hands and arms like an invisible pattern of lace filaments etched by a master embroiderer.

Dobrochna also insisted that if we could attune our ears to hear the notes internally, our fingers would gravitate and direct us to the correct placement. The body never ceased to amaze! Practice also established the repetitive rehearsing of the fingers in the perfecting of scales: first for position, for speed, for correct connections of the shoulder-elbow-hand triad, and finally, for weighting on the bow. One long bowing equaled one elasticized note per bow without a change of bow direction; two notes per bow involved the shifting from down to up bow after every two notes, then four notes per bow, then eight, then sixteen at express speed.

The practices of sitting zazen (Zen meditation), daily walking, and regular routines shared by friends and colleagues were other things I thought about. Practice had already become a regular feature of my daily life, a repetitive mantra that ensured ongoing continuity and memory.

Yet more importantly for me, practice became a sacred time and place. Aside from my occasional cynicism and discouragement, I came to view practice time as hallowed and sacrosanct, an activity set apart from the rest of my day, like a daily Sabbath break. Playing within the solitude of my private space, I could experiment and relax. I swooned with Daisy in my arms in a lyrical passage, admiring my proficiency, cringed and stomped the floor when I consistently missed notes, making micro or macro errors in intonation.

Cello Notes: Music and the Urgency of Time is available now at https://www.mavishimes.com/books

Read: Learning the cello as an adult: Mavis Himes

Read: Adult beginner cello: Never too late to learn

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet