Ivry Gitlis’s lessons with George Enescu focused purely on the music. From October 2013

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

This article appeared in the October 2013 issue of The Strad

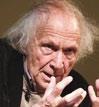

The first time I met Enescu I was a little boy – we’d just arrived in Paris. I heard him play with the pianist Céliny Chailley-Richez, who was the wife of one of my teachers. I was presented to him and he found a picture of himself for me and signed it, ‘Patience et courage’. I often wondered what he meant: I think I know now, more or less.

I spent a whole summer working with him, and it was very intense. He liked me and gave me a lot of his time. He was always at the piano. He would play everything – sonatas or concertos. It was like being carried, as if you were a small boat and this river was carrying you with it. The whole of his body was music: the way he held the violin, how he phrased and sculpted the musical phrase. I absorbed it like blotting paper.

I thought about him as if he were from another planet, an alien; as if he’d descended upon Earth to bring an offering. He was simple and humble, modest in many ways, and he shied away from any kind of ostentation. His message was very clear so you didn’t have to know what that message was in words. It went into the pores of your being and became part of you. I can trace many things in my own music making from there, as though he impregnated me with what he was.

There were no scales. We didn’t study violin playing. The violin was the music, unlike other teachers: for him it was music, music, music. He wouldn’t talk about up and down bows, but he’d speak of mountains, the sun and the sky. He lived something with you. It was not telling you to do this or do that. It was much more effective: you really experienced a life journey with him.

He often changed markings in the score when he wanted more or less expression. If you let yourself be led by the music, it will always bring you where you have to go – he was like that, and I probably got this from him. He was a great composer, one who, like Bartók, came out of the people, out of a folk tradition. He was infused with the music of his land. His works are influenced by Romanian folk musicians – his Third Sonata ‘dans le caractère populaire roumain’, for example. Because he was a creative artist, when he played, it was like he was composing the music.

Read: Great string players of the past: Joshua Bell on Eugène Ysaÿe

Read: Great string players of the past: violinist Fritz Kreisler

I heard him many times after I studied with him, playing the Bach Sonatas and Partitas, the Brahms sonatas. His sound was very open, although it’s difficult for me to remember exactly. He was pretty virtuosic in his earlier days. It’s amazing to think that in the same period there were also Kreisler, Thibaud and Casals. These people spoke in their playing. They told you stories. They explained things, without necessarily telling you what.

Towards the last years of his life his back was completely curved, like a hunchback. I don’t know how he managed to perform. Even hearing him perform at a Wigmore Hall recital in these years, the playing was very beautiful. He still sounded so young. His personality as an artist dominated his capacities, or incapacities.

People like Ensecu were not only public figures who played the role of public figure; they were what they were. Today there are so many things going on that stop us from seeing properly. Everything is so available without our having time to distinguish what is worthwhile and what is not. What Enescu taught me is not to take things as they are, or as they seem to be, but to go into them and look inside yourself. What is your response to the notes you’re seeing? Otherwise it’s just notes on a piece of paper, like little flies – it doesn’t mean a thing. I love the story about the conductor Otto Klemperer: someone came to him and said, ‘Maestro, to me you are like God, but why do you use the music when you conduct, when most people don’t?’ Klemperer said, ‘I use the music because I know how to read it!’ Maybe Enescu taught me a little how to read the music.

INTERVIEW BY ARIANE TODES

Read: Great string players of the past: Violinist Bronislaw Huberman

Read: Great string players of the past: Cellist Pablo Casals

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet