The violinist draws on his experience of transcribing Philip Glass’s music to offer general advice on the transcription process

I remember walking off stage in New Zealand after a recital tour in 2008 with pianist Isabelle O’Connell. It was the first time that I had created a series of arrangements for violin and piano based on beautiful Irish melodies. By arrangements, I mean that I cut out parts from flute, vocal, cello and tin whistle along with somewhat patched-together piano scores. Isabelle was so very gracious in giving these arrangements such musical conviction. Never had I been more stressed in taking the risk to programme these beautiful musical pieces, but also so elated by the audience’s reactions to them. After that particular concert in Te Awamutu, just outside Hamilton, sitting down for dinner with Isabelle and my Dad, I resolved to polish and hone my skills, and create something more structured for the public to enjoy.

The more I think about it, the more I realise that I’ve always been fascinated by violin transcriptions - those of Fritz Kreisler, Leopold Auer, Nathan Milstein and Jascha Heifetz all captured my imagination when I was a child. And I had the pleasure of having the violinistic voice of Milstein and Heifetz in my head as my teacher Erick Friedman was a pupil of both. Spurred by that concert in New Zealand years ago, I started embracing writing my own transcriptions and creating arrangements, performing them on the world’s stages. They range from Bach’s ‘Toccata and Fugue’ BWV 565 to the ‘Goldberg Aria’ for solo violin; arrangements of Dave Brubeck’s ‘Blue Rondo ala Turk’ to Johnny Cash’s ‘Hurt’ for violin and orchestra; and innumerous transcriptions from Astor Piazzolla and Bill Evans to Ennio Morricone for ensembles such as jazz quartet or my signature combination of violin and 2 cellos. There is a thrill in hearing your works and creations come to life no matter the group with whom you perform.

A number of years ago I heard the music composed for the film The Hours by Philip Glass. Watching and absorbing those sounds, I sensed the score really speaking to me. I felt that there could be something beautiful in creating a transcription for violin and orchestra that was a throwback to the transcriptions of Heifetz & Milstein and what they created for the violin repertoire. So, where do you start?

As with anything, start by choosing music that emotionally speaks and resonates with you. From there, create and plan out your musical sketch of the work. I would always choose music in which you feel you have something individual to say, irrespective of whether you are reimagining a simple piano or full orchestral score. Why else create in the first place? In relation to ’The Hours Suite’, I wanted to keep the harmonic structure of the original score constant throughout. The fun part of the arrangement was being inventive with the violin line and making that homage to the Heifetz & Milstein transcriptions of the past. The aim was to add a melodic line that embellishes the score while providing the driving force for the harmonic structure.

Now that you have the score sketched out and your ideas developed, consider how each section can bring something different to the music in terms of quality of sound, character of tone and sound effects. In general, the violin maintains brilliance of sound whereas the viola has more of a nasal sound. The cello contributes that glorious chest voice and the double bass is so grounding and penetrating. There are so many varieties and textures of sound that add depth and meaning from pizzicato to ponticello, col legno to con sordino, legato to spiccato and double-stopping to harmonics.

Read: What to do when you’re ‘Zoom’ed Out’

Read: 5 reasons why I love playing viola transcriptions

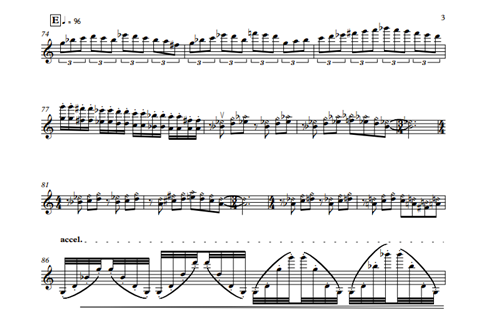

With the full score now sketched out, it is time to start polishing all the written parts. I focused on the solo line, first taking care to add the virtuoso embellishments and additions to the part in a way that felt organic to the score. From harmonics to double stops and arpeggios to octaves, the sounds of old vinyl RCA records came flooding to mind as I applied some old school techniques to a modern master. (See attached example from the violin score.) When it came to the orchestral parts, as a string player I wanted to play through each part so that they made sense to the eye and ear. When you read through each part, monitor accordingly so that no measures contain awkward voice leading, stubborn double stops or areas that are overexposed for tuning. If you are recording your work, the fluidity and facility of the part for the orchestral player has an importance to play in effectiveness of time and cost during the recording session. As a rule of thumb, I like to leave the individuality of the finer points of bowing to the section leaders so that they can circulate those throughout the section. For any arranger, bowing can be a minefield, but bear in mind that time is money when it comes to recording, so be meticulous in making as many markings in the score as possible to facilitate to session.

As the Violin Concerto No. 2 ’American Four Seasons’ was written for violin solo and string orchestra (with synthesizer) I wanted to keep the same orchestral forces for ’The Hours Suite.’ While we all have delusions of grandeur of having and writing for a massive symphonic orchestra, you can get an incredibly pleasant, rich and lush sound with 25 players: 14 violins, 4 violas, 4 cello and 3 double basses. The violins are traditionally sub‑divided into first and second violins with the firsts outnumbering the seconds — and for melodies and lines in the first violin section to shine, I wanted that 8:6 split between firsts/seconds, giving an ensemble line‑up of 8/6/4/4/3. That gives the melodic line the sheen it needs. When you get the balance of orchestral forces nicely weighted, that rich timbre, powerful and emotional expression can create a stirring sonic experience that makes the hair on the back of the neck stand up.

So, how does one approach arranging for strings:

1. Your overall sound will benefit from you writing each part separately. Your arrangement will sound more organic and you will give the music the opportunity to flow and breathe. Rather than writing just a series of block chords where each player changes note at the beginning of the bar, giving independent melodic movement to each part provides the player with the chance to add expression and allows them more emotional investment in the part. With emotional investment, you get more commitment. Once that is done, review each part again to ensure that the line can stand alone.

2. Choose the right key signature. This can be important when it comes to string sonority and resonance. Five flats won’t sound as resonant as a key signature that allows open strings to come into play (unless, of course, you’re working with singers rather than string players). This can reduce recording time significantly due to tuning and the way the part fits in the hand.

3. Remember that the beauty of a small string ensemble can be its percussiveness as well as its lyricism, and don’t be afraid to steer clear of clichéd notions that the melody belongs to the first violins while the bass line remains the preserve of double basses. Entice the violas with a beautiful bass line, or enlist the higher register of the A string on the cello to let it sing. The musicians will thank you!

4. It goes without saying, but stay within the range of the instrument.

5. Try to avoid writing unison passages between both violin sections as it can create a rather thin sound.

6. Don’t get too dictatorial about the bowings in your arrangement. Pen your overview but leave it to the section leader to disseminate bowing through the section.

7. Lastly, if you are unsure, seek help from other musicians and instrumentalists. We love to give our opinion and while it is only one point of view, it can help to steer your ideas towards become more concise and clear.

Now that your arrangement is complete, the last thing to consider is the presentation or part writing. You can outsource this to a copyist or you can consider being your own copyist. Whichever option you choose, your arrangement has to be set on paper in a way that can be easily and accurately sight‑read by the players. It is worth the investment of hiring someone, but I do encourage you to learn this valuable skill – as it is definitely not something you can master overnight. More importantly, doing an improper job will cause confusion and mistakes in the rehearsal or studio while everyone tries to figure out the solution. That can turn out to be very costly.

Gregory Harrington is a concert soloist based in New York City and a speaker on the music industry. Sign up on his website gregoryharrington.com and download his new album Glass Hour on Bandcamp

To continue the conversation feel free to contact him at greg@gregoryharrington.com or follow him on IG @harringtonviolin

No comments yet