A powerfully expressive chamber work by one of the most important British composers of the interwar years failed to make it into print – but why? As Rebecca Clarke’s 1923 Rhapsody for cello and piano is published for the first time, John York, who recorded the piece with cellist Raphael Wallfisch, considers the evidence in The Strad December 2019 issue

Why it took nearly a century for an important, beautiful concert piece for cello and piano from a 20th-century female composer to be published is incomprehensible. We can certainly blame contemporaneous sexist attitudes towards women, but was there also something more personal here?

The Rhapsody for cello and piano by Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) was the last in a series of three works supported by the rich and powerful American patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (who commissioned only a few female composers but many male ones). The British composer’s Viola Sonata had nearly won the big prize at the 1919 chamber music competition in Berkshire, Massachusetts. It was only denied the top award because the judges did not believe a woman could write such excellent music. (The winning composition was Bloch’s fine Suite for viola and piano, and the judges opined that he’d probably written Clarke’s piece as well.) This gross injustice did, however, bring Clarke one piece of good fortune, namely the support and friendship of Coolidge herself. Shaking off the judges’ snub, she went ahead and produced her very effective Piano Trio (1921) and the Rhapsody (1923) for cello and piano.

Watch: Richard O’Neill plays Rebecca Clarke viola sonata

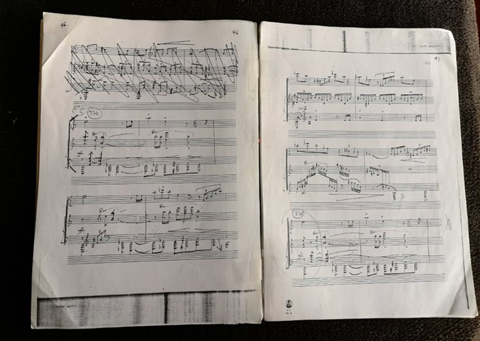

A hand-written page of Clarke’s Rhapsody manuscript Courtesy BBC Music Library. Main image Tully Potter Collection

It is interesting to note that there was a flurry of exceptional cello works produced in England around the end of the First World War. Delius’s Sonata and Concerto, the Bridge Sonata, the Elgar Concerto and the Ireland Sonata – all these popular, successful works appeared between 1916 and 1923. The common link was Stanford, who taught composition at London’s Royal College Music and who worked with or supported all these composers except Delius – and he was Clarke’s teacher, too.

Her Rhapsody should have achieved the same level of success.

The manuscript score was evidently worked at with diligence by its (probable) dedicatees, cellist May Mukle and pianist Myra Hess. It shows all the visible signs of thorough discussion and perhaps arguments between the three parties. Passages are scratched out; notes and accidentals are altered; fingerings are written in, assertively and instructively; shortcuts are suggested and confirmed, presumably to tighten the structure. Here and there, whole passages are inserted or given a second version.

At an advanced stage in these preparations the score seems to have been withdrawn or rejected – but by whom?

To read the full article, Into the Light, in which John York makes the case for Rebecca Clarke’s 1923 Rhapsody for cello and piano, click here to log in or subscribe

The digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Female violinists of 18th-century England: Portrait of a lady holding a violin

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

Currently reading

Currently readingHow a forgotten chamber masterpiece finally saw the light

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

No comments yet