The meeting between violinist Giovanni Battista Viotti and bowmaker François Xavier Tourte was one of the most important collaborations in the history of string instrument making, as violinist Sophie Rosa explains

The relationship between player and instrument maker has been vital throughout musical history. This was particularly evident when Giovanni Battista Viotti arrived in Paris in 1782, having firmly established himself as an eminent violinist, teacher and composer. Musicians of the time were pushing the boundaries of instrumental techniques and searching for a more diverse range of expression in their playing styles. Viotti, being a leading pioneer in his field, was naturally at the forefront of this development. Set against the backdrop of eighteenth century innovations and The French Revolution, bow makers had been experimenting with new materials and designs since the beginning of the classical period. Of the resulting Transitional classical bows, the Cramer design proved to be the most popular. With a longer, concave stick as well as a heavier and taller head, this was the first step towards achieving these new ideals. However, for Viotti the Cramer model still did not go far enough.

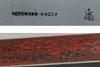

When Viotti heard of the great reputation of François Xavier Tourte and his family, he seized upon the bow maker’s expertise to help design a bow that reflected his artistic aspirations. Their meeting, described by the Belgian musicologist François-Joseph Fétis in 1856, was set to be one of the most important collaborations in the history of string instrument making. There were several profound changes made to the design by Tourte, which followed on from the Cramer model. In addition to the lengthened and concave stick, the head was lightened whilst retaining its strength. Thanks to new techniques in cutting and curving of the stick, the grain ran uniformly along the length of the stick allowing for greater stiffness and strength, the ferule and the spread wedge were invented to spread the hair more widely, and the ideal distance between the bow hair and stick was established. Metal fittings and head plates also made the bow more durable. While sources are limited, there is evidence to suggest that Viotti had particular input with flattening the ribbon of the bow hair. The pre-eminence of pernambuco as the wood of choice also played a huge role in creating more responsiveness, flexibility and beauty of tone.

Read: Behind the Curve: the evolution of the bow

Read: Hollywood Bow Makers: Unsung heroes of the silver screen

Equipped with the revolutionary new bow, Viotti went on to take the musical world by storm. He developed a new style of playing which eclipsed that of his contemporaries. Players who did not change their technique were left behind and considered old-fashioned. Some even chose to retire, such as the distinguished Maddalena Lombardi-Sirmen – a disciple of Tartini and one of the greatest violinists of her generation. Viotti was now able to sustain the sound more evenly throughout the bow, producing a fuller and more legato tone. The greater tension and elasticity allowed for springing strokes such as sautillé and ricochet, as well as more bite for martelé stokes. However, it was with the legato and broader strokes that Viotti had the most impact. The obsessive and almost cultish following by other violinists, including Louis Spohr meant that lighter springing stokes even went out of fashion for a while. Instead, legato on-the-string articulations were highly favoured, especially the broad detaché bow stroke played in the upper half of the bow.

The legato style of playing was closely linked to ideals in the early Romantic movement which favoured a singing and lyrical expression in sound and delivery. This is evident in many of Viotti’s compositions where he would not only showcase the new bow strokes but also his flair for Italianate singing melodies. A bel canto style in instrumental composition was emerging in parallel developments in piano writing by, among others, the pianist Hélène de Montgeroult. Like Viotti, Montgeroult was greatly influential in piano playing and composition with her 114 Études de difficultés progressives, published in 1816. In the preface of the compendium, she advocated the imitation of the singer’s art, much akin to the cantabile style Viotti was championing on the violin. As duo partners, the two enjoyed a close musical rapport and friendship and they would spend time improvising together as well as giving concerts. Their influence on each other was all the greater for the new possibilities of expression afforded by the new instruments of the time.

Read: In search of perfection: finding the right bow

Read: Trade Secrets: Making a Tourte-style eye

By the early nineteenth century, Tourte’s bow was now so inextricably linked to the great violinist that is was described in Michel Woldemar’s 1798 violin method as L’archet de Viotti. Following the tradition of the time, bows would often be named after the great players - the Corelli, Tartini and Cramer bows all being previous models - while the bow makers themselves would remain anonymous. It was only after the 1750s that archetiers began to stamp their bows in order to gain their own identity and reputation. Viotti’s new playing style, intrinsically linked to the Tourte bow, was consolidated by its immediate uptake by the Paris Conservatoire, established in 1795. Viotti is considered to be the founder of the 19th century French violin school and his legacy was continued by violinists such as Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode and Pierre Baillot. Their études are still used by students today and remain a cornerstone of violin pedagogy. The Tourte bow, closely associated with the French violin school, was firmly established as the standard bow design and favoured above all others. The illustrious reputation of French bow making was thereby permanently cemented.

The significance of the partnership between Viotti and Tourte is still relevant to the modern day, where parallels can be drawn between today’s luthiers and players. The mutual sharing of skills and ideas is a connection that will always remain important into the future.

Sophie Rosa’s new disc with pianist Ian Buckle - in which she plays Viotti’s Violin Sonata No.10, demonstrating new bowing techniques and the change in style of playing - is out on Rubicon Classics at the end of February. The disc also includes sonatas by Weber, Mendelssohn and the world premiere recording of Sonata in A minor Op.2, No.3 by Hélène de Montgeroult, a French composer who was working around the turn of the 19th century and the first ever female professor to be appointed at the Paris Conservatoire. For more information on the disc click here.

See below for a trailer for the disc

See below for an excerpt of Sophie Rosa playing Viotti’s Sonata No.10 in E major

No comments yet