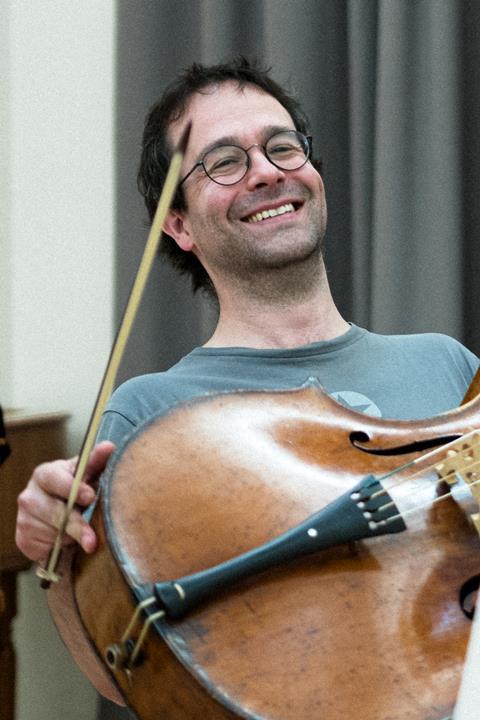

As he prepares for his performance at King’s Place on Sunday 2 April, Christopher Suckling muses on what we know, and what we don’t, about Bach’s Cello Suites

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The Bach Cello Suites have, over the last hundred years or so, acquired a certain cult status, indeed, for many cellists, they have become a defining influence. For such famous music, however, we know relatively little about the suites. This is undoubtedly a good thing; history has left us with many creative spaces in which to play. Here are just a few of the ideas I have been toying with while preparing my latest iteration of the suites.

Preparation is very different from performance. Even though I can audialise the King’s Place acoustic as I listen to myself in my music room, I know that how the sound feels in the hall will move me in unexpected ways during performance; touch is critical to my interpretation. It is here that elements of historical performance practices – both those that are our best approximations of the past and those that have become our current traditions – enter my preparation. The balance of the baroque bow, the resistance of the stick and the string, encourage my arms to dance (even if my legs can’t). At the same time they encourage rhetorical articulation.

Discussion of the manuscript sources for the suites has been extensive and remains current; I won’t rehearse these arguments here, except to note that the manuscripts’ flaws demand that every bowing decision by the cellist has meaning and that, with the baroque bow, these articulations are at the heart of expression.

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #20: Steven Isserlis on consulting musical editions and manuscripts

Read: Bach Solo Violin Partitas: Lord of the dance

Read: Bach Cello Suites: What do we really know about Bach’s Cello Suites?

The music expresses the genius of the dance, but the relationship between dance and music is not straightforward, not least because Bach could dance – as a basic part of his education – and we, for the most, cannot. Even so, the Allemande was no longer danced by Bach’s time (could that be why it is the most exploratory of Bach’s movements?), his Courantes flirt between the French and Italian styles, and his Gigues are frequently more appropriate for fiddling. Tormod Dalen beautifully demonstrates how Bach derives his music from dance, whilst Cooervits and Moelants make clear the different historical instincts of contemporary musicians and dancers.

The dance suite is a French form, as musically influential as the French language was across Germany in the early eighteenth century. Bach’s dancing masters were French and, collated, the ornamentation in the manuscript sources of the cello suites begins to look suspiciously French. Bach’s didactic ornament table was borrowed from d’Anglebert; an analogous table for the viol (including two types of vibrato!) prefaces the suites by Le Sieur de Machy. Charles Medlam conjectures how Bach may have come into contact with these and other French viol suites; reading through these alongside practising Bach asks another question, how ’French’ to play Bach?

Christopher Suckling is continuo cellist with the Feinstein Ensemble and the Gabrieli Consort and Head of Historical Performance at Guildhall School of Music & Drama. He will perform Suites nos. 3, 2 and 4 at Kings Place on Sunday 2 April, 6pm. More information can be found here.

Read: Did Bach dance? Stylised dance in his Solo Violin Partitas

Read: The rhetorical nature of Baroque music: learning to speak with the bow

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet