Charmian Gadd shares the life story of violinist Richard Goldner, who changed the musical landscape of Australia and beyond, culminating in the formation the eponymous quartet

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

In 1939 Richard Goldner, his brother and their two wives arrived in Australia. A refugee from Hitler’s Vienna, he kissed the ground as he descended from the ship in Fremantle - probably not such a good idea as it was a heatwave, but the miraculous nature of the escape had to be acknowledged. Australia was their new home. They would speak only English.

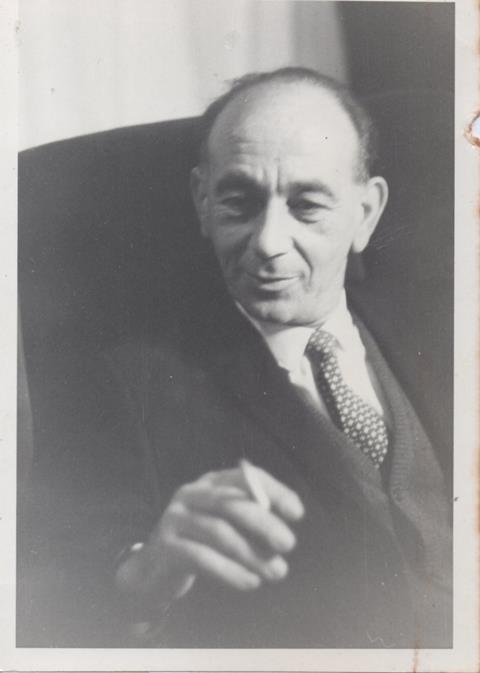

Richard was first and foremost a musician but with his brother Gerard the two boys made things, - lampshades for Russia and jewellery from casein, a precursor to plastics. He invented things, like a special mute for violin and viola that could be initiated by the chin, suitable for the contemporary music he was playing in Hermann Scherchen’s Musica Viva Orchestra. His greatest love was chamber music, and he had the honour of playing in the chamber orchestra of Szymon Pullman; four string quartets coached by Pullman and was known at the time as the finest in Europe. The Viennese public claimed so and with repertoire like Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge and Alban Berg’s brand-new Lyric Suite, I can imagine the claim could be substantiated. There were many fine Jewish musicians in Vienna who were not allowed to play in the State orchestras. Pullman had their enthusiastic services.

The Goldners settled in Sydney and began making costume jewellery. Richard was offered the job of principal viola in Sydney Symphony Orchestra but that was rejected by the musicians’ union at the time. When war was declared he was approached by the Army’s Inventions Directorate, as some of his inventive exploits had been written up in the local newspapers. They needed a zipper for dive bomber suits. Richard lived in Manly at the time and was not allowed to drive as an ‘enemy alien’. So, each day a police car came and transported him to the army office. Much to his surprise he cracked the problem and ended up with a patent on a new mechanical principle, the double helix. 20 years or so later Francis Crick and his fellow scientists revealed this to be the shape and mechanism of our DNA. I sometimes wonder if Richard could have sued God for violating his patent!

He managed to sell this patent for what he considered a princely sum and set about forming a first-class ensemble in Sydney. Meanwhile, sitting in his dentist’s waiting room he had read that Pullman and the entire orchestra that he had set up in the Warsaw ghetto had been captured by the Germans and taken to Treblinka where they perished.

Read: Violins of Hope In Pittsburgh: Timing is everything

Read: String education in regional Western Australia: Sitting on a gold mine

The first concert of Richard Goldner’s Sydney Musica Viva took place in the Sydney Conservatorium of Music on 8 December 1945. It was a time of great contrasting emotions. The Japanese Emperor had just surrendered following the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A few months earlier Hitler had killed himself and his wife after killing millions of other people. The troops were returning from the terrible places they were sent. Joy and relief were in the air.

Richard had spent much time and money preparing for the concert and it was sold out. Unfortunately, a blackout was declared. The power supply was having difficulties. No novice to facing difficulties, Richard approached Sir Charles Moses, head of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) at the time. He was an Army man and provided Richard with generators and lights for the music stands. Car headlights lit up the entrance to the Conservatorium from the original main front entry and the concert took place in a romantic setting with girls holding flashlights showing people to their seats. Thus, Musica Viva was born.

Richard established his ensemble. He brought violinist Robert Pikler and family from Indonesia where they had been incarcerated by the invading Japanese while on a concert tour with their family light-music ensemble. He brought Theodore (Teddy) Salzman and his wife from Israel. Edward Cockman was a great second violinist and young Moureen Jones a supremely gifted and beautiful pianist.

The Musica Viva ensemble was very successful and played all over Australia and New Zealand. Branches of Musica Viva were established in major cities and volunteer committees often comprising fellow refugees pledged their assistance. However, in the long run it proved not financially viable, and some fine financial minds came to the rescue, notably Paul Moravetz and Charles J Berg.

In the process, Musica Viva changed from being basically an ensemble to become fundamentally a concert agency for chamber music. The ensemble disbanded and Musica Viva took up its position as a major force in Australia’s musical life. Under the lawyerly wisdom of Kenneth Tribe, the financial judgement of Charles Berg and the honorary music directorship of Richard until 1966, it fulfilled a valuable and productive role commissioning new works, encouraging new ensembles, importing top international groups, training future leaders in the Arts and branching out into educational fields.

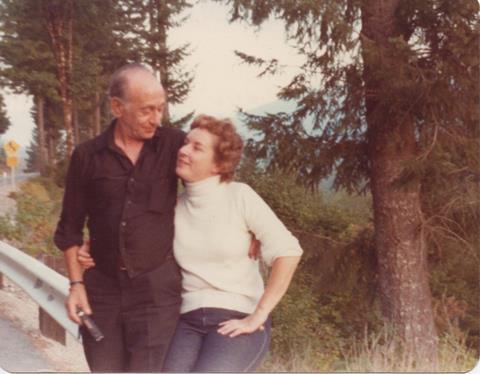

Richard Goldner left Australia for the US in 1966. He received an appointment as professor at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and started a new life, new inventions, new concert series and festivals. Teddy Salzman had settled in Pittsburgh and was a wonderful friend teaching at the rival university. I joined Richard there and we built up a fine string department.

After some publicity a phone call came for Richard, ’Are you the Richard Goldner who played in the Pullman Orchestra in Vienna?’ It turned out to be a member of the Pittsburgh Symphony who was the sole survivor of the Nazi removal of the orchestra in the Warsaw ghetto. He managed to hide under the stage. I was with Richard to observe his reaction to the story. It was gut-wrenching, as he seemed almost as hurt by the musical violation as the human tragedy. The Germans burst into the hall where the group was rehearsing at one of the most sacred moments in music, the slow G flat major central part of the Grosse Fuge.

Richard Goldner died in Sydney in 1991 after returning to Australia without much fanfare in 1987. At his funeral service some friends played; - Dene Olding, Dimity Hall, Irena Morozova and Julian Smiles. They were members of the Australia Ensemble based at the University of New South Wales. They played the Cavatina from the op.130 Beethoven quartet and the slow movement of the Shostakovich Quintet with pianist David Bollard. Soon afterwards they formed a string quartet officially and approached the Goldner family for permission to carry his name, becoming the Goldner Quartet. For 30 years, they have spread joy through their talent and charm. Though we regret that they have reached their final season we are so grateful that they fulfilled Goldner’s dream.

All photos courtesy Charmian Gadd

Read: Goldner Quartet to disband after 30 years

Read: Cornerstones for violinists: the Australian violinist and teacher Alice Waten (1947-2022)

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet