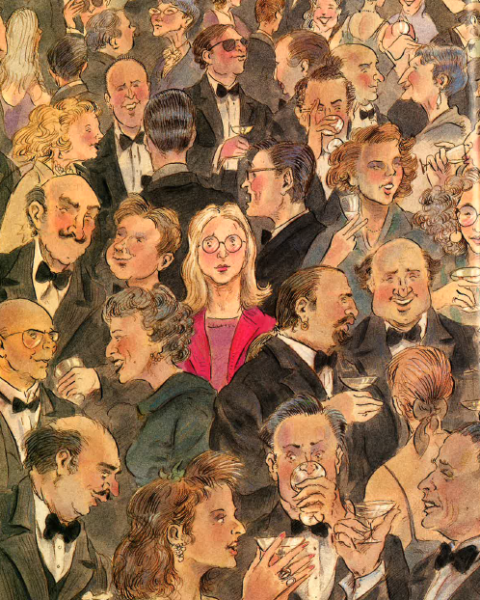

If all you want after your concert is to go home to your hot water bottle, think again: attending that post-concert reception could be essential to your career, says Ellen Highstein

Robert Mann, for 50 years first violinist of the Juilliard String Quartet, tells a story about the group's early days, when they were touring in the Midwest. The reception following one particular concert was due to last late enough to lose them a comfortable travel connection; they would have to drive 40 miles on a cold winter night to a whistle-stop in the middle of nowhere, where they would get a train at 2am to their next town - without a sleeper. They complained, but their management insisted that they had to attend the reception, inconvenient or not.

Finding themselves in the tiny, deserted station house in the middle of the night, they were surprised when a chauffeured limousine drew up and out stepped Arthur Rubinstein. The quartet asked the pianist why he also was there in the middle of the night. 'Because there was a reception after the concert that I played this evening, and I had to stay late for it,' he replied. The Juilliards responded that they didn't understand why he had to do this; it was one thing for them, a young, unknown group, to have to put up with such demands, but why an artist of Rubinstein's stature and renown? 'Because,' he replied, 'l also like to play concerts.'

It is often said in the business that engagements are one thing, but that re-engagements are based on the success of the post-concert reception. Whether this is true is debatable; still, there's enough truth in it to cause an artist to consider carefully how best to handle the extra-musical aspects of concert performance, including all the conversational and communications skills required at the reception, used to talk to the audience during a performance and often needed to get the engagement in the first place.

The many reasons why these skills are important can be summed up as follows: that people want some personal contact with someone they've only experienced at a distance, that they need to make connections individually rather than only collectively and that these connections create understanding and a comfort level that allows them to join you in your musical world. Equally important is the fact that these skills allow you to take advantage of opportunities to talk to your audience, your supporters or your colleagues, and to learn this is as valuable to you as it is important to others, perhaps more so. You should not only get through the reception, but you might be able to enjoy and learn from it.

Musicians can be at a considerable disadvantage in trying to communicate effectively off-stage, since - often - conservatory training does little to prepare you to speak as well as play. We create a host of social insecurities when we encourage musicians to just get back to their practice rooms. However, most artists, when they think about it, are glad that someone has found the time, money and interest to come to a performance; they're pleased that someone will take enough interest in them to spend some time learning about what they do and give them a chance to perform. If the artist really believes this, then saying 'thank you' by making some gracious conversation shouldn't be viewed as painful.

But how can you handle these situations, with precious little preparation for them and with so much potentially riding on your success? Recognising that there isn't any one-size-fits-all formula, there are guidelines, at least, that can help a musician to navigate the social waters of the profession.

At the post-concert reception, it is helpful to put yourself in the presenter's shoes and understand why the event exists. One reason is to thank and honour you, to which (even if you feel that the best thank you would be a quiet evening in your hotel room with CNN and room service) you have to respond graciously. Beyond this, though, it is an opportunity for the presenter to thank those who have supported the event with money, effort, by writing about it or, sometimes, simply by attending - by allowing them to meet you in person. Access to the performer (thereby closing that distance between listener and musician) is the coin of the community, and it is serious business.

You should realise, however, that you should control as many of the circumstances as you reasonably can, to make yourself as comfortable as possible and therefore able to do your best. You don't have to meet anyone before the performance; most concert presenters recognise that artists generally need private, quiet time before concerts, and that they don't usually eat belorehand either. The presenter is as committed as you are to a good concert and is as unwilling to risk it failing as a result of putting too many social obligations on your shoulders before you go on stage. Also, though you will almost certainly need to go to the post-concert reception, you can make requests that will make it easier for you to handle. If you know that you will be hungry (no pre-performance dinner, remember?), you can ask if food will be served, and - if not - ask that they provide you with something to tide you over until you can have a meal. (You should also tell your host about any food requirements you have; if you're a vegetarian and your hosts have kindly provided Swedish meatballs, it isn't going to help you much.)

You can also try to control, or at least influence, the circumstances of how you will meet people, depending on how you're most comfortable interacting with them. Keith Lockhart, conductor of the Utah Symphony and of the Boston Pops and a master at handling such situations, says that he will almost always suggest visiting each table and meeting everyone individually and informally, rather than making a speech to the entire group or standing on a receiving line. (Obviously this only works if there is a seated dinner with tables, but you get the idea.) He is more at ease talking to people this way, and those attending love the greater personal contact it gives them.

What to talk about? Start with listening. The more you can effectively listen to other people, the more likely it is that you can create a real dialogue, even if a brief one, rather than only a standard 'thank you,' followed by a near blank. It is interesting to find out more about the people who have heard, and hopefully liked, your work; you can find out if they're interested in the repertoire you've presented, heard others in concert recently, go to concerts often, have ever studied music themselves, have children, and whether their children take music lessons. What do they think about the new hall, the musical life of the community, the non-musical life of the community? If you know that you're going to be at a fairly lengthy event - a sit-clown dinner, say - sitting with, for example, board members and others from that city, it wouldn't hurt to read the local paper and ask the concert presenter about those you'll be seated with; a bit of knowledge beforehand can put those you're speaking with at ease and its flattering for them to have you take an interest.

Larry Wolfe, associate principal bass in the Boston Symphony, who often has to attend organisational functions, says, 'Look for pockets of honesty and always remain honest with yourself.' It's particularly important not to see these events as false, as opportunities for everyone to impress everyone else. Rather, these are opportunities to draw all interested parties, all of whom have made the musical performance possible, together. Wolfe suggests finding 'areas of mutual interest: children, travel, anything else that may help you learn about them, establishing a common denominator. It can help to have a small repertoire of stories of life on stage, slightly laundered if necessary, which can also make those you're speaking with feel enfranchised into your world. The agenda should be to learn, to enjoy someone's company, not to use people.'

Another conversational technique is always to talk about what you are comfortable talking about. You never want to be confrontational and defensive; life may be long enough for extended arguments with people you don't particularly know, but post-concert receptions are not. Some people view meeting you as an opportunity to either show off their musical knowledge or be particularly critical, or both; its fairly easy to acknowledge that you've heard what they've said ('That's very interesting, I'll have to think about that,') and then go around their comment(s) on to something different that represents solid ground for you ('... but I always enjoy playing in this hall, it's so - pick one - [acoustically warm] [acoustically clear] [close and intimate] [expansive and enormous, and therefore so exciting] [close to the airport...]. You get the picture.

You should have in mind several ideas about what you're playing that will serve you well either during the concert, if you're called upon to speak to the audience, or at the reception. Try to have three things to say about any programme: none of the three can be a date ('Bach was born in 1685' isn't interesting in this context) and at least one of them has to be personal. This can be an anecdote, your own changing perspective on a particular work, something that drew you to play it, or something simply about why you love it.

It's vital to note that nothing you can say, before or after the concert, can make up for a bad performance. But assuming high quality on the stage, generosity off-stage can be incredibly important. And the engaged, supportive, friendly person you spoke with is very likely to lobby for your return engagement and maybe forgive any small errors on stage.

Shaking hands at the reception does qualify as networking - you're not just proxy networking on behalf of the concert presenter or sponsor, doing them a favour, you're also making friends for yourself who will come to, or sponsor, your next performance. But what about 'working the room,' at an event where you could meet individuals who could help you in your career path? This is, in some ways, much tougher than the event at which you're the natural centre of attention. lt isn't easy to avoid looking obsequious, overly eager or just plain annoying (or at least feeling as if you look that way) if you're madly trying to get the positive attention and help of someone you don't really know.

There are a few guidelines here as well which can help - not to get you the management offer, the concert engagement or the audition you really want, but at least to make your interaction with those you meet somewhat more graceful and leave them with a positive impression. First, you can use the formula above, which is to listen, ask questions and do your homework enough beforehand to have some knowledge about those you seek out. Everyone likes to feel valuable, and to feel that you remember, if possible, their name, their accomplishments, their place in the music community. The key is reciprocity: if they feel that you know and value their work, they're more likely to remember and value yours. A manager to whom you've been introduced, for example, will probably be pleased to hear about your appreciation for recent performances by artists on their roster, or your interest in someone new they've taken on. Note that you're not saying that you're available, and how wonderful you are: they're going to have to discover this for themselves, and you're simply trying to create a friendly atmosphere in which they may ask you, reciprocally, about yourself .

A second, equally important point: greet everyone that you should and can, including those that you don't see as being immediately valuable to your career plans. First, its only polite. Second, the musical world is an amazingly fluid one, and those that aren't in a position to help you now may well be so next week.

It isn't possible to maximise every opportunity that presents itself, nor to say all the right things at all the receptions. It isn't possible, or necessary, to be 'charming' all the time; charm is a talent like anything else, and we all have it - or don't - to varying degrees, though we can cultivate it. If is more important to be polite, to be willing to put yourself in someone else's shoes and understand their needs and concerns, and to be, believe it or not, yourself. Your goals should be relatively humble: to respond with generosity to those who have shown some faith in you; to approach with some humility, but certainly with a sense of humour, those who might be able to help you to stay happily employed; to do all this with honesty and remaining true to yourself.

This article was first published in The Strad's October 2000 issue.

No comments yet