The key to successful memorisation of musical works lies in identifying certain approaches that work best for you, writes violinist Alexandra Gorski

Memorisation has long been a concert standard on the classical music stage; solo performances, auditions, and examinations are requiring artists to not only display a deep musical and technical understanding of their work, instrument and interpretation, but to also do it all by memory.

Its often suggested that a performance done by memory indicates a deeper knowledge and understanding of the score, which in turn allows for a freer, more expressive and more personal performance. Of course, an informed, expressive and personal performance is what any musician would call a success- but to rely on our memory for that success can be risky, especially in the high-pressure situations where memorisation is regularly called for.

Although playing by memory can be an additional challenge to an already difficult job, there are ways for players to improve their approach to memorisation. By recognising the different types of memory used when performing, and nurturing the type best suited to the individual, musicians can actively develop strategies towards memorisation, and increase their confidence when performing without the music.

Read: How can I avoid memory slips?

Read: Technique: Memory and mental practice

After dedicated study and analysis of the topic, we now recognise that there are four general types of memory that musicians use when performing - aural, visual, tactile, and intellectual.

- Aural memory is the aspect of our memory that remembers and recognises the sound of the music, allowing us to hear what comes next in our head.

- Visual memory allows a musicians to recall the printed music, markings and important directions - almost like a mental photograph of the page.

- Tactile memory, or muscle memory, is the physical memory of movement, cemented through repetition.

- Intellectual memory is the knowledge and understanding of the structure of the music.

A solid foundation in all four memories is a necessity for successful memorisation, but it is worthwhile to identify which memory a player relies more on, and further develop that memory type. Tactile memory is perhaps the easiest and most natural to develop - once a series of movements are repeated often enough, our muscles become so used to the motions that they can become automatic and instinctual, even if the mind is distracted. Tactile memory allows memorisation to be connected to the body- the feeling of movement a musician makes- rather than dependent on the mind alone.

While repetition is the foundation of muscle memory, playing with ’distractions’ is an excellent way to test your body’s natural recollection of the music. Try practicing with your eyes closed, sitting in unnatural positions, with the TV on, or even walking - anything that could be uncomfortable or unnatural to a performance. Repetitive practice in these altered conditions not only improves your muscle memory, but also offers familiarity to the possible distractions and discomforts that come with performing.

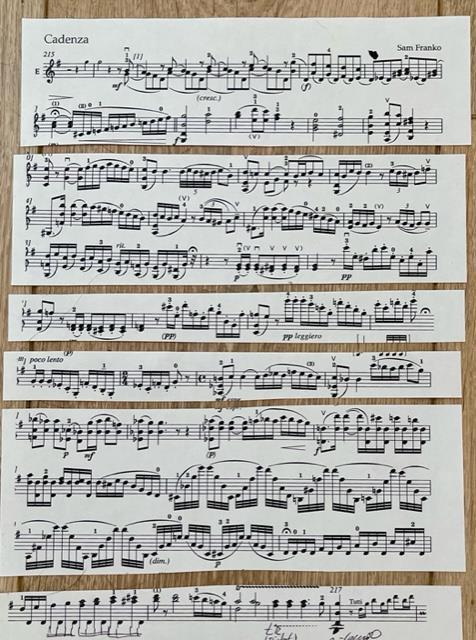

The visual memorisation of music is also dependent on repetition; the repeated exposure of a certain image, in this case our score, so that eventually that image can be recalled. The visual memory of how a page looks - the notes themselves, written markings, even specific dynamics and articulations - allows a performer to reference a mental photograph of their music. Aside from the constant study and re-reading of the score, musicians can actually train and test their visual memory by making what I call the ‘Piece Puzzle.’ Starting with scissors and a photocopy of your piece, cut straight across the page, horizontally and in-between staff lines, creating small sections of varying sizes. The goal is to create individual sections of each page, separate them, and then put the piece back together in the correct order- pictured below.

Unlike a typical puzzle that relies on shapes, ’Piece Puzzle’ requires the musician to read through each section, using the knowledge and memory of their piece to successfully restore each page, while simultaneously training our visual memory and enforcing that mental photograph.

Aural memory relies entirely on sound; remembering how and where a phrase goes, and knowing what comes next in the music. Aural memory, like tactile and visual, is linked to repetitive practice; hearing something often enough that it becomes engrained in the mind. Aside from listening to recordings of the piece or hearing yourself play, singing your part is an excellent way to enforce the aural memory, and can be practiced without the instrument. Singing creatively adds to that repetition of sound, while training the ear to anticipate and remember the music.

Read: Singing during practice can help improve sound and characterisation

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #16: Ayanna Witter-Johnson on playing and singing

Intellectual memory is developed alongside the analysis of the entire composition; understanding the musical structure of a piece, and actively committing that structure to memory. Away from the instrument, a performer’s ability to verbalise that structure further secures their memory; describing in words what happens in your piece from beginning to end; noting that one time the theme goes a certain way, and a different way the second time, which musical clues are offered when in the accompaniment, and so forth. If a musician is able to memorise and explain the structure and patterns of a piece, they essentially create a mental roadmap that can be referenced for the entire performance.

If a musician is able to memorise and explain the structure and patterns of a piece, they essentially create a mental roadmap that can be referenced for the entire performance

Playing by memory is a universal challenge for all musicians - after all, no fear is more commonly shared by artists than the fear of forgetting on stage! By separating, studying and strengthening the individual categories that make up memory, the memorisation process becomes not only more manageable, but more importantly, musicians can achieve security and confidence when playing without the music.

No comments yet