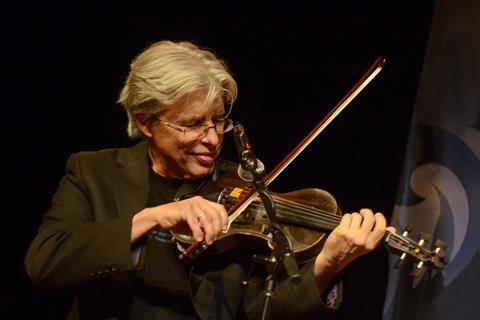

Darol Anger finds a solution for string ensembles performing contemporary music without drums or percussion

To play pop, jazz or any kind of contemporary music within the context of a drumless string ensemble, one must consider the role of drums and percussion as a driving force, supplying the dynamic groove feeling through which the melodies and harmonies entwine. The arsenal of musical techniques and effects used by guitarists and mandolinists has continued to expand in the last three decades, and those instruments are now capable of all the musical roles in an ensemble. How can we in turn, as bowed-instrument players, expand the resources and enrich the character of a small string ensemble?

Since about 1976, I have been developing a technique dubbed the ‘chop’,which was taught to me by the great American fiddler Richard Greene, who invented it while working with Bluegrass music’s originator Bill Monroe in the mid-60s. The sound was Richard’s inventive response to Monroe’s initial advice to play only rhythm behind the other instruments, rather than counter-melodies. When I met Richard years later, he had refined the technique to create a startlingly effective sound, which he taught me. I used it in the David Grisman Quintet and other drumless ensembles for years, before developing it further as an essential musical component of the Turtle Island Quartet’s (TISQ) approach to playing jazz and contemporary music. With TISQ co-founders David Balakrishnan and Mark Summer, I explored the limits of this extremely useful technique. The results have spread far and wide into contemporary fiddle music, and the technique is now being used all over the world in traditional and modern string ensembles.

START WITH THE BACK-BEAT

In nearly all contemporary popular music, rhythmic emphasis is placed on the backbeat, which in a bar of 4/4 corresponds to the second and fourth beats. This gives the rhythm a forward motion and propulsive lift. Particularly in Bluegrass music, the fiddle player will often, when not playing melodies, emphasise the back-beat by making a ‘chop’ sound on the second and fourth beats of a bar of four. That is what we started with in TISQ. The bow is brought down on the string next to the frog, and bounced off, making a ‘chop’ sound rather than a clear note.

We needed to go further, however. Since the TISQ depended on just the four bowed instruments for all rhythmic and harmonic elements besides the melody, we expanded the ‘chop’ into a combination rhythm and harmony strategy, similar to a rhythm guitar sound. We were able to combine the ‘chop’ sound with integrated up and down bow strokes using double-stops and individual notes to convey the effect of a guitar and percussion, or even bass and rhythm guitar. The point in all this sound is to supply a rhythmically and harmonically effective substratum for the melodic lines. But before you explore any groove patterns, it’s important to get the ‘chop’ technique right.

BASIC TECHNIQUE FOR THE ‘CHOP’

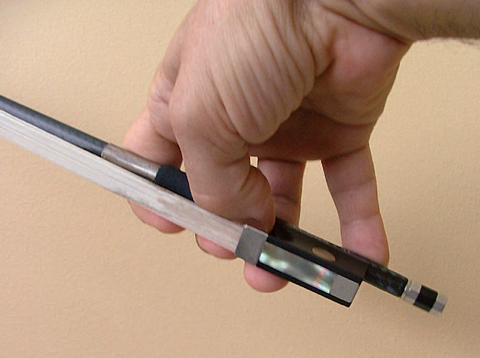

[1] Grip the bow normally, then ‘roll’ the thumb out so that it bends the opposite way (see below). This frees up the wrist, as we must attack within one or two inches of the frog for this technique. The stick will be rolled out slightly to the outer knuckles so that the bow hair is on the ‘far’ side of the stick.

[2a] The bow is brought straight down on the string using mostly wrist motion,making a no-note ‘chop’ sound. The elbow is slightly down, and the arm relaxed. The bow rests on the string. Don't pick up!

[2b] The bow is ‘popped’ off the string with a slight up-bow motion

APPLYING AND EXPANDING THE ‘CHOP’

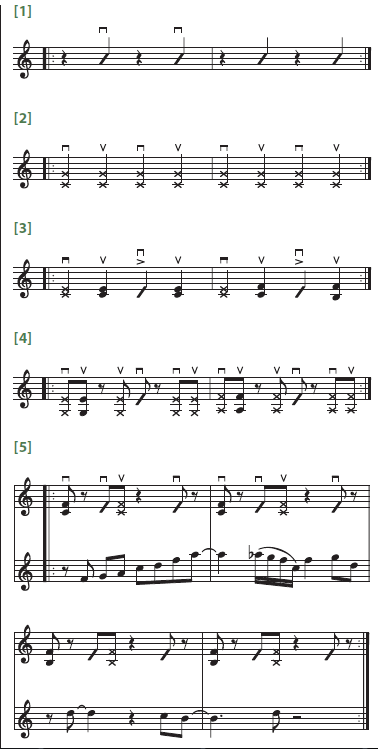

Begin by playing the back-beat figure (example 1), using the ‘chop’ technique explained in [2a] and [2b] above. The slashes indicate a fairly hard attack, with no note sounded.

The next stage is to produce sounds on both the up-stroke and the down-stroke (example 2), with the bow resting on the string between. Here, the x-note indicates a softer attack, still with no actual note, but just the ‘chop’ sound.

I have evolved a small array of bow strokes that are combined into patterns to form various grooves. Example 3 shows the notation for the main bow strokes. In this example, try a soft down-stroke on the first beat alternating with a hard down-stroke on the third beat, which effectively becomes the backbeat in the context of this pattern.

Example 4 shows a simple but effective groove pattern alternating between a C chord and an F chord. To maintain the groove, the up–down pattern is continued through rests, using small, silent bow retakes.

Example 5 shows a complex pattern, toggling between D minor7 and G7 chords, with a jazzy melody under it. This should be played with a swing feel.

This article was first published in The Strad's October 2006 issue.

Technique: Jazz soloing on the double bass

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently reading

Currently readingIntroducing the 'chop': a rhythmic accompaniment for jazz and pop music

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

No comments yet