Canadian soloist and former principal bassist of the London Symphony Orchestra, Joel Quarrington demonstrates how he plays Bottesini’s Elegy in D major. From November 2015

This is my favourite solo piece for double bass. I first played it when I was 14 years old; every year that has passed since has brought me closer to an understanding of its essence. It is a masterpiece of instrumental bel canto, and its place is alongside the great arias of Bellini and Donizetti: its notes are tender, nostalgic outpourings tinged with melancholy, with continuously expressive lines. Bel canto demands poetry in breath, colour and the elegant shaping of every phrase. The whole piece should be in a slow pulse in four, so that when we take our time at the ends of bars as the music divides into quavers (𝅘𝅥𝅮), it creates a beautiful floating quality that captures this feeling of bittersweet reminiscence perfectly, as though we are lingering over a fond memory. The tempo and feel are very similar to those of the second movement of Bottesini’s Second Concerto.

Rubato should always be done in a way that is relative to the central pulse of the music and subdivisions within that. This ebb and flow should occur very naturally, much like breathing. is makes it difficult to give a metronome marking for this piece, but it should be in the vicinity of ♩= 40. The pianist or orchestra – whichever we are working with – should never push the speed of the quavers too much faster than the basic dotted crotchet (♩.) pulse. If they push, I think it gives the piece a bit of a breathless roller coaster feel and takes away the sense of overall calm.

Its notes are tender, nostalgic outpourings tinged with melancholy, with continuously expressive lines

Although the Elegy is in D major, Bottesini used a higher scordatura of a whole tone or a minor 3rd for added brilliance, clarity and projection, so his works appear to the performer to be written in a lower key than they sound. The bassist plays from a part written out in C major, with the strings tuned up a whole tone.

As I write, I am working with three sources: the first two are the Italo Caimmi edition from Ricordi and the version Bottesini included in his Grande méthode complète de contrebasse. Both are available from the IMSLP website, and the latter includes the piano part in C major. I also have the manuscript facsimile from the Parma Conservatoire library archives of the version with string orchestra.

There are differences in all these editions. In particular, the Ricordi contains dynamics, slurs, accents and dotted notes that the others do not. Other editions exist that put some of the higher phrases down an octave or even set the whole piece in a lower key. ese are intended to give intermediate players the opportunity to learn the piece.

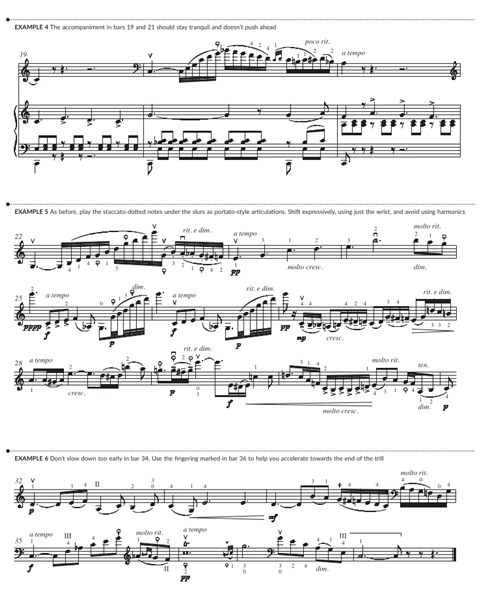

The examples in this article are from my own performance edition, where I have marked the various tempo fluctuations I enjoy, as well as my own dynamics. My slurs are mostly what Bottesini wrote, although I have added some of my own. Please refer to IMSLP for accuracy in authenticity (page 117).

I encourage the pianist or orchestra to take time at the end of bar 1, so that the falling interval of a 7th (D–E) can really be heard in the top voice (example 1). This interval becomes even more apparent when played by a string orchestra, because it fits into the cantabile line of the first violins so well. It should just melt softly into bar 2, like a sigh.

For the bass entry at bar 3 (example 2), I use an up bow. I begin on the first finger because it allows me to vary my vibrato more than the others, and I want to make this note develop in intensity and bloom in colour from the beginning of the bar until the first quaver of the fourth beat. With the accompaniment, that beautiful chord – a sub-dominant with added 4th and 9th – cries out for a tenuto, just so that the music can bathe momentarily in the warmth of that harmony. For the move to that final G of the bar, it is important to preserve the legato; instead of using the left arm to shift, just pull the hand back.

Be careful never to shift quickly or to allow any sort of bump in the sound. Every shift should be inaudible unless we want it to be heard. When we do want it to be heard, there are many di erent ways we can express ourselves, just as with the human voice. e 7th from the E to the D natural in bar 5 is a great example of this.

Never rush that shift! Make sure your fingers and wrist are really flexible, and use them to complete every shift, with very little arm action involved and of course no tension whatsoever. ‘Slow and effortless’ should be the motto. This exibility also makes it possible to pivot from the thumb so that we can encompass three notes in one hand position (see François Rabbath’s Technique article on left-hand pivots in the October 2015 issue of The Strad), leading to an even more owing legato and musical line.

I have included fingerings that make use of this idea. The small shifts in bar 5 should be expressive and smooth. Again, avoid using the whole arm: for these small intervals, the ngers or hand can easily be used instead, while preserving the legato. Prepare backward shifts by moving the thumb away from the hand ahead of the shift and slowly pulling the ngers back towards it. In bar 6, be very careful to make the chromatic scale perfectly even and unaccented. To help, try turning your left wrist slightly each time you do a first- finger shift, rotating it in the direction of the shift.

When dotted notes in Bottesini’s music are under a slur, as they are in the scale of bar 9 (example 3), I would argue that they should be played portato, with an undulating bow, to enunciate the notes in a sustained yet clear and not truly legato manner. Play the first six notes with left-hand pivots; try to keep the left arm fairly still for the last six notes, using just the wrist to move between them, with no shifting sounds. I like to take a lot of time at the end of this bar because it’s very high and dramatic.

Be careful never to shift quickly or to allow any sort of bump in the sound

It would be reasonable to assume that Bottesini intended harmonics to be used on the final two notes of this bar, although he never notated them on his manuscripts. For improved expression, however, I choose to play them closed. I think the very last note of the bar is played best by using just a finger shift: slowly and delicately pull the finger back towards the anchored thumb, keeping the arm very still and relaxed.

Make sure that the demisemiquavers (𝅘𝅥𝅰) at the ends of bars 10, 12 and 14 are clear and not too short. It is important not to play these with mathematical precision: play them more slowly and heavily, to make them song-like and less military in feel. Bars 11 and 13 are very closely related: both have a run with an accent afterwards. Bottesini used accents frequently, and I believe they should always have a heaviness and sometimes even a delayed ‘wah’-like stress.

This is lyrical music, so they should be clear and never have a harsh attack. Another similarity in these bars is that both should have a feeling of release through the fourth beats. I like to stress the falling E–A interval over the bar-line in bar 11, taking very little time but making a sounding portamento; in bar 12 I like to take a lot of time and do a diminuendo to set myself up for the long phrase that finally finishes in bar 19. Some editions of this piece mark accents on every quaver of bar 16. If you own one of these, remember that the accents should only ever be warm articulations and no more. I like the accompaniment to stay calm and tranquil in bars 19 and 21 (example 4); it is important that it does not push ahead.

The last six notes of bar 22 are marked with a slurred staccato (example 5). (There are also slurred staccato passages in bars 9 and 18 of the Ricordi editions.) I interpret these notes as being clearly articulated rather than short, because I do not think that legato, singing music is any place for short notes. Play this bar with a ritardando and diminuendo to set up a lovely swell through the phrase of the next bar and a half.

For the shift from the E to the B at the beginning of bar 24, it is OK to begin the B as a harmonic and then quickly change it to a closed note with molto vibrato. I think it’s great to juxtapose extreme dynamics, so I do something unusual at the end of this bar: I do a molto ritardando and molto diminuendo into the very high note in bar 25. Play accents on the second beats of bars 24 and 25 with a really heart-warming sound, as though they were part of an anthem.

I can’t say often enough how much I recommend shifting using just the left wrist

I come to a full stop after the first note of bar 27, as though after that I’ll be playing something new – a more impassioned declaration of love, perhaps, using the bow as though the music were speech. Every shift throughout the next line should be expressive; don’t go into harmonics if possible. I can’t say often enough how much I recommend shifting using just the wrist.

I like the piano dynamic that is written in bar 29 of the Ricordi edition. I am in favour of Bottesini’s original forte if the note can be played closed, but most double basses don’t have fingerboards long enough to do this. Playing a soft harmonic is a better option, and playing the passage in piano is a very good idea.

Bar 30 features the biggest rubato in the piece. Take plenty of time for the diminuendo and ritardando at the end of the bar; bear in mind that Bottesini wrote colla parte (‘with the soloist’) over both the third and fourth beats of the accompaniment.

A common mistake in bar 34 (example 6) is to slow down too soon, usually as a result of accenting the shift of the second beat. The ritardando should not happen until the fourth beat. In order to make the trill in bar 36 really pianissimo and elegant, I use my thumb and second finger. This allows me to use a very wide range of trilling speeds; I can even accelerate the trill towards the end of the note. If you are careful to change the bow on the lower note of the trill, you can do as many inaudible bow changes at the point as you like, only travelling to the frog for bar 37. Let your trill stop just before playing the grace notes at the end of the bar. The last few notes of the piece (bar 37) are quiet and should stay soft and calm. Bottesini wrote all six notes in one slur, but I find that quite difficult so I break them up.

Don’t pause for too long between the high G and the quavers in bar 37, and don’t reset the bow in any way. Your playing should have had a hypnotic effect on the audience by now, so don’t wreck the mood by moving unnecessarily.

The length of the note in the final bar corresponds with three short pizzicato chords in the string orchestra accompaniment, so when playing the piece with orchestra it is important to do this exactly as written, allowing the silence that follows to be part of the piece. If, however, you are playing with piano, I think it’s fine to add a fermata and allow the note to fade out naturally over several seconds.

![Bottesini_Artwork[DIGITAL]](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/6/8/9/36689_bottesini_artworkdigital_876468_crop.jpg)

No comments yet