On the 121st anniversary of the birth of the great Russian–American violinist Nathan Milstein on 13 January 1904, Robert Levin shares his personal recollections of hearing, meeting and eventually studying with the virtuoso

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

With the passing of Nathan Milstein on 21 December 1992, the era of great Russian violin playing came to an abrupt end. He was one of the 20th century’s greatest exponents of the violin, and although there are many fine violinists appearing before the public today, few, if any, begin to approach the purity, simplicity and elegance of Milstein’s patrician art. He was placed on this earth to play the violin – he was the consummate fiddle player.

I first heard Nathan Milstein in recital at Chicago’s Orchestra Hall in 1959 when I was a young boy of eight. His performances of Pergolesi, Beethoven, Bach, Brahms, Chopin, Sarasate and his own Paganiniana that Sunday afternoon have remained embedded in my heart and soul and will so forever. From that time until I left Chicago to study in New York City at the Juilliard School, I had the incredible good fortune to hear Milstein in recital and with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra every concert season. He was truly a beloved musical figure in Chicago, and the much feared and highly respected Claudia Cassidy, the Chicago Tribune critic whose venomous pen destroyed many an artist’s career, absolutely adored him. I remember going backstage as a youngster after each performance, looking at this idol of mine, shaking hands with him, saying something truly profound like, ‘congratulations, you played so beautifully,’ and wondering if I would ever achieve anything similar to his accomplishments on the violin. I never came close.

Milstein possessed a smooth and rich tone, not unlike biting into a delicious chocolate or touching a sensual piece of velvet

Milstein’s chief rival throughout most of his career in the United States was Jascha Heifetz. They were close in age and were both supreme masters of the great Russian school of violin playing as a result of their studies with Leopold Auer as well as other distinguished Russian pedagogues. Heifetz may have exhibited more imagination in his playing and his performances often had more of an individual stamp to them, but Milstein, every bit as great a violinist, was the purer of the two. Whereas Heifetz’s sound had an incredible edge and excitement to it, Milstein possessed a smooth and rich tone, not unlike biting into a delicious chocolate or touching a sensual piece of velvet. Although his sound was not huge as compared with many of today’s violin virtuosos, it nevertheless soared above and penetrated through all symphony orchestras. Milstein’s tone production, which was refined, focused and pure, was proof that it is not necessary to possess a thick, colourless sound in order to project and fill a 2,000-seat concert hall.

There was absolutely nothing Milstein could not do on the violin and he continued to play brilliantly well past the age of 80, a feat unprecedented in the history of violin playing. His own strong and highly individual personality was never allowed to interfere with the structure of the musical line. Architecture was everything to him, particularly in Bach but just as important in miniatures and encore pieces. This is something that is entirely missing in these modern times. One of my renowned Juilliard teachers, Dorothy DeLay, once told me in a lesson that Milstein’s Bach Sonatas and Partitas were ‘too old fashioned and outdated’. When I asked Ms DeLay whether or not Milstein’s Bach was a work of art, her response was ‘yes, of course’. I then asked how a true work of art can ever be outdated or old fashioned. To that there was no response and things were never quite the same between us.

For those of us fortunate enough to have heard Milstein’s Bach in recital and to own both commercially recorded sets of his Sonatas and Partitas, particularly the earlier Capitol set, we know that this Bach playing is unequalled in its huge architecture, simplicity and simmering passion. Passion was not a word often used in describing Milstein’s playing, but that was only because his passion was controlled and never displayed in a vulgar and tasteless manner. His playing was sometimes misinterpreted as being aloof by unsophisticated listeners who were accustomed to the often overly sentimental playing exhibited by other great violinists of the day. Since Milstein’s death, several live recordings of Bach Sonatas and Partitas have been released on CD and they are all superb performances, played with a bit more abandon and excitement than his commercial recordings.

On a Friday afternoon in 1967 I heard Milstein perform Prokofiev’s Concerto no.1 in D major with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Jean Martinon on the podium. At this point in his life he was suffering from bursitis and was not always playing up to his usual high standard. After the performance, I went backstage and found Milstein alone and obviously disturbed. He was upset because he had received negative criticism in the morning paper regarding his tone of his performance the night before. He asked me what I thought and if I agreed with the critic that his sound was scratchy and that it whistled too much. Here I was, 16 years old, and he was asking me what I thought of his playing. Of course, without any hesitation at all, I told him his performance was fantastic, but I knew from the look in his eyes that he did not believe me.

That same concert season, Milstein returned to Chicago for an Orchestra Hall recital with pianist Leon Pommers. Having studied the violin since the age of five and after winning first prize in several Chicago music competitions, I decided it was time for me to perform for my idol. I had been studying with the pre-eminent Ivan Galamian at the Meadowmount School of Music in upstate New York for several summers and I was convinced that all I wanted out of life was to become the next Nathan Milstein. I remember, as if it were yesterday, finding the nerve to place the call to Milstein’s hotel (he always stayed at the Ambassador East in Chicago) from a pay telephone located in Highland Park High School, where I was a junior. Of course, I should have been in class, but, after all, what was more important, algebra or Milstein? Milstein answered the telephone and I reminded him that I was the young boy who always came backstage at Orchestra Hall for an autograph. I then asked him if he had time to listen to me play the violin. To my astonishment, he invited me to come downtown to his hotel the following afternoon.

I arrived at the Ambassador East Hotel in the late afternoon, the same hotel Alfred Hitchcock used in North by Northwest, called upstairs and proceeded to Milstein’s room. I was rather startled by the unshaven and slightly unkempt man wearing glasses who opened the door and invited me in. I asked for Mr Milstein, assuming that the person who greeted me was a relative, friend or hotel employee, and he replied, ‘I am Milstein’. Up until that time, I had only seen him in the most elegant of concert attire on stage or back after a performance, and never before with glasses. One can imagine my complete surprise and total embarrassment at my faux pas. He was wearing a plaid shirt without tie, an open bottle of scotch was on the night table and he had been watching a western on television. I am not sure what the fascination with westerns was all about, but both he and his dear friend Vladimir Horowitz loved watching them. The aristocratic image of my hero was momentarily shattered. He then asked me what I wanted to play and I chose the first two movements of the Mendelssohn E minor Concerto. I had not prepared the last movement and, of course, that was what he decided he wanted to hear. I was so terribly nervous that I could hardly hold the bow steady and, needless to say, my playing was not so good. After about 15 minutes, Milstein decided to play a little something for me, to show me how the violin should be played and perhaps because he did not want his neighbours in the hotel to think what they had heard was from him. He played the entire Introduction and Tarantella by Sarasate sitting on the edge of his bed holding the violin on his chest, slightly intoxicated. It was absolutely miraculous. I had never witnessed such ease of playing and fluidity of technique at such close proximity. His left hand could only be described as fluid drive and the legato playing in the Introduction and spicatto in the Tarantella were breathtaking and hair raising. I stood beside him, stunned and speechless, realising I would never achieve my goals and aspirations.

He played the entire Introduction and Tarantella by Sarasate sitting on the edge of his bed holding the violin on his chest, slightly intoxicated. It was absolutely miraculous

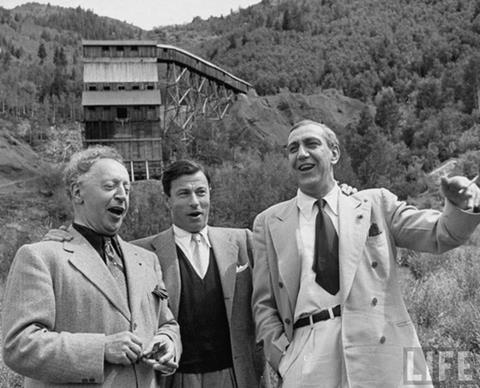

During my years at Juilliard, I went to every Milstein concert in and around New York City, and often traveled to Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington DC, with friends to hear him. We were hungry to hear great violin playing and Milstein was the last survivor of the century’s great violinists which included Francescatti, Heifetz, Kogan, Kreisler, Oistrakh, Szigeti and Shumsky (Milstein considered Oscar Shumsky to be the greatest of all American-born violinists). I spent two summers studying with Milstein in Zurich along with my friend, Bruce Dukov, whom Milstein was very fond of and who served as concertmaster of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra for many years. Mr Dukov composed a set of variations on ‘Happy Birthday’ for Milstein’s 80th birthday celebration at the Bohemian Club in New York City, and it was performed by such noted violinists as Itzhak Perlman, Glenn Dicterow, Erick Friedman, Daniel Heifetz and the composer. The work has since been published. Dukov, Milstein and I spent many an evening walking the streets of Zurich and dining at some of the city’s most exclusive and elegant restaurants. After dinner, we would go back to his hotel and sit in the lobby and listen to Milstein’s fantastic stories and anecdotes about other great musicians, many of which were less than kind, but always very humorous. Many conductors were referred to as ‘shoemakers’.

In 1973, the late Peter Mennin, who at the time was president of the Juilliard School, invited Milstein to give a series of masterclasses at the school. By that time, I had pretty much decided not to pursue a career as a concert violinist for purely practical reasons, and therefore did not actively participate. Some of my colleagues and friends, including Bruce Dukov, Ida Kavafian and Philip Setzer performed, but sadly, many wonderfully talented students did not participate and did not even attend the classes as observers. Apparently, some faculty members, including Ms DeLay and Joseph Fuchs, discouraged their pupils from attending, perhaps because of their own insecurity, pettiness and jealousy. Unfortunately, those pupils who did not take part in the classes were cheated out of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Milstein was a far better teacher than even he himself realised and just to watch him play was magical, enormously enlightening and life changing. Those of us who did attend the classes were extremely embarrassed by the lack of turnout, but Milstein was not too terribly concerned or bothered. I recall him saying during the very first session in Paul Recital Hall, ‘Well, if nobody wants to play for me I will go home and have tea.’ And that is precisely what he did.

It was the child in Milstein that kept him eternally young, in his playing and all throughout his life. He was constantly toying with new fingerings and bowings, experimenting with new ideas

One of the last Milstein recitals I heard was in Carnegie Hall. It was wonderful, and Milstein, in his 80s, was in terrific form. I shall never forget the beauty and charm of the last movement of the Franck Sonata, a work I had never heard him perform before, and one which he never recorded commercially. He often spoke of playing and recording the sonata with Horowitz but it never came to pass (they did record Brahms Sonata no.3 in D minor for RCA). Although it is true that many of his musical ideas for the Franck were unusual and very different from what most of us were accustomed to, here was an octogenarian playing a work he had not performed publicly for more than 40 years, experimenting with new and refreshing ideas, not all of which worked. It was the child in Milstein that kept him eternally young, in his playing and all throughout his life. He was constantly toying with new fingerings and bowings, experimenting with new ideas, inventing, composing, making jokes, fantasising about being a politician or a conductor, most of whom he despised, and helping young aspiring concert violinists.

Nathan Milstein will never be replaced. He stood alone on the highest artistic and technical plateaus and was cherished by those who knew him and who understood his great art. Although he was never to achieve the household fame of Heifetz in America, in part because he shunned publicity, he was highly revered and considered to be the ‘King of Violinists’ in Europe. He was, without question, Heifetz’s equal as a violinist, and in my opinion surpassed him as a musical intellect. He has been eternalised by his legacy of recordings. Just listen to the phenomenal Capitol recordings of the concerti of Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Dvořák, Glazunov, Goldmark, Lalo, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Prokofiev, Saint-Saëns and Tchaikovsky, and the charming recordings of vignettes, masterpieces and encores. These performances are unequalled, and I am delighted that many of these recordings have once again surfaced on CD. Perhaps one of the most dazzling displays ever of sheer violin virtuosity is Milstein’s first commercial recording of his own Paganiniana. It is truly a marvel, and for those who would suggest that he did not have an exciting temperament or that he lacked passion, listen to this set of variations he composed utilising several Caprices and other works of Paganini.

Milstein took America by storm with his performance of the Glazunov Concerto in Philadelphia in 1929, setting an almost unattainable standard of violin playing that he shared with his adoring public for over half a century. As is customary following the death of a great musician and artist, the recording companies released many of his long-deleted recordings on CD, including many of the Columbia 78s and early RCA LPs. Two Library of Congress recitals from 1946 and 1953 were released and they are extraordinary examples of a master violinist in his absolute prime.

There have been numerous tributes and memorials since his death 32 years ago, but the greatest tribute of all that could be paid to Milstein would be for aspiring and established concert violinists to listen to and carefully study his great art and to carry on the tradition of this violinistic and musical giant, one of the greatest violinists of all time.

Robert Levin is an arts consultant and manager with more than 40 years of experience in the performing arts in the areas of PR, artist, concert and orchestral management.

Watch: Nathan Milstein: Beethoven Violin Sonata no.9, ‘Kreutzer’

Listen: Nathan Milstein performs his own Paganiniana

Read: ‘I just try not to spoil it’ – Nathan Milstein on Bach

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

1 Readers' comment