Pablo Casals’s musical commitment and Daniil Shafran’s ease and freedom were sources of inspiration for the British cellist

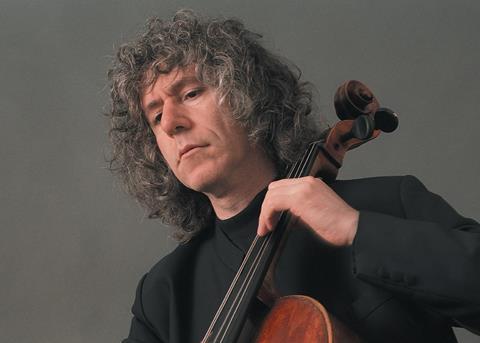

For Isserlis, Pablo Casals’s sound conveys what he has to say © Tom Miller

I USED TO LISTEN TO recordings of the Schumann Cello Concerto but I could never understand it or remember any of it. And then I heard Pablo Casals’s recording and suddenly I could remember it and it made sense. I play it differently myself, of course, but that’s how it should be. His performance is extraordinary. Casals thought like a composer, somehow: he understood the structure of the music and of each phrase. The commitment with which he played every note is astonishing. He obviously studied the scores deeply. He was a conductor, a pianist, a composer: an all-round musician. It wasn’t just about cello, it was about music. He had the ability to see into the heart of the works he played. He thought about everything, took nothing for granted and didn’t ever imitate. His conducting could be wonderful, too – his Mendelssohn ‘Italian’ Symphony with the Marlboro Festival Orchestra, for example.

Anyone who says Casals didn’t have a good technique doesn’t know what they’re talking about. There are some slips in live recordings from when he was over 80 – but even these are still incredibly good. And some of the earlier recordings are simply astonishing. People say that recordings don’t do justice to his sound – it’s true that it can sound quite dry. That doesn’t matter to me. Today it’s like a disease: people think that every note has to be beautiful, which is like saying that when we talk every syllable has to be beautiful and expressive. That’s not the point – it’s what we’re saying that matters. His sound conveys what he has to say.

Casals’s Dvorák is wonderful and his Bach Suites are also great, of course. They were a complete revelation at the time and have stood the test of time amazingly well. But if I had to take one composer played by Casals to a desert island it would be Beethoven, for the amazing strength and conviction of the playing. Integrity is key: nothing is for effect or to please the audience. His sole aim is to convey the truth about the music.

Daniil Shafran was for me like a Russian folk singer. I love the ease and freedom of his playing. When he was off he was really off, but when he was at his best, the freedom and joy of music making was incredible. He played straight from the heart – completely sincere music making. His playing is not to everybody’s taste, but then maybe people who don’t like it haven’t heard him at his best. He wasn’t trying to make a career, he was playing the way he had to. Although they’re incredibly different, that’s true of both Casals and Shafran. They couldn’t play in any other way than the way they played. They didn’t modify it to suit anyone else’s taste.

SHAFRAN HAD AN AMAZING TECHNIQUE – nothing sounds hard for him. It’s as if he was born playing the cello, making music. The elasticity of his bowing was extraordinary. The way his bow could dance was wonderful and some special effects, such as his up- and down-bow staccatos, were breathtaking. He did practise – too much, perhaps – but when you heard him play it was like he shouldn’t have had to practise at all.

I first met Shafran when I interviewed him for The Strad in 1987, and then I got to meet him again when Olli Mustonen and I sponsored his return to the Wigmore Hall – his first concert in London for 30 years. There was no arguing with him. Through his agent, he suggested a programme for that concert – Franck, Brahms and Shostakovich sonatas; I thought that perhaps he should play more Russian music so people could hear him at his very strongest. I put this to him and had some correspondence with his agent; it went round in circles, with various messages going back and forth. Then eventually I got a final message: ‘Mr Shafran has come up with a new idea which he hopes you’ll like – Franck, Brahms and Shostakovich.’ And that was that.

When I heard him live the sonatas were extreme – I loved them, but even I had to admit that they were controversial – but the encores were just perfect. Some of his playing became excessive in his later years, perhaps because he was somewhat cut off – he wasn’t that successful in his lifetime. He didn’t get to travel or to play with many great conductors or chamber music with great musicians. If he had, maybe he would have developed a bit differently. When he played that concert at the Wigmore Hall, I sat next to Sebastian Comberti, the cellist who runs Cello Classics; he loved the concert, because he said that it was like discovering the last member of a lost tribe of cellists. Where most cellists have four fingers and a thumb, Shafran had five fingers – the thumb was just one of them. I remember saying to him at the meal after the concert, ‘Tomorrow morning every cellist that was here tonight is going to wake up thinking they’ve got another finger.’ He replied, ‘Well, God gave us five fingers, so we should use them.’ It was strange to watch, but one didn’t really think about technique when one watched him. He was a force of nature.

THE LAST TIME I EVER SAW HIM he came to dinner before his second Wigmore Hall recital, and my wife Pauline cooked for him. It was very exciting despite the language barrier. When he wanted to go we called a cab. He asked me whether the taxi driver would speak German; I told him I didn’t think so. When the taxi driver came to the door, Shafran asked him: ‘Sprechen sie Deutsch?’ ‘Ein bischen,’ replied the driver. Shafran looked at me with such scorn – fancy me doubting that a London cab driver would speak German! And off they went into the night.

There’s a wonderful recording of him playing Beethoven’s A major Sonata with Carlo Zecchi, and some other marvellous recordings of standard repertoire (the Dvorák Concerto with Neeme Järvi, for instance). But perhaps Shafran was really at his most unique in Russian music, and in short pieces. I chose the repertoire for the Cello Classics reissue, which included the Prokofiev Symphony–Concerto (which is extraordinary), Kabalevsky’s Concerto no.2 (which he makes sound like a masterpiece), three pieces by Tchaikovsky (which are gorgeous) and some other little pieces. You can recognise him in three notes – he’d found his own voice, just as Casals had.

I often advise students not to listen to a piece they’re studying being played by anyone else: why talk to a vicar when you can talk straight to God? But most of them do listen to recordings, of course. Well, fair enough, perhaps – maybe it’s inspiring; but one should gradually try to free oneself of outside influences. One should never imitate. I never copied Casals but I did go through a stage of imitating Shafran the whole time. It was dangerous and I cured myself – although if people who know Shafran’s playing hear me playing Russian music they can instantly tell that I love him. It’s too easy to imitate him and one shouldn’t. But one can learn from the freedom, the ease and the refusal to follow clichés or to play like anyone else.

This article was published in The Strad’s Cello Heroes special. To subscribe click here.

No comments yet