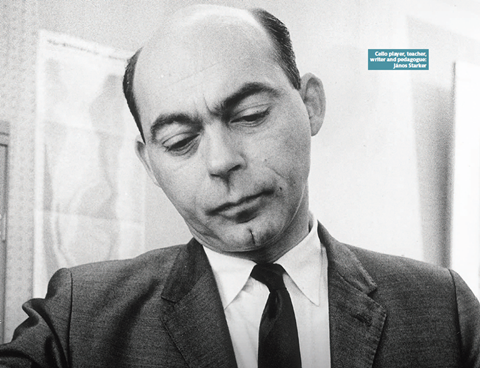

2024 marks the centenary of the legendary cellist János Starker. Helga Winold shares her memories of Starker, in this tribute from the April 2014 issue of The Strad

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

I first met János Starker in 1962. I’d just graduated from the Hochschule für Musik in Cologne but I felt I was struggling: I would practise for two hours before going on stage, just to make sure I was warmed up. Starker came to Düsseldorf for an extended masterclass that lasted four days, and I thought: this man has the solutions I need. He had the ideas about technique that I was looking for, that could free me up to do what I wanted to do more easily. I enrolled at Indiana University the next year.

Starker was incredibly demanding, both of his students and of himself. As a young teacher he would point out any weakness or flaw without mercy. He was convinced he could solve any problem, and he had lots of fun doing so – and he expected us to find solutions the same way he did. As he got older he became more encouraging and would acknowledge some of the things you got right.

He saw himself as a scientist–teacher. He came to the psychology lab when I was working there, and participated in trials to study bow-arm movement. He showed how we could anticipate our next movement while controlling the sound we were making, and observe the tension and release inherent in every movement and every joint of the body. He related musical emphasis to everyday speech. He would demonstrate that just slightly lifting your head before it comes down on an emphasised note helps to free the weight of the bow arm.

I joined the IU faculty in 1969 and frequently taught his classes when he was away performing. Although he was a man of few words, he would always say that his students had made great progress: ‘You’ve worked them right!’ He’d never go overboard with enthusiasm, but coming from him it was a great compliment.

Performing with him, I found him very encouraging – he never put on airs, wasn’t tyrannical, and seemed as if he was just having fun. When he recorded his tribute to David Popper, he recorded one extremely difficult piece after another, usually just in one or two takes – and in between he’d be talking freely, encouraging the pianist, asking listeners what they thought. There was only joy in the air! I don’t know why he invited me to come and listen, as there were very few people there – maybe he just liked to have an audience.

Each year he would honour one or two cellists – not just the well-known ones but anyone he felt had done something to ‘strengthen the cause’, as he put it. They would be named ‘Chevalier du Violoncelle’ or ‘Grande Dame du Violoncelle’, signed by the president, the dean and Starker. There would also be masterclasses for the students and then Starker would host a party for up to 50 cellists.

Even after he became too ill to leave his house, he continued to teach students. He constantly wanted to pass on his advice to other players, both students and teachers.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

Read: Memories of János Starker 1924–2013

Watch: János Starker: King of Cellists

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet