In anticipation of his tour playing in UK cinemas, violist and filmmaker Hugo Max reflects on his unique process of improvising live soundtracks for silent horror movies on solo viola

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

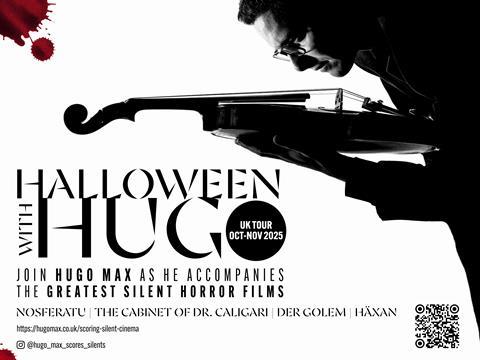

During the last three years I have performed live improvised scores to silent films on solo viola, accompanying regular screenings at the Prince Charles Cinema in London’s West End and in collaboration with Picturehouse Cinemas. This autumn I will present my third nationwide tour soundtracking four dark and imaginative works from the 1920s at some of the UK’s oldest and most beloved cinemas.

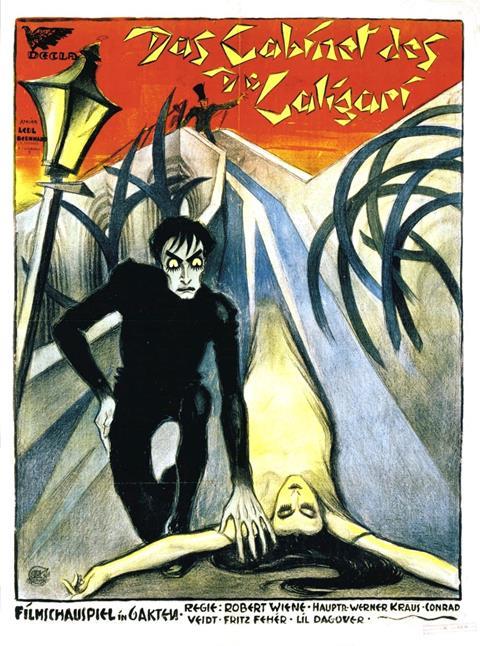

The featured films include three classics of German expressionism, Nosferatu (1922), The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Der Golem (1920), as well as the shocking Häxan (1922). Preparing for these performances has encouraged me to reflect on the contemporary resonances of these films and consider how improvisation has enhanced my relationship with my instrument.

I performed my first improvised soundtrack alongside Nosferatu in its centenary year. Around this time I had been filming a personal project at the Prince Charles Cinema depicting arts spaces silenced during the pandemic. The venue had not programmed a silent film with live music for some time and invited me to accompany two screenings of F. W. Murnau’s unauthorised Dracula adaptation. These performances heralded a rewarding creative relationship, returning to the cinema seasonally to soundtrack a variety of silent films on the viola, an instrument not traditionally associated with this craft.

Classically trained as a violinist from the age of four, I picked up the viola to broaden my experience of chamber music making. Free from the strictures of institutional learning, my relationship with this instrument has always been more exploratory than my engagement with the violin.

It was during the pandemic that I became focused on experimenting with viola improvisation, incorporating this creative process into my practice and performances which enabled me to hone my craft free from the tensions that I had previously encountered, developing a greater understanding of the connections between my music making, filmmaking and painting.

I am drawn to the viola’s dynamic melodic capacity and textural percussiveness, its conversational and dramatic responsibilities within the string family which make it well suited to respond to the visual language of silent cinema, particularly expressionist films.

My viola soundtracks were initially inspired by a formative experience rehearsing and performing Arnold Schoenberg’s Third String Quartet in my mid-teens. Writing on his influences for the first movement, the composer references the fairytale Das Gespensterschiff (The Ghostship) and its impact on his creative imagination, not as programmatic material but a ‘very gruesome premonition’ that incited the work.

The visceral tableau of a ‘captain nailed through the head to the topmast by his rebellious crew’ seems right out of the nightmarish imagery of expressionist horror. Schoenberg’s quartet was first performed in 1927, around the same time as some of the most striking German expressionist films were emerging. These films were born of similar creative concerns to those that underpin Schoenberg’s music.

My accompaniments pay homage to both expressionist music and painting, attempting to evoke the textures of Egon Schiele’s mottled bodies and Chaïm Soutine’s impasto beef carcasses, and also reference klezmer fiddle, exploring my own Germanic–Jewish ancestry.

Directors such as F. W. Murnau, Paul Wegener and Robert Wiene established the genre conventions of horror cinema as we now recognise them, crafting disturbed narratives that dissected contemporaneous fears and which remain relevant today: Nosferatu, with its themes of plague and otherness, captures the zeitgeist of a post-pandemic, identity-driven world; Der Golem retells the Frankenstein narrative as spurred on by Jewish mysticism and antisemitism; Caligari mourns the soldiers sent to kill and be killed on the First World War’s battlefields.

While my viola soundtracks draw on a variety of musical references, I do not seek to enforce a specific reading of the films, rather ask questions about their context. In contrast to the more unsettling works showing this autumn in time for Hallowe’en, I have also accompanied feature films by Buster Keaton that call for a different musical approach. The viola becomes the voice of Buster, at humorous and surreal odds with the kaleidoscopic world around him.

Scoring silent cinema is physically demanding yet always rewarding, requiring a sense of responsibility akin to adhering to the desires of a composer. Here I must serve the purpose of the film and the lives of its characters while remaining in direct communication with our audience. It is a pleasure watching these early cinematic works intensely while preparing to soundtrack them, memorising their rhythms, chiaroscuro images and astounding effects.

In the run-up to a screening I devise original ‘leitmotifs’ employed differently in each performance. In the case of scoring expressionist horror, the deconstruction of musical motifs over the duration of a film mirrors the breakdown of an on-screen character’s psychological state. I incorporate percussion provoked by bowed and plucked gestures as an extension of the viola’s sound world. My viola was made by Luigi Azzola in 1920 and I find it appropriate to accompany the preserved actions of the actors on screen with an instrument crafted at the same time.

I am looking forward to returning to the Prince Charles Cinema and Picturehouses this autumn while developing new relationships with cinemas across the country and expanding my repertoire of films. The tour is as much a celebration of the enduring power of these films as of the venues where I will be performing. Several of the cinemas date back to the 1910s and local communities have gone to great lengths to retain and restore these beautiful buildings.

Live soundtracks provide an opportunity to welcome audiences of all ages into these spaces notwithstanding the challenges posed by online streaming. I am delighted when audience members ask me questions about my musical process afterwards, especially as regular cinemagoers might not have ever attended an hour-and-a-half solo viola recital. With silent classics receiving updated restorations and films which were once thought lost being rediscovered and distributed, there could be no better time to delve into silent cinema.

Explore the full programme and book tickets at: https://hugomax.co.uk/upcoming-performances

Read: The epic film scores of John Williams, arranged for flute, cello and piano: cellist Cécilia Tsan

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet