Despite losing the function of the third and fourth fingers of his left hand through focal dystonia and a shoulder injury, violinist Clayton Haslop was determined to continue playing. Here he shares his story

The following is an extract from an article by Clayton Haslop in The Strad’s January 2021 issue. To read in full, click hereto subscribe and login. The January 2021 digital magazine and print editionare on sale now.

The first indication was a strange misplacement when I attempted to play a whole step between my second and third fingers. Without a concerted effort, my ring finger curled to the side as it followed the second finger to the string. Every other hand movement was normal. Initially, a little forethought provided an adequate workaround: ‘Remember to think ahead, keep that finger relaxed, and you can control it.’

Read: Two-fingered Tchaikovsky: Beating the odds

Watch: Interview with two-fingered violinist Clayton Haslop

Watch: Two fingered violinist plays Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto

It was about the time that I realised that this strategy was at play all too frequently, and that I was altering my fingering choices in an attempt to avoid ‘an issue’, that the dreaded words ‘focal dystonia’ came to mind. Mind you, this was happening 25 years ago, when there wasn’t much talk about the condition in musical circles, and many musicians suffered in silence while seeking dubious ‘cures’ from the most unlikely sources (more on this later). Identified many years ago as a neurological condition affecting a muscle or group of muscles in a specific part of the body and causing involuntary movements, focal dystonia is still not fully understood. My knowledge of the condition was limited to what I knew of the great American pianist Leon Fleisher. In 1964, aged 36, he was forced to retire from active concert life owing to its crippling effects on his right hand. It seemed a very rare condition, yet soon after my diagnosis I was to learn that as many as 12 to 14 per cent of people reliant on fast, repetitive movements of small muscles are eventually challenged by it: typists, vocalists (in the vocal cords), brass and woodwind players (the embouchure) – the list goes on.

As the months went by, it wasn’t just whole steps that troubled me. Half-steps became an issue, then 3rds, and finally, any call on my third finger carried a potential for embarrassment. Yet through creative practice strategies, sweat and what I refer to as ‘smoke and mirrors’ I managed to soldier on.

-

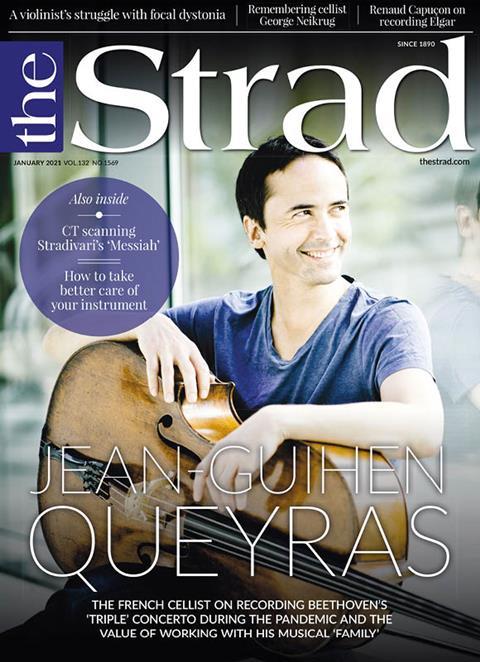

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue.Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more playing content here

1 Readers' comment