Hope speaks about Menuhin's influence on his life and career

The following is an extract from The Strad’s Memories of Menuhin article, featuring interviews with friends, family and colleagues of the great violinist and published in the May 2016 issue – download on desktop computer or through The Strad App.

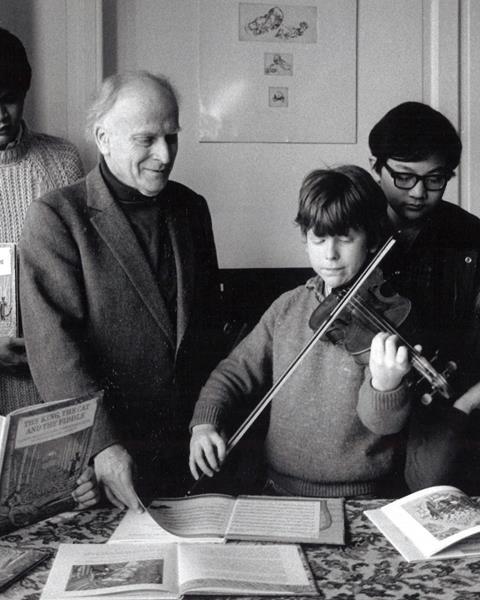

Yehudi Menuhin was the reason I became a violinist. Neither of my parents had a musical background, but my mother was Menuhin’s secretary for 24 years and my earliest memories are of being surrounded by music, particularly the violin – whether it was Menuhin playing or one of the many violinists who came to his house. He had a huge collection of musical memorabilia, including Paganini concert posters and portraits, and of course violins.

So when I announced, aged four, that I wanted to be a violinist, my parents weren’t all that surprised. I remember hearing artists such as Robert Donington and Mstislav Rostropovich at Menuhin’s houses – I even recall trying to pull Slava’s cello spike out from under him while he rehearsed. I heard Menuhin play alongside Stéphane Grappelli and Ravi Shankar, for whom he had huge admiration, particularly for their ability to improvise, something with which he struggled.

He was an inveterate learner as well as an inveterate teacher – constantly searching for answers to life and music. I encountered this side of him first hand after I’d started studying with Zakhar Bron. Menuhin wanted to know all about Bron’s teaching, and we talked for several hours, during which he asked me to play for hours – he’d jump in with fascinating insights, suggestions and comparisons.

While I was still studying with Bron, Menuhin said, ‘I can’t teach you myself because I don’t have the time; but if we go on the road together, I could coach you while we’re on tour.’ We gave around 60 concerts together and it was a very steep learning curve for me; I was the soloist while he conducted, and often he would literally instruct me on the concert platform.

During one performance of the Beethoven Concerto, he beckoned to me at the end of the first movement and whispered, ‘At the start of the second movement, try beginning on the D string, not the A string,’ and I had to work out the fingerings then and there. It was as if he was playing vicariously through me, trying the experiments he’d perhaps have made if he were the soloist. At the end of the concert he might say, ‘Well, that wasn’t the best idea, was it?’ But it meant that every concert was certainly special.

Menuhin would always try to let the student find their own voice, but there were certain things that he believed very strongly. If you played the solo entry at the start of the Brahms Concerto in a wayward manner, he’d definitely object. I don’t mean that it had to be metronomic, but if you pulled it about too much, he’d put his foot down. On the other hand, if you came up with spontaneous suggestions, that might fire his imagination and he’d come back with even more ideas. In that sense, he was the most original musician I’ve ever met.

The complete Memories of Menuhin article, featuring contributions from Menuhin's eldest daughter Zamira Menuhin Benthall, Menuhin School head of music Malcolm Singer, violinist Tasmin Little, Live Music Now founder Ian Stoutzker, Menuhin biographer Humphrey Burton, EMI Classics producer John Fraser and violin maker Joseph Curtin, is published in The Strad’s May 2016 issue. Click here to subscribe and login. Alternatively, download on desktop computer or through The Strad App.

View: Yehudi Menuhin's marked-up copy of Bach's Solo Violin Sonata no.2

Read: Violinist Yehudi Menuhin’s first appearance in The Strad, aged 10

No comments yet