Tully Potter reviews the second volume of memoirs by the Brodsky Quartet’s Paul Cassidy, in which he recalls his time with the foursome

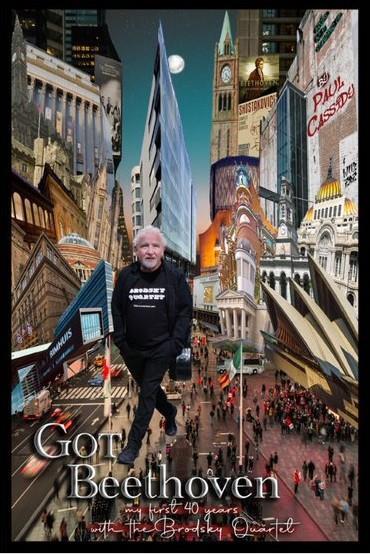

Got Beethoven: My First 40 Years with the Brodsky Quartet

Paul Cassidy

311PP ISBN 9781803130590

Troubador £12.99

This is the sequel to Get Beethoven!, Paul Cassidy’s account of growing up in Derry and taking his first steps in music (reviewed in February 2021). We are given to understand that now he is in the Brodsky Quartet, Beethoven is an integral part of his life, although far more space is given to the pop and rock stars with whom the Brodskys have been associated – I fear the endless parade of glittering names makes my eyes glaze over.

The Irish-boyo-in-a-pub style remains and our hero is both gullible and bereft of a good editor and checker. It does not instil confidence when, as early as Page XII, we are given a stream of dodgy, even daft, information about Adolph Brodsky, after whom the quartet was named. Zoltán Székely, never more than an excellent club tennis player, is said to have won Wimbledon – he is also traduced musically. A number of first and/or surnames are spelt wrong.

It is just as well Jessye Norman is dead, as she once sued someone for attaching to her the hoary old story retailed on page 73 – I first saw it told about Ernestine Schumann-Heink and it actually stems from a Victorian Punch cartoon of a fat woman getting on to a bus. A rant against Wigmore Hall on pages 126–7 is embarrassing to read and gains an element of farce when Cassidy mixes up his Bond villains – it is Blofeld, not Dr No, who constantly strokes a cat. If Cassidy ever mentions the surname of the Brodsky Quartet’s third leader, Daniel, I missed it (it is Rowland).

Fortunately there is solid sustenance and interest here, if you can winkle it out. On pages 76–79 Cassidy relates how the Brodskys’ relationships with Harrison Birtwistle and Maria João Pires were torpedoed by outside interests. On pages 84–5 are pithy observations comparing the way sports stars are featherbedded with the fates of musicians, mostly left to fend for themselves.

Travelling with four people seems to multiply the chance of a mishap, and there are plenty of good quartet stories here, such as the one where the group touched down at Bologna to find that when Jacqueline Thomas – the Brodsky cellist and Mrs Cassidy – opened her Stevenson flight case to check her instrument, it was in several pieces, bridge collapsed and fingerboard off. Both local BA representatives played the cello and could offer a temporary replacement. Another time, the Brodskys discovered that several of their instruments were coming apart, owing to the fearfully low humidity in the hall.

Cassidy is understandably proud of the out-of-the-way classical music he and his colleagues have recorded – I can personally vouch for their Respighi and I must seek out the Spanish pieces he mentions. They have not yet done a complete Beethoven cycle on record but have two sequences of the Shostakovich quartets under their belts – Cassidy once found himself sitting next to the composer’s widow Irina at dinner and, true to form, made sure he got a tip from her about interpretation.

Two of the Brodskys have been in place for half a century and Cassidy has completed four decades. On pages 224–5 we learn of the physical toll that playing the viola has exacted on the Cassidy frame but he leaves us saying: ‘I feel as motivated today as on that first visit to Manchester [for his audition].’ You cannot fault his enthusiasm. As before, the book is not illustrated but photos can be found at www.paulcassidy.org

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet