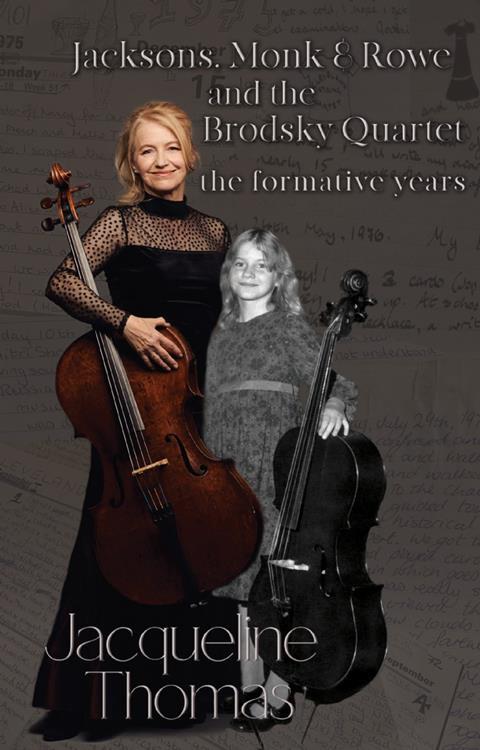

Tully Potter reviews the memoir of Jacqueline Thomas, cellist of the UK’s Brodsky Quartet for more than 50 years

Jacksons, Monk & Rowe and the Brodsky Quartet: The Formative Years

Jacqueline Thomas

328PP ISBN 9781803133096

MATADOR PUBLISHING £12.99

After two books by violist Paul Cassidy – one about his early life in Derry, the other detailing his 40 years in the Brodsky Quartet – here is his wife, cellist Jacqueline Thomas, to tell us about the first decade of the quartet’s half-century.

It is an astonishing tale and Thomas is surely right to claim primacy as the longest-serving female quartet cellist, although the group as a whole will have to keep going a while longer to beat the Panocha Quartet’s 54 years so far.

The tragic thing is – and Thomas makes this point several times – that in today’s UK with its philistine government, the conditions that created a string quartet with members aged 10 to 12 can never be repeated. You have only to hear a few editions of Desert Island Discs to notice the decline in music education standards.

The miracle took place in the seemingly unlikely location of Middlesbrough, the town on Teesside in North Yorkshire best known for its football. But music was well supported and the Thomas siblings who formed the top and bottom of the then Cleveland Quartet, Michael and Jacqueline, came up via the usual youth orchestra route.

Read: Book review: Get Beethoven!

Read: Book review: Got Beethoven: My First 40 Years with the Brodsky Quartet

Review: Brodsky Quartet: Homage to Bach

It was a riotous upbringing, with eight children plus a skeleton in the cupboard who revealed himself as an extra half-brother. Dad and Mam were almost over-supportive and the ‘Big House on the Corner’ rang with music from morning to night. One drawback was that Dad thought women could not be creative.

Thomas quotes copiously from her teenage diaries, some entries amounting to Too Much Information. Her opinion of Wolfgang Schneiderhan will make his admirers’ hair stand on end. As she grows musically, she encounters misogyny and abuse, especially at the Royal Northern College of Music.

The Cleveland Quartet metamorphoses into the Brodsky and goes through the hoops of competitions – she is wrong about the Portsmouth contest being the first one – and defections, although fellow founder Ian Belton still occupies the all-important second violin chair.

She and I could have good arguments about ‘democracy’ in quartet playing (sooner or later someone has to turn on some great violinism in Beethoven first violin parts), standing up to play and trying to straddle both pop and classical worlds. But no one could argue with her observations on listening within a quartet – and 50 years is a great record, however you look at it.

‘What is life without music?’ she asks. ‘Looking back on the experiences I had as a child – and so many like me – how can governments so callously make cuts and undervalue this most important art form?’ She might have added that a century of research has established how good music is for children’s development.

Her reproof to journalists about the meaning of ‘crescendo’ should be emblazoned across newsrooms and studios up and down the country. On the other hand, she is strangely vague about Henry Wood’s Sea Songs and appears not to know that noble song Tom Bowling (she should listen to Yorkshire’s Walter Widdop).

She clearly did not get on with that great musician Milan Škampa and there was no need to caricature his way of speaking. She misspells Grieg, composer Antony Hopkins and even the Monkees. She also over-uses adjectives – we do not need telling that Yehudi Menuhin’s career was ‘illustrious’.

Enough of quibbles. Her memoir is well illustrated with two sections of photographs on art paper and is mostly well written in a Molto vivace style. And that strange title for the book? ‘Jacksons, Monk & Rowe’ was a rather convoluted nickname bestowed in her childhood by Dad.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet