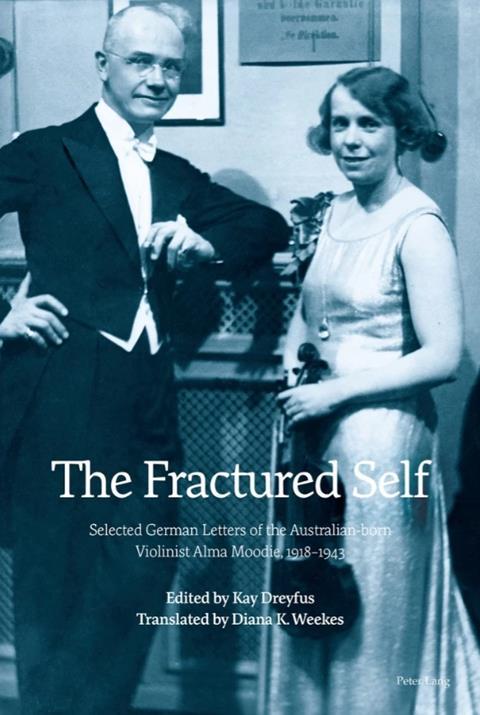

Tully Potter reviews a comprehensive collection of letters which cast light on the life and career of one of the early 20th century’s best known female violinists

The Fractured Self: Selected German Letters of the Australian-born Violinist Alma Moodie, 1918–1943

Ed. Kay Dreyfus

666PP ISBN 9781800790216

Peter Lang Verlag £55.60

This is the third time Australian academic Kay Dreyfus has sought to interest us in her compatriot, the German-based violinist Alma Moodie (1898–1943). I reviewed the second book, Bluebeard’s Bride, in 2014. The new volume is more ambitious: a selection of 268 letters which Moodie wrote mainly to the men in her life, including 136 of 200 she sent to the well-known Winterthur businessman, amateur clarinettist and patron Werner Reinhart.

With Reinhart she is more unbridled than with anyone else. She uses various pet names for him and is very candid, often being highly critical of such colleagues as the conductor Hermann Scherchen. Whether the intimacy with Reinhart had a sexual element is not known, but he gave her two violins, a Gofriller and a ‘del Gesù’.

How important was she? A favourite pupil of Flesch, she was a leading player in the German context yet left no recordings. She counted Kreisler and Rilke among her friends. She appeared with top orchestras and conductors and had a reputation for playing new music, although only Krenek – with whom she had a fling – Stravinsky, Wellesz, Bartók and Szymanowski were progressive.

A number of letters are addressed to the ultra-conservative Hans Pfitzner, whose Violin Concerto – the only one I know where the soloist is silent in the slow movement – she premiered and championed, giving more than 50 performances. She introduced Kurt Atterberg’s Concerto, with its lovely slow movement, to Germany.

Moodie had many things going for her, including a sonata duo with pianist–composer Eduard Erdmann, but marriage in 1927 to the lawyer Alexander Spengler did not work out well for her. He was a Nazi, uninterested in her career and unfaithful, but with two children Moodie must have felt trapped in Germany throughout the 1930s.

I find her a tangle of contradictions, a strange amalgam of the switched-on and the switched-off, making anti-Semitic remarks yet showing concern for Jewish friends; slagging someone off at one point and praising them at another; writing of moving to London, then railing at British bombing in May 1940, seemingly oblivious of what the Luftwaffe had already perpetrated in Spain; commenting adversely on conditions in Germany, then quoting the Führer approvingly.

Yet the letters have many fascinations, charting a highly musical, intelligent artist’s struggle to make a living, while her world was disintegrating around her. And there are innumerable felicities, such as lunch with the legendary baritone Battistini, ‘the only singer I know that violinists can learn from’, and Szigeti, a notorious string-snapper who managed to break his bridge in two in Prokofiev’s First Concerto.

Five essays expand the book’s reach: Erdmann recalls Moodie’s artistry; Birgit Saak writes about the duo; Goetz Richter considers Moodie’s relationship with Flesch; Peter Tregear deals with the Krenek connection; and Michael Haas chronicles her uneasy gradual capitulation to the Third Reich – in 1939 she joined the NSDAP so as to teach at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt.

The many photographs strangely do not include Spengler. There are copious endnotes but I would have liked to have some of that information in footnotes. Translator Weekes sometimes uses anachronistic words such as ‘toxic’, ‘uptight’ or ‘network’. Warts and all, Alma Moodie merits our attention.

TULLY POTTER

Read: Who was violinist Alma Moodie?

Read: Alma Moodie: From Praise to Obscurity

Book review: Pioneer Violin Virtuose in the Early Twentieth Century

No comments yet