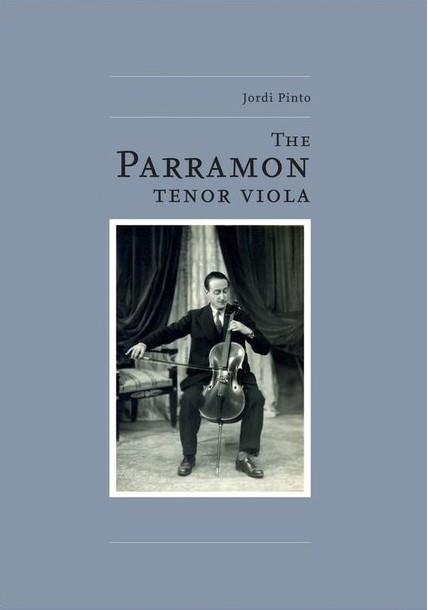

Philip Brown reviews Jordi Pinto’s book about an unusual instrument from the early 20th century

The Parramon Tenor Viola

Jordi Pinto

240PP ISBN 9788409425440

casa Parramon €150

I admit to not having known about the Parramon tenor viola before reading this excellent publication. In it, Jordi Pinto takes us on an exhaustive exploration of a little-known Catalan 20th-century phenomenon in a beautifully produced book on the topic.

In this treasure trove we learn about the enterprising Ramón Parramon i Castany (1880–1962), the cellist, maker and entrepreneur who ran a very successful shop employing top luthiers as well as representing the best German, English and French makers of the time. Parramon was ahead of the field in Spain, perhaps emulating the great businessman Vuillaume. His workshop created many fine instruments and founded an annual competition with a generous prize of a Parramon-made instrument. One gets the impression that Parramon created a workshop team that was better than the sum of its parts; that’s rare. Parramon was also a friend of Pablo Casals, who guided and supported him in his viola adventure.

A hundred years ago, the viola was trying to emerge from the shadows and had some illustrious champions such as William Primrose, Lionel Tertis and Paul Hindemith, so the territory was fertile ground for development and Parramon seized the challenge. The issue, as he saw it, was that the viola lacked the physical proportions to enable it to excel. He therefore created the Parramon tenor viola to make the viola into a truly soloistic instrument.

Parramon’s solution was an instrument with a large body (around 550mm) played sitting down like a cello, with a spike. The tuning remained the same. These instruments were met with some trepidation but gained ground quite quickly, with good numbers being made between 1932 and 1936.

Parramon used his competition to promote the new tenor viola. Concerts followed and in 1935 a well-received performance in Paris featured the instrument in a specially composed piece by Marius Casadesus: Barcelona Symphonic Poem. The book then gives details of concerts and a recording, with the future looking bright: 1936 seemed to be another breakthrough year, as other orchestras adopted or considered adopting the Parramon model. But later that year, with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Parramon went to live in exile, which sounded the death knell for his business. The onset of World War II was the final nail in the coffin. It’s sad these two conflicts robbed us of this promising addition to the string world, halting the widespread exposure and acceptance that Parramon’s invention perhaps deserved.

This book is created in sumptuous style: good paper, nicely bound, and very well laid out. There is a well-presented gallery of the violas and moulds; the photographs of the instruments are well lit and printed. The instruments themselves are a very attractive Amati/Stradivari melange with the clean, crisp workmanship one usually associates with French instruments – although unlike those, they were finished in an even, deep amber-coloured thick varnish, giving a hint of the late Italian school.

Pinto has structured this book very well, from putting the instrument in context through to its creation and the clever promotion that Parramon executed. Details of the instruments, a gallery section and plenty of interesting adverts and ephemera adorn the text. He can rest assured that he has done the subject justice. In short, Pinto has created a marvellous and intriguing archive – one that will be valued for many years.

PHILIP BROWN

No comments yet