Christian Lloyd reads Ernesto de Angelis’s treatise on Neapolitan lutherie, now translated into English for the first time

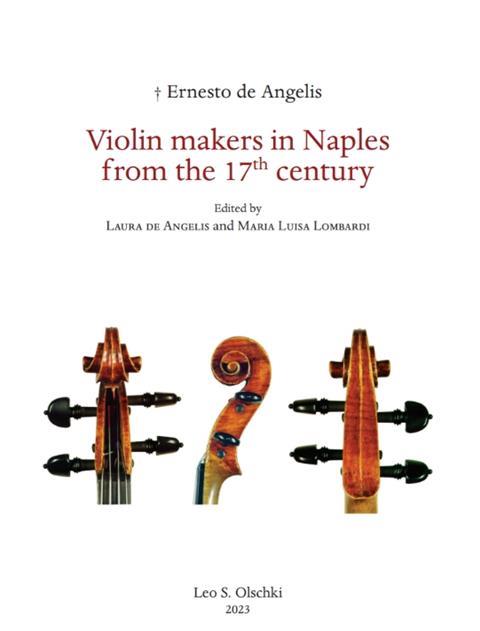

Violin Makers in Naples from the 17th Century

Ernesto de Angelis

82PP ISBN 9788822268686

CASA EDITRICE LEO S. OLSCHKI €25

It is 15 years since Ernesto de Angelis’s book on the Neapolitan luthiers first appeared, and it is still the only volume available on the subject. Now it has been translated into English, and a wider audience can appreciate the scholarship of this devotee of the Neapolitan making traditions.

De Angelis (1943–2001) was a doctor, biologist and ‘amateur violin maker’, as he liked to call himself. He spent much of his life researching the lives and instruments of the Neapolitan makers, and after his death the notes he made and his collection of instrument photos were collected together and edited into a book. It is divided into three parts: an introduction to the history of violin making in Naples and notes on the distinguishing characteristics of the Neapolitan making school; biographical information on around 50 luthiers of the 19th and early 20th centuries; and finally, a photographic record of 38 representative instruments by the various makers. For each instrument (27 violins, 6 violas, 4 cellos and 1 double bass), the date is given as well as its principal dimensions and details of the label. All the photos were taken by the author, often while he was restoring the instrument at his workbench. Consequently, the whole book has a sense of authority, as De Angelis is clearly writing with a broad hands-on knowledge of the Neapolitan makers and their traditions.

The first section is probably the most useful to today’s makers, as it includes a summary of the main characteristics of the ‘Neapolitan school of lutherie’. De Angelis summarises the most important ones at the end of the chapter: ‘the heavy thickness of the tables, the protruding points, the rather flat back, the scroll with its protruding first volute and the lower placement of the eye, the nearly vertical positioning of the f-holes, the thin purfling [and] the transparent oil varnish, yellow–brown or red–brown’. There are many more, and his descriptions are often colourful: ‘the lower bouts are rather flat at the bottom, giving the impression of a “sitting” instrument’, and ‘the first volute is more protruding so the scroll appears to have ears’. De Angelis’s biographies of the various makers are also filled with commentary that suggests he knew them personally: for instance, we learn that Giuseppe Cappiello (1922–92) was ‘known to offer lunch to anyone who went to see him for minor violin repairs or just to see his violins’. The lively prose style makes this volume one of the most enjoyable books on lutherie I have recently read.

Read: The gain in Spain: German makers in Naples

Read: From the Archive: a cello by Gennaro Gagliano of Naples

It is odd, then, that among so much first-hand scholarship, De Angelis tells us on page 4 that Alessandro Gagliano ‘was a student of Antonio Stradivari’, even though 18 pages later he backtracks and says he was ‘a possible pupil of Stradivari’, but two pages after that, that he ‘worked about 30 years in the Stradivari workshop’. There are also some odd translations (‘People says that Pistucci is also know to letting play his just finished violins to poor people’) but these are minor quibbles about a book that will prove very valuable for luthiers, scholars and researchers into the making traditions of southern Italy’s largest city.

CHRISTIAN LLOYD

No comments yet