A fitting 150th-birthday tribute to a musical visionary

The Strad Issue: November 2024

Description: A fitting 150th-birthday tribute to a musical visionary

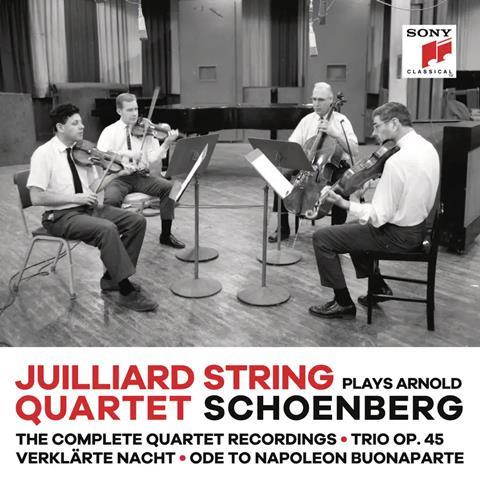

Musicians: Juilliard Quartet, Glenn Gould (piano) John Horton (reciter) Uta Graf, Benita Valente (soprano) Walter Trampler (viola) Yo-Yo Ma (cello)

Works: Schoenberg: String Quartets nos.1–4 (1953 and 1977 cycles); String Quartet in D major; String Trio (1966 and 1955), Ode to Napoleon, Verklärte Nacht

Catalogue number: SONY CLASSICAL 19658827202 (7 CDs)

Schoenberg wrote his cycle of four ‘official quartets’ over the course of three decades, between 1905 and 1936. During that time, music and art and the rest of the world changed forever. More than any other single body of work, I think, these four quartets illustrate the inner necessity of modernist principles in music – and the evolving quality of Schoenberg’s mind. Add the unpublished quartet of 1897, and the String Trio of 1946, and the picture becomes still more complete.

For years – to the first postwar generation of listeners, maybe the second too – the Juilliard Quartet held sway in this music, and even defined it in the ears of its public. Even if European ensembles of the time had the technique to master Schoenberg’s fusion of traditional form and counterpoint with modern harmony, most of them lacked the enthusiasm to do so. The 1953 cycle set down a marker of accuracy and authority, and it still stands up well in this newly remastered collection.

Schoenberg had died just two years earlier, and the set had a documentary value at a time when the privately recorded cycle by the Kolisch Quartet, dating from 1936–7, was largely unknown and (to all intents and purposes) unavailable. In the Juilliard’s reading there’s a nervous energy coursing through the first movement of the Third Quartet. The notes are all there, and even now it retains an insistent, sometimes strident sense of novelty.

The booklet reprints an interview from the later, 1977 set, in which Robert Mann (the only player common to both versions) recalls playing the First Quartet to Schoenberg. The composer said: ‘You know, you played it in a way that I’d never conceived it. You play it so wonderfully this way, and I like it – I want you to continue playing it this way!’ Later, a Schoenberg disciple confided that ‘Mr Schoenberg thinks you’re wonderful, but I have a feeling he might prefer if you wouldn’t play quite so intensely.’

By a curious quirk of discographic fate, the later Juilliard cycle is much less well known, and is only now receiving its first digital transfer. The architecture is largely unchanged, but there is a gain in familiarity and experience at knotty points such as that opening movement of the Third. It took later and more European-adjacent performers to bring back to the Third and Fourth a sense of their place at the end of the Austro-German canon initiated by Haydn.

As Ilya Gringolts and his colleagues on BIS have demonstrated, it is possible to find in the scherzo movements of the Second and the Fourth a playful humour which was foreign to Mann and his colleagues. Such a comment should not be taken to imply a harsh or unyielding approach. In both Juilliard versions, the First Quartet is especially impressive, both energetic and expansive in a way that measures up to the piece’s scale and ambition, never losing either focus or momentum over its 40-minute span and culminating in a coda of elegiac strength and repose. Schoenberg’s achievement here is all the more remarkable when heard in the context of the 1897 piece with its Dvořákian accents and the merest glimpses of the Schoenberg to come, in the angular shape and sometimes laboured academicism of the theme-and-variation slow movement.

Yo-Yo Ma and Walter Trampler contribute to an Impressionistically sensuous but restrained Verklärte Nacht, very much ‘late’ Juilliard and standing at one remove both from the up-front character of the earlier quartet sets and from the conventional presentation of the piece as an apotheosis of supercharged late Romanticism. From the other end of Schoenberg’s life, the Juilliard also recorded two works fusing tonality and 12-tone technique in the composer’s direct response to life and its vicissitudes: his ill health in the String Trio and his vituperative rejection of tyranny in the Ode to Napoleon. Between the early and late versions of the Trio there is little to choose save for the less immediate but more accommodating digital-era studio engineering.

‘Klarheit uber alles’ – ‘Clarity above all!’ – was Schoenberg’s appeal to his musicians, at a time when fidelity and dedication were of primary concern. This set may not present the last word on any of these pieces, but it honours his memory just as the changing members of the Juilliard did over the course of more than half a century.

PETER QUANTRILL

No comments yet