Ariane Todes is impressed by the openness of luthiers at the makers' workshops in Oberlin

String players might know the sleepy little university town of

Oberlin, Ohio, for its conservatoire. Little do they know that

during the summer months, some of the top violin and bow makers

around the country, and the world, migrate with their workbenches

to the art studios there, with one main aspiration: knowledge. And

I’m just back from my trip there with the same objective, for an

article for our November issue.

The principle is simple – put people who know something about

something in violin or bow making in a room together, give them a

project to work on, and watch how the overall knowledge of the

system increases exponentially, whether it’s relatively novice

makers or senior members of the community discovering new ways to

hold a gouge or learning about modal analysis. It’s not surprising

that this hotbed of research and sharing has been widely credited

for the healthy state of violin making today.

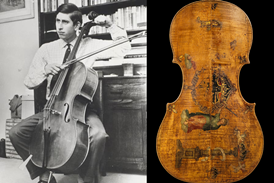

There are sessions to attend (a particularly popular one being the

slideshow of CT scans of top instruments showing enough intimate

detail to have the crowd salivating), alongside the group project

of working on copies of the ‘Betts’ Stradivari or a Tourte bow. The

most heated and revelatory discussions often seemed to happen over

breakfast, at the communal cooking sessions, or during a 1am break

outside the studio. Many times I felt truly awed by the profundity

of violin geekdom here, and by the way each luthier has their very

own specific emphasis in their work and their obsession for

instruments, be it acoustical measurement, purfling, wood density,

varnish, or finding the perfect stones with which to antique

instruments.

One of the questions we debated over breakfast was how today’s

violin makers can market themselves to get beyond the popular

appeal of Stradivari and his friends. As I left, my mind buzzing

with new information about violin making and a renewed sense of

respect for the commitment of these makers, I wondered whether the

answer is right there in Oberlin. If players could see and

experience first hand some of the passion and expertise that goes

into creating instruments, and learn the fundamentals of what

luthiers try to achieve, whether acoustically, technically or

aesthetically, would they be more likely to believe in the

possibilities of modern instruments?

Oberlin’s success lies in opening up a circle of knowledge where

once people would have been excluded and secrets kept. For all the

conventions and makers’ days I’ve been to, I’ve never yet come

across a place where players are truly included in this circle and

I wonder if this could ever be practical. Maybe it’s time that

players did know about what goes on in Oberlin after

all.

Find out more about the Oberlin workshops in the November 2012

issue of The Strad, available to download

here.

No comments yet