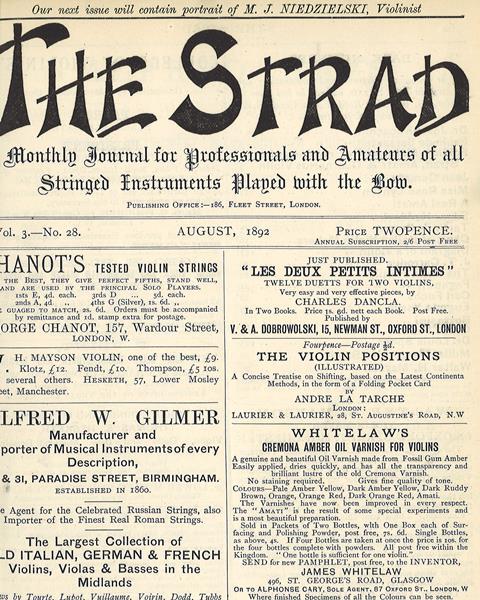

An article from The Strad, August 1892, exhorts lazy amateur violinists to work harder – especially female ones

Though not a violinist myself, there is no instrument which appeals to me so much as the violin; its grace, its frailty and its poetic sensitiveness make it the highest of all instruments, and therefore it is the most difficult instrument of all others to play well. Yet it seems to me that the number of amateur violinists is increasing, and I venture to say that this is by no means an unmixed good. Who has not suffered from the effects of bad violin playing? It is indeed the keenest of mental suffering to listen to some of the amateur performances in private drawing-rooms and in concerts for the poor; and it is a vast mistake to suppose that the poor do not know the difference between good and bad music. At one of our well-known institutions a lady offered to perform to some old women in one of the wards. “What would you like me to sing?” asked the lady. And the old dame replied, “Ask her” (pointing to another inmate), “she’s the one that suffers the most from music.”

Why should not the amateur violinist be as conscientious as the professional artist, and never perform a composition, however simple, unless he or she is capable of playing it in tune and time? I have heard some excellent orchestral playing by amateurs under the directorship of a great violinist, and with the assistance of a great pianist, whose genius and marvellous artistic rendering of the work performed must have inspired every member of the orchestra, and it seems to me that in combined effort, amateur work has risen to a high standpoint.

Not for a moment do I deny the excellence of some amateur solo players. I know well that many amateur violinists play far better than some professionals, who are toiling hard all day long, and have little time to practice and to devote to the art they love. Possibly the same maybe be said of the amateur who is so occupied with his business during the day that he comes home too tired at night to study. There are great amateurs of both sexes, and I honour them, but it is not of them that I speak when I say that there is a class of amateur which should be made to rouse itself. The people of this class are of both sexes, and their laziness is one of the most deplorable things to see. I regret to say that they are principally of the fair sex – the young lady who takes a few lessons, who is the cause of infinite vexation to her professor and to her parents, and who, when she is asked to play begins by saying she is really too nervous and then treats the company to one of the most diabolical performances it is possible to conceive. In the first place, she generally selects a composition which she has not attempted to master and which her professor has often told her requires many hours of hard study, and in the second place, she plays out of all tune and time. If this young lady would devote some of her leisure hours to real study, she would be able to give a great deal of pleasure instead of pain.

In conclusion, I would add that the work of the amateur violinist is full of grand possibilities, and that by earnest labour and reverence for the great souls whose work he wishes to interpret, he will lay a worthy tribute at the shrine of Art.

T.L.

First published in The Strad, August 1892. Subscribe to the magazine here.

No comments yet