The private residence where some of the legendary players featured in the October issue of The Strad performed is under threat. Nicholas Lane revisits those glorious days – and nights – via first-hand accounts from the time

Casals, Ysaÿe, Thibaud, Tertis, Sammons, Goossens, Suggia, Kocha?ski, Rubinstein, Cortot, Stravinsky, Nijinsky, Szymanowski and many more.

‘So through the season of 1912–13 it went. No visiting musician left London without being brought to Edith Grove, and it went without saying that those who came to give concerts would come to us afterward.’ So wrote Muriel Draper (1886–1952) in Music at Midnight, her entertaining account of this extraordinary episode in musical history published by William Heinemann, London, in 1929.

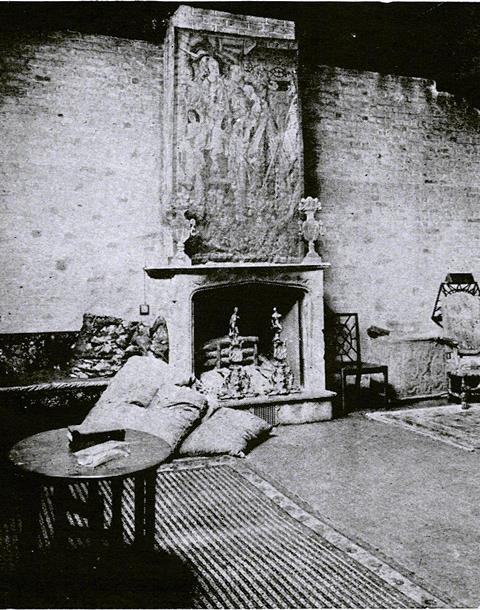

There can be few domestic studios where so many great artists from all over the world have come together to play under one roof. That the very same roof at 19a Edith Grove in Chelsea, London, still exists today and remains unaltered a century later is something of a miracle, having survived the bombing during the Second World War of number 19, the house which stood just a few feet in front of it, and subsequent threats to demolish it. The present freeholders are planning a major refurbishment that will involve the replacement of much of the timber roof, which is likely to be boarded in thus destroying the acoustic properties of the room. The parquet floor is to be dug up, the walls insulated, the windows replaced – almost nothing of the historic fabric will remain.

During the summer of 1912 numbers 19 (built c.1864) and 19a Edith Grove became the home of the American tenor Paul Draper (1886–1925) and his wife Muriel. Number 19a, the studio in the garden, was the reason they chose the house. They had moved from Florence to London the previous year at the suggestion of the pianist and violist Harold Bauer, in order that Paul Draper could study singing with ‘the greatest teacher of German lieder alive’, Raimund von Zur Muhlen (1854–1931), a personal friend of Brahms and Clara Schumann. He had emigrated to England in 1907.

English artist and illustrator Walter Crane’s former studio in Holland Street, just off Kensington Church Street, stood opposite Zur Muhlen’s London residence. It became the Drapers’ first home when they moved London. It was through Montague Vert Chester, a concert manager of repute, that the Drapers began to meet the musical elite of the day and to invite them back to their home. The October 1911 season brought Thibaud to London and Casals was on his way. Chester had cautioned them not miss the debut of a young Polish pianist, Artur Rubinstein.

Muriel recounted in Music at Midnight: ‘The nucleus formed by Rubinstein, Thibaud, Bauer and Draper proved magnetic’. Casals was scheduled for a concert at Bechstein Hall (now Wigmore Hall) and was eager to meet them.

Muriel’s unstoppable impetuosity brought about the magic of the following years. One senses from her writings that it was driven above all by a genuine and impassioned love of music. She also had an uncanny insight into the workings of the artistic mind:

‘I have noticed with musical artists that a concert acts as a preliminary stimulus, and that granted the conditions, they can go on playing until dawn. Knowing that the only reason people are listening is because they desire it, and that the taste and musical knowledge of fellow-players enable them to give and take every phrase at full value, brings a pleasure to such spontaneous exercise of their gifts which is often lacking in professional performances.’

She and Paul had dreamed of bringing great musicians together to play informally at their home, but they needed to find a more appropriate building in which the creative spirit could be allowed uninhibited expression. That 19a Edith Grove ever became associated with music at all can, in part, be attributed to one work for bowed stringed instruments. It was the Drapers’ discovery that ‘Thibaud’s favourite relaxation was to play first violin in the Mendelssohn Octet’ which made them decide to look for ‘a studio large enough or high enough for eight instruments’.

Unlike many domestic buildings with significant musical associations, 19a is unique in that not only does the original fabric of the building survive intact but the events that took place here a century ago are unusually well documented. We know who played, with whom, when, and what repertoire they played. We also know at which of London’s great concert halls they had just performed before coming to 19a. There are also direct links with compositions that are landmarks in musical history during these vital years of 1911–15 including Szymanowski’s First Violin Concerto and Le Sacré du Printemps. 19a was at the centre of all this.

Click here to read Part Two

The campaign to preserve the residence is supported by leading cultural figures and musicians, including guest editor Steven Isserlis. Download the October 2013 issue to read the news story.

No comments yet