Less than four months before his death, the veteran concertmaster spoke to Heather Kurzbauer about his long career at the forefront of Dutch classical music

Blessed with a sharp wit, keen insight and impeccable manners,

Theo Olof was a delightful Renaissance man. As I spoke to him at

his pleasant abode in the outskirts of his beloved Amsterdam on 21

June (the day his ‘musical twin’, Herman Krebbers was born), I

found that the chance to reminisce brought forth a treasure trove

of memories, all thoughtfully couched in elegant prose. Blessed

with an inquisitive mind, Theo Olof proved his enthusiasm for all

things musical has not diminished over the decades.

Born in Bonn in 1924, Olof saw his early childhood permeated by the

glories of German cultural life. Yet glory turned to vicissitude

after the Nazis came to power. The nine-year-old Olof, accompanied

by his violinist mother, fled to Amsterdam in 1933. Arriving with a

multitude of refugees, the young prodigy had his first encounter

with Lady Luck thanks to a perceptive local volunteer. He was taken

to the legendary Viennese-born pedagogue Oskar Back: ‘My

introduction to 30 years of inspiration.’ Back had a penchant for

Šev?ík exercises and the metronome. Yet beyond the strict

application of metre and method, Back was well versed in the

expansive musical styles of his former master, Eugène Ysaÿe. ‘Back

had a fantastic brain for teaching,’ Olof recalled. ‘He always knew

just what a student’s weak points were and how to work on them. It

was a bit irritating that he always seemed to know whether a

student was prepared – even before a single note was played. We

used to think it had something to do with the way we rang his bell.

If a piece was not properly prepared, I would have to return to his

home for a repeat performance that very same evening.’ Along with

his treasured Šev?ík, Back advocated a broad repertoire reaching

far beyond virtuosic pieces and concertos. He encouraged the young

Olof to expand his horizons by performing sonatas, chamber music

and orchestral repertoire.

Olof’s first taste of the joys of collective music making took

place at Amsterdam’s posh Grand Hotel Krasnapolsky where the young

Theo and his mother played in performances of Carl Zeller’s

operetta, Der Vogelhändler. Olof could hardly contain his

delight as he thought back: ‘It was such a special encounter, to

rehearse with so many people at once and hear so many different

instrumental sounds and colours.’ Portentous remarks from one of

the world’s great concertmasters!

Thanks to Back’s generosity in sharing his considerable network of

contacts and concerts, his star students enjoyed busy concert

schedules. ‘You cannot imagine how pleasurable and instructive this

was,’ he said. ‘Many of the orchestral musicians went out of their

way to offer me guidance, and even gave me small presents. The only

problem was the government police inspector, who doled out fines

for “child labour” after most performances!’ Back’s indelible

influence also nurtured the friendship between his two most

talented pupils, Herman Krebbers and Theo Olof: ‘It all began when

we were assigned to master the Bach ‘Double’ from memory. I think

we may have performed over a thousand times together since then.’

Leading composers including Henk Badings, Géza Frid and Wilhelm

Rettich wrote concertos for them, and as the affable Olof pointed

out: ‘We even managed to get married at more or less the same

time.’

The havoc created by the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands is no

subject for sunny-day interviews. Oskar Back was forced to endure

ludicrous interrogations before a fake non-Aryan identity was

fabricated. Olof narrowly escaped deportation and was forced

underground. Brussels became his safe haven: his name was changed,

his violin career halted. A prolific writer with several Dutch

books to his credit, Olof wove his wartime impressions into a

tribute to the troubled Russian genius in a compelling volume

entitled My Life with Tchaikovsky.

The year 1951 was remarkable for Olof, who not only took fourth

prize at the Queen Elisabeth Competition but joined Herman Krebbers

to share ‘the finest seat in the house’ at the Hague Philharmonic.

Commenting on the challenges of switching from soloist to

orchestral leader, Olof underscored the importance of learning to

blend in with other musical personalities. The concertmaster

operates in ‘the best of all musical worlds’ as a musical spokesman

between conductor, composer and fellow musicians.

The Hague Philharmonic was sociable and relaxed, a bit

undisciplined compared with Olof’s future home orchestra, the Royal

Concertgebouw. ‘Convincing less fanatical colleagues to work hard

in sectionals was quite a challenge at the outset,’ he recalled.

Olof and Krebber’s regime paid off: the Hague Philharmonic reached

new heights of excellence in the late 1950s, with splendid

performances at the Holland Festival, a long list of world

premieres, international tours and a recording contract with

Philips. A champion of contemporary music, Olof added the Hans

Henkemans and Bruno Maderna violin concertos to his commendable

repertoire list during that period.

Many great conductors passed muster as Olof waxed eloquent on the

legends of the past. ‘For me, first and foremost, the grandest of

the maestros was Carlo Maria Giulini,’ he said. ‘Such a refined

gentleman, such wonderful taste and such an exquisite stick

technique that put gesture into encouragement, so that we could

perform with a mixture of reverence and passion.’

And then there was Otto Klemperer, feared by many an orchestral

musician for his autocratic manner and ultra-perfectionism. Olof,

however, relished the fact that the idiosyncratic maestro could

show another side to his complex personality: ‘We once met by

chance in the centre of Amsterdam, the stern maestro walking arm in

arm with his lovely daughter, Lotte. He peered down at me before

asking whether I would join them for an ice cream. And then there

was the time that I was woken up by the telephone in the middle of

the night – Klemperer needed to ascertain then and there if I would

accept the position of concertmaster with the Philharmonia

Orchestra (London).’

Although Olof was to receive many offers to leave the Netherlands,

including the temptation to lead Eugene Ormandy’s Philadelphia

Orchestra, he relished the free time built in to his shared

concertmaster positions. ‘And of course the orchestra had the

luxury to work in Concertgebouw Hall, a wonderful instrument that

is especially kind to orchestras who can play pianissimo.’

Teaching, coaching, commissioning new works and running

masterclasses for orchestral string players to work on excerpts

were all part of Olof’s magical mix of musical activity. A founder

of the Dutch national violin competition in 1967, aptly named the

Oskar Back Competition, he was tireless in developing new venues,

new repertoire and new opportunities for future generations. In the

late 1970s, the ever-inquisitive Olof rediscovered the luthéal, a

mechanically altered piano used in the original scoring of Ravel’s

Tzigane. Olof did not rest until he performed and recorded

the piece with luthéal.

Olof’s final golden nugget of advice: ‘If you must play, if music

is your true calling, practise, practise, practise. Never give up.’

At 88, Olof was as inspiring as ever, a man who practised what he

preached.

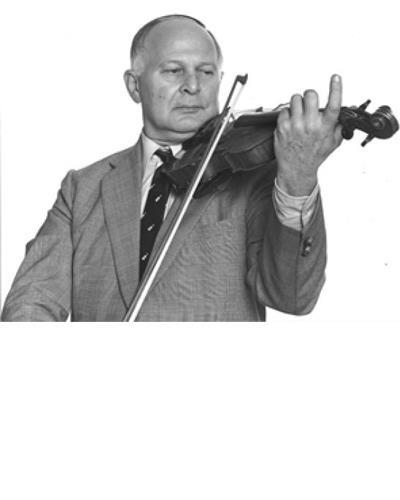

Photo: Theo Olof in 1980. Courtesy Peter Keller

No comments yet