The cellist revealed his thoughts and ideas on performing, practice, technique and musicianship to David Blum in The Strad’s January 1988 issue

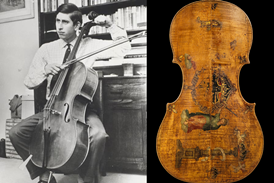

Cellist Yo-Yo Ma...

On becoming a professional cellist

I remember going through a lot of conflict when I was 15 as to whether I wanted to become a musician. Of course, all along playing the cello was something I excelled at. And, with age, I love music more, but that doesn’t mean that I love the profession more. I can still see myself one day not being a professional musician. When a rock once fell on Casals’s hand, his first reaction was, ‘Thank God I never have to play the cello again.’ I pay a price to play an instrument – all the travelling, being away from your family, having to neglect so much that’s fascinating outside of music. And you never know if it’s worth paying that price.’

On practice

I have never practised very much. When I was in high school I only practised about two hours a day. I once practised for four hours a day for a whole month, and was exhilarated. “My God,† I thought, “I’ve actually done that!† Since I don’t like to work hard, I’ve had to become efficient in my practising. I was lucky that, thanks to my father, I had a tremendously good foundation. It’s the concentration that counts. I hated it, but it paid off because I can take a piece today – of 20-25 minutes – and probably learn it in two weeks by working two to three hours a day. This isn’t talent – I’m not extraordinarily gifted in that respect. It comes from the amount of time I’ve put in doing this kind of thing.’

On musical influences

‘You pick up influences from many sources. You hear a great orchestra such as the Berlin Philharmonic and you marvel at the variety of sound it can produce. One needs to experiment a great deal, conceiving a sound-image for every phrase. But it takes time to assimilate some of the influences. Casals, for example, had a 'parlando' quality in his playing. When I was a teenager I had difficulty understanding this, as I was concerned almost exclusively with tying phrases together. Then I became aware of how pianists can create a lyrical line despite the acoustic delay within individual notes. I realised that the kind of articulation Casals achieved is, in fact, essential to communicating on a stringed instrument. For an influence to be meaningful, you have to come to an organic understanding of it. It has to fulfil an aesthetic goal.’

On colour and nuance

‘Variety of nuance is indispensible to all forms of music making. One speaks of a so-called solo sound, chamber music sound, or orchestral sound. But that becomes a moot point when you actually understand the score. In almost all great music you find changes of texture, changes of relationships among the voices. Music schools don’t have to teach the kids how to play in an orchestra; they need to teach them how to play chamber music.’

On vibrato

‘The more you can rely upon the flesh and bones in your arm for vibrato, the better. If you do it just from your hand it takes more energy. Of course this depends on the context: a sudden quick vibrato can easily be produced by the hand. But the weight of the arm is important in producing the basic sonority. In slow passages I find that I get the optimum balance and weight if I keep only one finger on the string at a time. This is particularly important to me as I have thin fingers. The other fingers are held loosely in the air, and this helps the hand to relax.’

On bow arm

‘With the bow arm I try to be efficient, which means to use as much back, shoulder and natural arm weight as I can, and also to push and pull the bow rather than squeeze it. There’s an obvious difference because in pulling against the string you get the richest possible sound, produced with the least effort. Normally my wrist is not very active at the frog. Again, there are places where you’ll want a quick reaction from the wrist for a sudden accent – but then the sound won’t have quite so much weight.’

On intonation

‘Normally I give a lot of attention to intonation. I’ve found that many students are not sufficiently sensitive to the changing role of intonation in the musical context. “Expressive intonation† is part of my playing. You use it for the right emphasis. You can’t always use it if you have to fit a chord, but it’s indispensible for those poignant moments.’

On teaching

‘A good teacher should fill in what the student needs. Flexibility is called for. Every student needs something different. I try to communicate a little of the excitement that I feel. But I learn from my students too, sometimes as much as they learn from me.’

On performance

‘Leon Fleischer put it well when he suggested that a performing musician should divide himself into three persons. Person A looks at the score and tries to understand what it’s all about. Person B tries to express this content with the instrument. Person C is out in the audience, listening and reporting back as to whether Person A’s concepts are actually coming across. Person C is the hardest to develop. Experience counts; you have to work in many different physical conditions, receive comments from friends and colleagues, and listen to your recordings. The best moments come when you feel everything is going well, the message is being conveyed the way you imagine it, you’re at one with the audience, and the audience is concentrated and participating. That’s the goal: the wonderful sense of sharing.’

This interview was taken from a larger article published in The Strad’s January 1988 issue.

No comments yet