Recital programmes should be like a well-balanced meal, and always incorporate tasteful virtuoso pieces, argues the American maestro

Recital programmes have changed dramatically over the past 50 years. In the Golden Era when the illustrious greats of the violin world were in their heyday, recital aficionados thronged to hear the masters show their special gifts in repertoire suited to their styles. The recital programme was varied and always included virtuoso pieces to delight the audience.

I often refer to the recital being like a well balanced meal. Begin with an appetiser to whet the appetite, follow up with the main course and top it off with dessert to please the palette. The format would usually begin with an 18th-century work to set the pace and to establish tone and classic style. This was followed by a major sonata, contemporary or solo works, and then virtuoso pieces, including transcriptions, in many encores. On rare occasions a concerto such as the Vieuxtemps Concerto no.5 or Paganini could even be found in a recital.

Today, violin programmes are not really violin programmes as they are overloaded with sonatas, which put the burden of responsibility on the piano. Rarely do you see the works of violinist composers represented in recitals. Works of Sarasate, Wieniawski and Paganini, that exhibit virtuosity, are rarely played because they have been labelled as trite music. But this is the very reason that recitals have lost the appeal and glamour of yesteryear, and the enthusiasm of the devoted audience. It is a noble cause to programme three Brahms sonatas or four Beethoven sonatas in one programme. But it is hardly a one-man show. Especially when you put a stand on stage and read the music. Recitals are more interesting whenever treated like an art exhibit with works from various periods.

Transcriptions seem to be forbidden in this era. And yet this was the very thing that made icons of artists such as Kreisler and Heifetz, who never omitted them in their recitals. There is a current trend in competitions to include a transcription by the above mentioned in audition tapes. The reason: to see if one has a sense of style. To play these works requires sophistication and taste. So why don't we programme them anymore? Are we becoming such musical snobs?

In planning an interesting programme, think of it like telling a story. I have always used early sonatas by Tartini, Vivaldi, Pasquali, Handel, or works such as Vitali’s Chaconne and La Folia by Corelli to begin the programme. This sets the tone for the listener and gives you the opportunity to ‘warm up’. The first half of the programme should not exceed 40 to 45 minutes of playing time. Personally I have always included a solo work of Bach, Ysaÿe or Paganini, for example, to allow the violin to be heard alone. After the intermission, programme a work that does not exceed 17 to 20 minutes, be it contemporary or in contrast to the first half. Now you begin the fireworks with a tasteful selection of virtuoso pieces by mixing slow and fast moving works. Keep a central idea in mind and not a hodgepodge of unrelated pieces. Second half duration, for best effect, should account for 35 to 40 minutes maximum. Leave the audience wanting and demanding encores. Bring back the ardor and enthusiasm that marked recitals of The Golden Era.

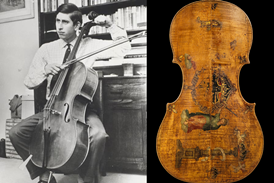

Read Aaron Rosand's first blog for The Strad on producing a beautiful tone here.

No comments yet