A regular, nice, beautiful sound doesn’t interest the music director of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, he told The Strad in this interview from 2008

What do you consider the perfect string section in terms of the way it functions and its sound?

I need to hear a feeling of movement in the section, a flexibility that creates a tone that is always in motion. String players benefit from a physical lilt with the music, which helps create uniformity, but it shouldn’t be exaggerated, as if they’re corn in the wind. Warm-bloodedness and a singing quality are paramount. A regular, nice, beautiful sound doesn’t interest me: I need to hear humanity in it. Players must follow that singing quality with their ears as they play and never abandon it. We live in a society in which everything is shiny and brilliant, and warmth is an underestimated commodity. In music it’s very important.

This singing quality should be maintained at all costs – but it can be a liability, especially when the strings are accompanying. Sometimes you need an incredible glow and intensity of vibrato to wrap a beautiful clarinet or oboe solo in warmth, but when there are several strands going on at once and the string parts are sustained, less vibrato is better. This takes the fog off the windows so that you can see through. It’s important for everybody to understand this, and to be very specific about the necessary degree of vibrato.

As a conductor, do you work on the technical side of sound?

I’m not a string player, but I’ve developed a sense of how to help musicians. With any orchestra there are certain basics: staccato attack normally has to start with the bow on the instrument; in a singing passage the vibrato starts before the note. This ABC of string playing is important, and one always returns to it.

It’s important for me to make the players aware of the lengths of phrases, where we’re going to, where they need to come up, where they need to sustain, where the tone is dropping out. Sometimes these things are to do with the speed of the bow; for example, there’s a natural tendency for the end of a down bow to get softer. As a conductor you have to help them to decide when to play with the tendency and when to fight it. Sometimes string playing is about going against nature.

I’m very interested in speed of bow. When one is playing French music, for example, there are certain effects for which you need a lot of very fast bow, to create an appropriately wispy sound, but in Wagner you must use a slower, sustained bow.

It has become tradition to increase the number of bow changes in order to add sound, so even in a long phrase that could be played in two bows, you often see four bow changes. This is a mistake: the compactness of sound that you get from taking fewer bows is much better.

If I have a strong relationship with an orchestra, we get rid of bowings, returning to the original score. I’ll never forget watching Daniel Barenboim rehearse the finale of Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben. There’s a passage where the strings have a long, slow melody with the horn, and the players were changing bow every bar. Barenboim got rid of 50% of the bowings, and the stillness was immense, just by virtue of the speed of the bow. It is a wonderful effect.

What defines a good concertmaster?

I’m a better conductor when I have a really good concertmaster in the chair. I think this is true of every conductor. Obviously they need talent, and musical antennae that are second to none. A concertmaster faces all sorts of conductors and they can’t remain the same with every one. They have to be open to what each conductor brings but have a strong enough musical personality to keep the line of players in order.

Their tone has to be able to infect the whole orchestra. With a great concertmaster the orchestra alters: the sound of the strings changes, and therefore the warmth of the whole orchestral tone. I try to make use of the individual qualities of each concertmaster, to inspire them to be themselves as much as possible in order to lead the group.

Does that go for other section leaders too?

It does, but the nerve centre is the concertmaster and their relationship to the other leaders. The contact between the front-desk players is very important in orchestral string playing. They have to be looking at each other and breathing together.

I talked before about the movement of the orchestra: when a conductor gives an up-beat and feels the whole orchestra breathing with that up-beat, it makes a huge impact. If nobody moves on the up-beat, it’s not very reassuring, and it’s not very beautiful to look at. The aesthetic aspect is very important – the string section should be like a living body. It’s the front line of the orchestra from a visual perspective.

There’s nothing worse than seeing a string section slouching. Everybody has to convince the audience that the music is great – so the physical attitude is very important in string playing.

Is string sound a national thing or do orchestras have their own individual sound?

Each orchestra has its own innate sound, which is affected by the different cultures and different musical traditions involved. I conduct the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, which is mainly made up of English players, as well as the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, which makes for a very interesting comparison.

By nature the opera orchestra has a more noble sound, a sound that is often wonderfully sustained, which is why they play Wagner so beautifully. Because they’re an opera orchestra, they have an amazing ability to play rubato, and have a uniformity and flexibility of phrasing that symphony orchestras can only dream about.

With the Romans there’s a certain ardour and elegance: it’s a question of temperament. Italian orchestras also have a naturally ecstatic vibrato, which in some contexts may not be palatable, but there’s no question that it commands your attention with its singing nature.

What frustrates you most about string players?

The most important thing in this business is listening. One is always reminding players to listen, especially to listen out for when they’re supposed to be accompanying and when they’re meant to be leading.

What’s your advice to anyone about to do an audition?

Know your excerpts really well. I’ve heard people come in, play the bejesus out of a concerto and then get totally lost in the excerpts. There may be room for a tempo to go one way or another, but within a reasonable margin: some people miss the boat completely. Prepare yourself – even if it means getting a recording and listening to the piece. I tend to judge people on excerpts more than anything else.

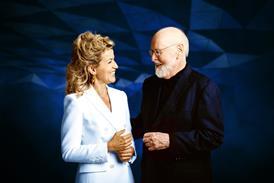

Antonio Pappano is music director of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in London and the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome

Interview by Ariane Todes, first published in The Strad's February 2008 issue

No comments yet