A willingness to engage in challenges outside of our ability level and to embrace making mistakes can help adults to learn as efficiently as young children, argues clarinettist and performance psychology researcher Christine Carter

First published in January 2021

I have always marvelled at the speed of learning in childhood. This became even more remarkable to me when I became a parent three years ago, witnessing the extent of learning that takes place on a daily basis. As with physical growth, there are days when a child’s development is shocking. You wake up and all of sudden a child can do something they couldn’t do the day before. The early years are marked by the sheer volume of days like this, with language, motor skills, and social skills all developing on steep learning curves.

The efficiency of learning in early childhood is often attributed to the astounding neuroplasticity of the child’s brain, especially during particularly malleable ‘critical periods.’ And while this is a fundamental part of the picture, I am struck by another pillar of childhood learning – failure. Watching my son learn to walk I realised just how willing he was to make mistakes and fall. He wasn’t striving for perfection; he was striving to do something he could not yet do. And this immense challenge necessitated mistakes, learning from those mistakes, and constantly recalibrating. He was not concerned about what people would think of him or that he would be labeled a ‘non-walker’ if he did not achieve perfect strides.

When I contrast this with adult learning, the picture looks very different. We are trained from school-age days that mistakes are punishable and should be avoided. Risk-taking in general is viewed as…well…risky. A fear of failure gradually takes root and begins to shape decision making that can greatly interfere with the process of learning. In the adult years, growth-inducing challenges are regularly avoided in favour of learning contexts that are more ego-friendly. Perfectionism replaces growth as the ultimate learning ideal.

This shift in how we approach learning plays out in a variety of ways in the context of music study. Having taught in many contexts, from elementary school beginners to high level conservatory performers, a pattern regarding risk-taking has emerged. The older and more advanced the student, generally the less willing they are to engage in activities that put them outside of their comfort zone. My eight-year-old elementary school beginners eagerly dived into new challenging activities, including tasks they had never before tried, such as improvising and composing.

On the flip side, in a class of upper level university or conservatory students, it can be difficult to convince volunteers to try something new in front of their peers. This is understandable given the cultural emphasis placed on perfection – a particularly prominent feature of training in classical music. But eliminating the possibility to fail also means that we are eliminating many fertile opportunities for learning and growth. How well would children learn how to walk if they were never permitted to fall? How would their reading develop if they were not allowed to make mistakes?

Our adult aversion to challenge and failure also fundamentally influences the way we practise our instruments. We tend to spend long periods of time on the same materials, especially when it comes to technical development. I still remember my first undergraduate lesson. I was given five new daily technical studies all at once – a scale study, a thirds study, an arpeggio study, an articulation study, and a chromatic study – which I had to prepare for the next week. To say that it was a steep learning curve was an understatement. The challenge was immense, but my playing grew in spades that week and the initial weeks that followed.

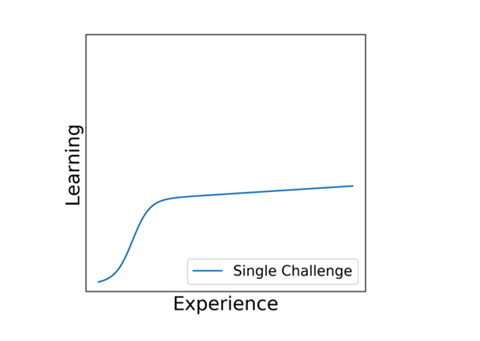

While I also had weekly études that changed, these same daily technical studies stayed with me for years. And although I continued to improve on these tasks, the steep learning curve of those early weeks was replaced by a very slowly inching up plateau. As adult learners, we spend a lot of time in this plateau part of the learning curve, staying with tasks long after the majority of learning has taken place. The following graph demonstrates the initial steep learning curve that accompanies engagement with a new challenge and the plateau that often follows.

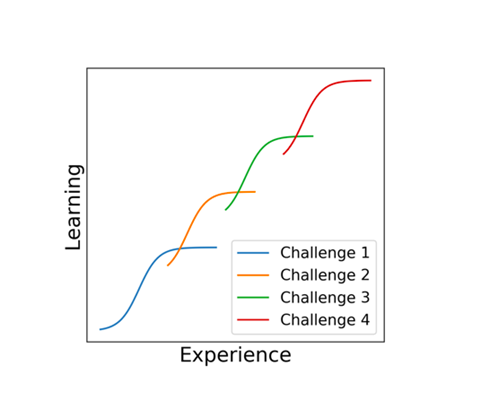

Instead of trying to slowly inch up a plateau, what if we introduced a new challenge right after a learning curve starts to dramatically slow? And then another right after that? These overlapping steep learning curves might look something like the following:

These learning curves are of critical importance if want to optimise our growth as musicians. By taking advantage of the steep learning curves associated with new challenges, we can dramatically increase how much we are able to learn in a set amount of time. For maximum efficiency, we need to spend more time on the growth part of the curve and less time doing the same things over and over again, seated comfortably on the plateau.

While challenge-focused learning may seem counterintuitive to adults trained to avoid errors, especially in high stakes educational settings, this kind of learning is actually quite natural. Not only do we see this kind of learning from the first stages of child development, but we also see it in lower stakes contexts in our adult lives. It’s why video games are so addictive. They tap into our desire to be challenged and perpetually working just outside of our current ability level. As soon as one level is passed, a new harder level is immediately introduced. It’s also why many people like trying new hobbies, when the challenges are rich and the learning curves steep.

So how can we tap into this in our music-making lives? First, and most importantly, we need to recognize when our mental engagement is waning. Mind wandering and the feeling of time passing slowly are usually good signs that we are on a plateau and ready for a new challenge. In general, we want to make sure that we are regularly engaging with new and challenging materials to maximise effortful processing in the brain. Instead of playing the same warm-ups and technical exercises each day, we can introduce new challenges and variability to increase our technical development.

While various technical patterns form the basis of much of our repertoire, they never appear the same way in every piece, so we are not helping ourselves by practising them in a static way. Instead, we can play all of our major and minor scales starting on different scale degrees – in essence, practising all of the different modes. We can also practise them in different groupings (e.g., triplets, groups of four, quintuplets), and with the metronome starting on different subdivisions each day (e.g., having the metronome on the 1st sixteenth of each beat one day followed by the 2nd sixteenth the next day, etc.)

Read: A video-gaming approach to practice will maximise your technical efficiency

Read: Adult string students bring unique challenges which can be very rewarding

We can practise exercises from many different sources, instead of staying with one that is tried and tested. We can also turn to colleagues outside of our area of speciality for new challenging materials. As a classical musician, I frequently ask my jazz-pianist husband for new technical exercises standard in the jazz world, but rarely touched upon in classical studies (e.g., pentatonic patterns and permutations, hexatonic exercises, and approach tone exercises). And of course, we can also make up an infinite number of exercises ourselves. Just like when we were starting out and major/minor scales provided the opportunity for a steep learning curve, we need to find new exercises that will challenge us similarly.

In addition to infusing our practice with more challenging and diverse materials, we can also practice our technique and repertoire in more interesting and varied ways. UCLA researcher Dr. Robert Bjork coined the term ’desirable difficulties’ to refer to a number of manipulations that make practice more challenging, while significantly improving learning. These include interleaving (e.g., alternating practice on different tasks instead of blocking practice on all of one task before moving to the next), variability of practice (e.g., practising passages using a variety of different practice techniques instead of playing front to back in the same way each time), and spacing (e.g., spacing practice sessions throughout the day rather than doing one long massed practiced session). All of these desirable difficulties increase effortful processing in the brain, providing the types of challenges that create steep learning curves.

Contrary to previously held beliefs, adult brains still exhibit remarkable plasticity. Not only are new connections formed and existing connections strengthened, but new neurons are created altogether. This ’neurogenesis’ was long thought to be limited to critical periods in children’s development, however it is now known that neurogenesis continues throughout adulthood.

We need to change the way we approach our practice, optimising challenge and steep learning curves so that we take advantage of the immense learning that we are still capable of. In the words of Robert Bjork: ‘…when embarked on any substantial learning enterprise we should probably find the absence, not the presence of errors, mistakes, and difficulties to be distressing – a sign that we are not exposing ourselves to the kinds of conditions that most facilitate our learning, and our self-assessment of that learning’. Just as in childhood, adulthood is a time for engaging in challenges outside of our ability level, making mistakes, and growing from what we learn from these mistakes.

Read: Adult beginner cello: Never too late to learn

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #46: Billy Tobenkin on starting the cello at 25

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Jody Culham and Dr. Aaron Hodgson for providing such helpful feedback on the first draft of this article and Rebekka Lagacé-Cusiac for creating the illustrations.

Biography

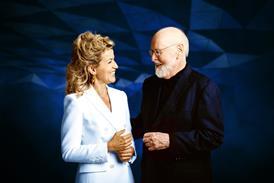

Dr. Christine Carter is interested in how musicians can be more effective on stage and in the practice room. Her research has led to a variety of article publications and invitations to give workshops at dozens of institutions around the world. She is a Visiting Scholar at Dr. Jessica Grahn’s Music and Neuroscience Lab (Western University) and recently launched The Curious Musician blog to explore performance psychology topics of interest to musicians.

Christine is also an active clarinetist. Performances have taken her across the globe, from Carnegie Hall to the Sydney Opera House. She completed her Doctor of Musical Arts at Manhattan School of Music, where she taught the Woodwind Lab for 4 years, and is now Associate Professor of Music at Memorial University in Canada. Christine is a Buffet Crampon Artist.

1 Readers' comment