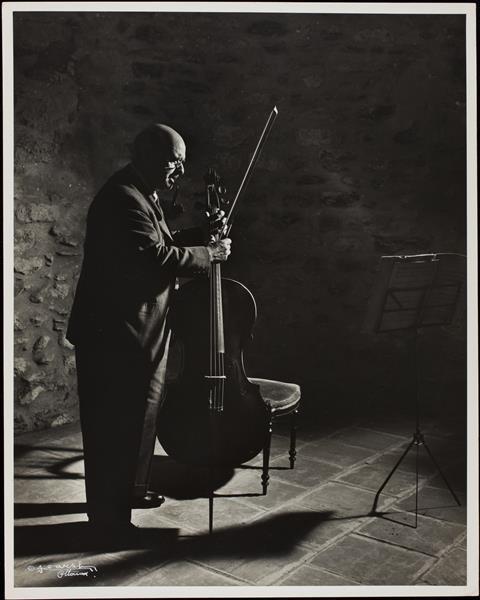

To mark the 50th anniversary of the death of Pablo Casals in October 1973, Oskar Falta examines the great Catalan cellist’s ‘rediscovery’ of the Bach Cello Suites, and the continuing legacy of his highly personal approach to the music

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

Read more premium content for subscribers here

This article was published in the October 2023 issue of The Strad. Read the digital edition here.

‘You play Bach your way, I’ll play him his way,’ concluded the celebrated harpsichordist Wanda Landowska after a discussion she had with Pablo Casals. Looking back at Casals’ interpretation of Bach’s Cello Suites BWV1007–12 and how he brought these works into the limelight, could we come to a closer understanding of what really was his way?

Casals first came across an edition of the Cello Suites in Barcelona in 1890, when he was 13 years old. Owing to the absence of musicological research at the time and several biographers’ blind trust in Casals’ word, the story surrounding the discovery contains some apocryphal elements. ‘Suddenly I came upon a sheaf of pages, crumbled and discoloured with age,’ he recalled in Albert E. Kahn’s book Joys and Sorrows: Reflections by Pablo Casals (1970). Along the same lines, Robert Baldock’s 1992 biography of Casals describes his find as ‘battered’, and Eric Siblin in his popular volume The Cello Suites (2009) gives an account of the score being discovered amid ‘musty bundles of sheet music’, portraying its cover as ‘tobacco-coloured’. These sources give such a strong and mysterious impression of antiquity, as if Casals had just chanced upon the long-lost manuscript in Bach’s own hand. And yet, if the score was in such a miserable state, age was not the cause, as it was published only 24 years previously.

Unfortunately for Casals, what he had found was an 1866 ‘concert’ edition of the Cello Suites by the German cellist Friedrich Grützmacher (as first reported in 1962 in Joan Alavedra’s Pau Casals). Grützmacher is infamous for having taken remarkable liberties in editing works of great composers. Some of his alterations included additional chords, completely recomposed passages, alternative endings, added dynamic and glissando markings and, last but not least, the Sixth Suite transposed from D to G major. The extent of Grützmacher’s musical vandalism left some of the movements edited beyond recognition (Casals’ own first copy is now on display in the Pau Casals Museum on Sant Salvador beach, El Vendrell, Spain).

Apparently, Casals was also not the first cellist to perform an entire Bach suite in public (a fact long known to researchers), as he liked to claim: ‘Before I did, neither violinists or violoncellists had ever played a suite in its entirety’ (Josep Maria Corredor: Conversations with Casals, 1956). Casals’ oft-repeated astonishment that these works were known neither to his teacher José García nor to anyone else in his circle didn’t mean that they were unknown universally. At the turn of the 20th century, Barcelona lagged far behind other European centres when it came to classical music.

In fact, from the publication of the first edition of the Cello Suites in Paris in 1824 (a century after their conception) until 1890, when Casals first learnt of their existence, they had been not only edited and published repeatedly but also performed. A number of 19th-century cellists played an entire Bach suite in concert: Grützmacher in 1867, Alfredo Piatti in 1873, and Julius Klengel in 1894 and 1904, according to George Kennaway’s summary. Casals himself started including a complete suite in his concert programmes in around 1902. By then, he must have long realised his Grützmacher score was a cheat, especially if he got his hands on other, less modified editions in the meantime (to Grützmacher’s credit, he also made another, more conservative version around 1867).

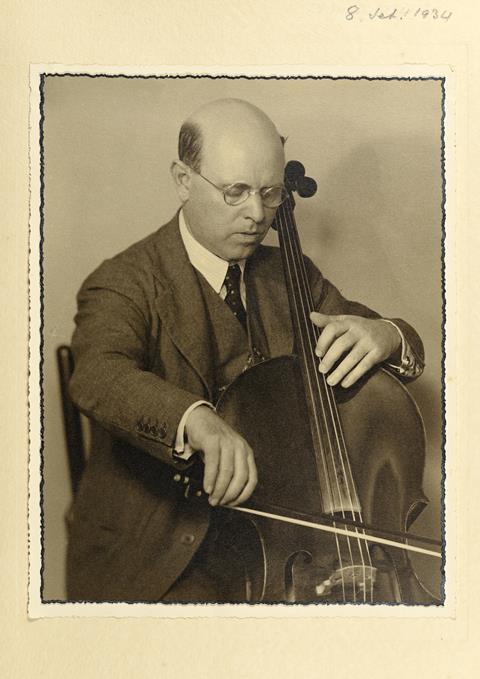

Actually, according to the cellist Colin Hampton (1911–96), Casals’ favourite edition was Robert Hausmann’s (1898). He had also known Anna Magdalena Bach’s manuscript, since it was printed in Diran Alexanian’s analytical edition in 1929. If Casals neither discovered the Cello Suites nor gave their premiere performance, he was indeed the first cellist to record them. Although he had already recorded a selection from the Third Suite as early as 1915 in New York, his true masterpiece was his recording of the entire set, created in London and Paris between 1936 and 1939.

While certain aspects of Casals’ playing style and interpretation might appear anachronistic today, others still hold water

The first complete Bach Suites recording was made in three instalments under tragic historical circumstances. Casals’ homeland, Spain, was already in the midst of civil war when he started recording, and by the time he’d finished, the Second World War was looming on the horizon. On top of all this, Casals was not particularly fond of recording and reportedly hated the microphone, which he called the ‘steel monster’. The first recording sessions (suites nos.2 and 3) took place in London in November 1936. Around the same time, the British government refused to deliver arms to Spanish anti-Franco republicans, an act that made Casals reluctant to return to England to continue the recording process.

A recording of the entire set of suites may never have seen the light of day were it not for Casals’ student and friend Maurice Eisenberg (1900–72), who was based in Paris at the time and who in 1968 recalled, ‘I took the bull by the horns and asked Mr Fred Gaisberg, the record executive, if he would consider moving all the bulky and expensive equipment to Paris.’

And so the Bach marathon could resume with suites nos.1 and 6 in the French capital in June 1938. Recording conditions at that time were far from ideal: each side of a 12-inch 78rpm disc had about 4–5 minutes of recording time available, and although splitting a movement between two or more disc sides wasn’t uncommon, Casals left out some of the repeats. Moreover, every movement had to be recorded in one take, without the possibility of cuts or further editing.

With two suites left to record, times weren’t getting any brighter: Casals was in Barcelona while the city was being captured, and he escaped to France by the skin of his teeth.

The lack of news from his family in Spain left him worried, and witnessing the misery of war refugees, whom he aided on the other side of the border, made him feel no better. How Casals managed to gather the force to record the rest (suites nos.4 and 5) is beyond comprehension – but he did so in June 1939, again in Paris. The set was issued on 78rpm discs by the Victor label in three instalments (in 1940, 1941 and 1950 respectively), but the LP records weren’t released until 1957. Casals wasn’t quite satisfied with the result – owing to technical flaws of the recording technology, he found that the sound lacked the dynamism and variety of a live performance. This is why he enjoyed hearing his records played faster. ‘He did not mind too much if, owing to the higher speed, the works sounded roughly a minor 3rd too high, to him it was more important to regain the lost liveliness,’ remembered the Swiss cellist Rudolf von Tobel (1903–95) in the introduction to his edition of the Bach Cello Suites based on Casals’ interpretations (published in 2004 by Carus Verlag).

From 1936 onwards, von Tobel studied the Bach Suites with Casals literally measure by measure and kept notes pedantically. While certain aspects of Casals’ playing style and interpretation observed by von Tobel might appear somewhat anachronistic today, others still hold water – in particular, certain features of his left-hand technique. According to von Tobel, Casals generally favoured open strings and lower positions in Bach. In permanent search of left-hand relaxation, he chose his fingerings accordingly. For example, he might prefer a harmonic to a stopped note; thus, by taking advantage of the resonance overlap, he gained extra time for release and preparation of the hand for the subsequent position. Casals’ employment of extensions was an effective means of shift avoidance. He used stretches not only between fingers 1 and 4, spanning an interval of a 4th (on the same string) or an octave (across two neighbouring strings), but also between 1 and 2, beyond the usual whole-tone extension, applying the same spider-like principle to spans between fingers 2 and 4. For repeated notes played with the same finger, Casals would lift up the finger each time (where applicable) before quickly placing it anew, which proved to be an efficient tension-release device.

In general, he preferred using stronger fingers to weak ones and avoided trills with 3 and 4 – instead, he often used 2 and 3, in favour of expressive intonation (these two fingers allow for narrower semitones, as they share the same tendon). For ascending passages, he used strong audible finger articulation, and for descending ones, a sideways left-hand pizzicato with each finger leaving the string. As much as he is credited for reducing the use of bidirectional portamento in cello playing, there were occasions when Casals indulged in fervent glissandos as if there were no tomorrow.

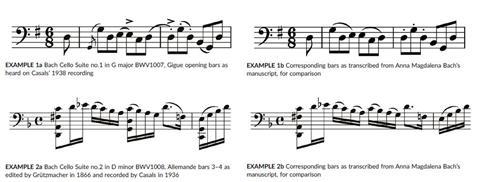

But how does Casals’ rendition of Bach sound to today’s ear? Stravinsky blamed him for ‘playing Bach in the style of Brahms’. On his recording, some movements do indeed sound more Brahmsian than others (for example, the Prelude and Gigue from the Fifth Suite), while some (the Third Suite’s Courante, for one) would almost meet today’s expectations. Let’s also bear in mind that Casals’ cello set-up was surprisingly close to ‘Baroque’, as he played on gut strings all his active musical life. In his approach to Bach’s musical text, Casals was less heretical than Grützmacher, but traces of the latter’s influence are apparent especially in the first three suites. Although it appeared in earlier pre-Grützmacher editions, one such example is Casals’ syncopated articulation in the Gigue of Suite no.1 (example 1a). Casals defended it with the following argument, which was as disarming as it was invalid: ‘To have true respect for the music means rendering it with as much life and as beautifully as possible.’

In other instances, Casals copied Grützmacher almost literally (example 2a). Other than that, Casals didn’t hesitate to add a few chords or double-stops, or to change a note here and there (whether out of conviction or convenience), and while he adopted some of Anna Magdalena Bach’s bowings, he discarded others as ‘unplayable’.

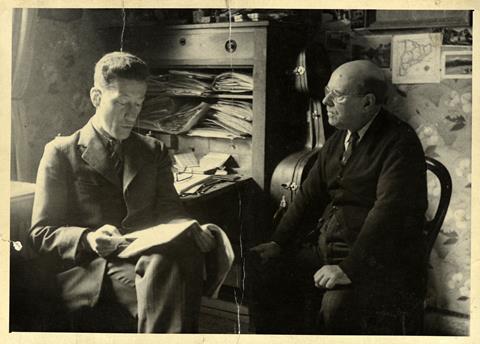

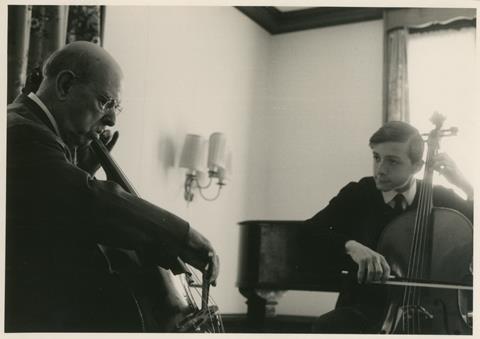

Naturally, the legend of Casals hasn’t left younger generations indifferent. Although he never held a permanent teaching position, he always generously shared his ideas with young players. In the 1920s, he gave annual masterclasses at the École Normale de Musique de Paris and taught a few select private students during his exile in Prades. The next such opportunity didn’t arise until 1952, the year that saw the inauguration of the Zermatt Summer Music Academy, which ran until 1965. Set in the idyllic Swiss Alpine resort, each annual edition welcomed around fifty international participants and countless auditors (including Casals’ friend Queen Elisabeth of Belgium). In a local newspaper interview (quoted in Helga Váradi’s Le maître et le centimaître, 2021), Casals spoke of the academy’s higher purpose: ‘The student should learn not only how to play better, but also how to become a better human being.’ Anna Shuttleworth (1927–2021), who attended the classes in 1954, remembered the lessons fondly: ‘Casals always made encouraging remarks before making other suggestions to improve the performance.’

However, some participants were not at ease with the sycophantic atmosphere in Zermatt. ‘There seemed to be a real cult of adulation,’ recalled violinist Alexander Schneider (1908–93) in his unpublished memoir ‘Sasha’ (1988). In spite of himself, the cellist in his later life became a sort of a musical guru, as the young and rebellious Jacqueline du Pré – who ‘was not comfortable with the aura of saintliness that surrounded Casals’ – noticed in 1960 (Elizabeth Wilson, Jacqueline du Pré: Her Life, Her Music, Her Legend, 1999). Von Tobel took minutes of the classes, and ‘would immediately write down whatever Casals said whenever he opened his mouth’, recalled Schneider, before going on: ‘At one point during the lesson, Casals stopped a student and said, “No, no, no, this is wrong – you have to do this and this.” Right away, von Tobel stood up and said, “Master, just now you said the contrary about what this same student played last year.” Casals answered, “That was last year.”’ A masterclass setting can often turn into an enforcement on students of the teacher’s own interpretation; nevertheless, in his address to the participants, Casals would remain open-minded: ‘You have to take the responsibility for your performance and are under no obligation to do something just because I said it. But I have always spoken from the heart in my hope of helping you’ (as recalled by von Tobel in his edition of the suites).

In his Bach interpretations, Casals represented both a catalyst and an inhibitor to progress, as it was difficult to escape his influence and avoid emulation for decades to come. He wasn’t open to ideas of historically informed practice and called anyone who didn’t share his own opinion a ‘purist’. In an attempt to protect Casals from critique by the emerging early music movement, authors like von Tobel or David Blum (Casals and the Art of Interpretation, 1977) implied that by pure intuition Casals came to the same conclusions as 18th-century theorists such as Johann Joachim Quantz or Leopold Mozart, whereas in fact he was reformulating perennial musical knowledge. Casals’ celebrity – augmented by several extramusical factors, like the dawn of recording and radio, his political activism and his marriage to a much younger former student – reached international stardom in his later life and unfortunately partly eclipsed other great cellists who came both before and during his lifetime. Nevertheless, one thing is sure: there will always be Bach Cello Suites before and after Casals.

Now, 50 years after Casals’ passing, cellists are still adding their share to the sky-scraping pile of recordings of the Bach Cello Suites. More often than not limited by self-imposed restrictions (be it the idealistic pursuit of authenticity or the necessity to use appropriate historical equipment), have we perhaps come full circle so that we could once more take a leaf out of Casals’ book, enjoy certain liberties and get inspired by his way? Casals once said: ‘Sometimes it is better not to play the way it is written down,’ or, to put it more bluntly, in the words of the American jazz musician Miles Davis: ‘Don’t play what’s there, play what’s not there.’

The Casals legacy

The Pau Casals Foundation is a private, non-profit organisation created by Pablo and Marta Casals in 1972. Its aim is to preserve and disseminate Casals’ artistic and humanitarian legacy, support young cellists and encourage projects promoting the values he stood for throughout his life on behalf of peace, human rights and social commitment.

The Pau Casals Museum (right) is located in Casals’ summer house on the beachfront of Sant Salvador, in the municipality of El Vendrell, Spain. It became his habitual residence from the 1920s onwards. Casals lived there until the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939, before he went into exile. The museum presents an interactive, dynamic and participatory experience that explains the figure of Casals in all his dimensions as a musician as well as reinforcing the humanitarian side of his legacy. For more information, visit www.paucasals.org

Read: Cellist Pablo Casals on expressive intonation

Read: Bach Cello Suites: What do we really know about Bach’s Cello Suites?

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

Read more premium content for subscribers here

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

2 Readers' comments