Its fate was almost to be consigned to the murky depths of an Uruguayan river but it continues to delight and inspire audiences of the present day. Alessandra Barabaschi delves into the dramatic life of the ‘Mara’ Strad

Given the turbulent history of the 1711 ‘Mara’ Stradivari cello, its chief fascination may be the fact that it exists at all. That it retains the appearance of a majestic golden-period Strad, with a bright and brilliant sound to match, is something of a miracle – and testimony to the skill of the Hill restorers of five decades ago. When one considers that its fate was almost to be consigned to the murky depths of the River Plate in Uruguay, one can see why the cello’s 306-year history was even turned into a novel, by German author Wolf Wondratschek in 2003 – with the cello itself as narrator.

Considered one of the finest examples of Antonio Stradivari’s ‘B form’, the ‘Mara’ boasts a spectacular two-piece back of fairly tight-grained, deeply flamed maple, sloping strongly upward from the centre joint. The remaining original varnish, spread over a transparent cinnamon-gold ground, is a brilliant orange, particularly evident around the C-bouts and ribs on the bass side.

Now played by Christian Poltéra, for 16 years it was used by his tutor, Heinrich Schiff, in tandem with the 1739 ‘Sleeping Beauty’ Montagnana. ‘Heinrich had the luxury of having two of the best cellos on earth to choose from,’ remarks Vienna-based luthier Marcel Richters, who has taken care of the ‘Mara’ for almost two decades.

‘He knew exactly which one to use for each piece. The “Mara” has an outstanding soprano voice, whereas the Montagnana has lots of darkness. You might say that between them, they represent the difference in tonal ideas between Cremona and Venice. The Venetian model has a broad middle and slightly higher arching, which gives a more bassy, mysterious tone. Very generally speaking, Cremonese instruments can have a more singing, soprano voice with high overtones.’

Indeed, Richters’ first encounter with the ‘Mara’ came when Schiff brought it to him, concerned that it was actually too brilliant and intense. ‘It almost sounded like a French instrument,’ he recalls. ‘There was too much treble in the sound, with a consequent lack of colours. It might seem like a loud instrument for that reason, although that’s an illusion – no cello can be too loud.’ To bring out a warmer sound, Richters designed a new Frenchstyle bridge, lowered the neck angle and experimented with different strings until Schiff was satisfied. Poltéra has retained the same set-up since he began playing it in 2012, four years before Schiff’s death.

Traces of alcoholic liquor, having been upset and allowed to drip from the top to the bottom sides, removing the beautiful varnish on its downward course, are still discernible.

For such a bright instrument, the ‘Mara’ has had a somewhat dark history. Its first known owner, from whom it takes its name, was the German cellist Johann Baptist Mara (1744–1808). The son of one of the earliest recorded Bohemian cellists, Ignaz Mara, he is mentioned in the history books more in terms of his ill temper than for his musical prowess.

The oboist William Thomas Parke was outspoken in his criticism of him in his Musical Memoirs of 1788. ‘Mr Mara in his performance displayed more rapidity than taste,’ he noted, ‘and his attitude whilst playing was not very graceful. It gave one the idea of a coachman on his box, in the act of driving.’ It may have been Mara’s partiality to alcohol that accounted for such a damning report; and also for his reproachful behaviour towards his wife, the renowned opera singer Gertrud Elisabeth Schmeling (below left), to whom Goethe dedicated two poems.

Parke recorded in 1787 that ‘Mr Mara, who did not possess the tenth part of his wife’s talent, loved her and his bottle equally, and frequently broke the head of one and cracked the other.’ Mara’s misdeeds were even referenced in the Hills’ book Antonio Stradivari, His Life and Work, given their effects on his instrument that they could still perceive in 1902. ‘Unfortunately his violoncello seems to have suffered somewhat from his viciousness. Traces of alcoholic liquor, having been upset and allowed to drip from the top to the bottom sides, removing the beautiful varnish on its downward course, are still discernible.’

Mara had brought the cello over to England in 1784. After his wife separated from him in 1799 he lost his main source of income and, soon after, in 1802, he was forced to sell his instrument. It was bought by one of the leading cellists of the time, John Crosdill (c.1751–1825), who was appointed chamber musician to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, and cello teacher to the Prince of Wales.

From this point on, the value of the ‘Mara’ continually rose: in 1808 John Betts (1752–1823) bought the instrument from Crosdill for the sum of £100, and sold it shortly afterwards for £150 to amateur cellist William Champion. In 1810 it was auctioned at Phillips in London, where it was bought by Godfrey Bosville Macdonald, the third Baron Macdonald of Sleat (1775–1832), for £210. The next owner was the English cellist and conductor Charles Lucas (1808–69), who played in Italian opera houses. Around 1860 it was purchased by a banker named John Whitmore Isaac (1807–84, above right) for roughly £300.

It seems to have left the Isaac family when the estate and house passed to Isaac’s grandson. It then went back to the Hills, who found a new customer for it: Alessandro Pezze (1835–1914), teacher of the renowned cellist Leo Stern. Pezze acquired the instrument in December 1887 and played on it for 15 years. In 1902 he sold it to amateur cellist H.J. Gardner, who kept it until 1908 when he brought it back to the Hills.

Two years later the ‘Mara’ was bought by wealthy Argentinian industrialist Carlos Alfredo Tornquist Altgelt (1885–1953) and spent more than 20 years in South America. It was bought from Tornquist Altgelt by amateur player Murray Lees who kept it until his death, when it went back to the Hills. On 9 July 1954 they sold it to professional cellist Amedeo Baldovino (1916–98) of Rome.

It was while the ‘Mara’ was in Baldovino’s custody that disaster struck. He had owned it for nine years by that time, and the previous year had joined the celebrated Trio di Trieste. While on a concert tour of the Americas, he and the other members of the trio, violinist Renato Zanettovich and pianist Dario De Rosa, found themselves stuck in Montevideo when their plane to Buenos Aires was grounded by fog. After long hours of uncertainty, the group decided to take a river steamer.

They embarked in the evening and started their journey on the River Plate. They should have reached their destination the following day, in time for their next appointment. At 4.30am, with only 30 miles to go to Buenos Aires, Baldovino was awoken by a shout of ‘Salvavidas!’ (‘Lifebelts!’). ‘I saw that they were starting to fight over the lifeboats, and I understood that things could go badly,’ Baldovino wrote later. ‘I only had my cello; everything else had remained in my cabin. All of a sudden I saw a flame under the bridge.

Suddenly, everyone was aware that their lives were hanging in the balance. One can only imagine the panic that ensued. There was pushing and shoving towards the lifeboats, which seemed to be jammed in their positions, all except for one which was lowered into the sea, and then turned over through having too many passengers.’ With his two companions, Baldovino managed to throw some life rafts overboard, then jumped into the river after them.

‘I don’t know exactly when I abandoned the “Mara”. My instinct for survival took over the reality of what was happening.’ He was picked up by a lifeboat several hours later, and made it to Buenos Aires: ‘I confess that for a long time I did not think of the “Mara”… it was when I awoke the next morning that the enormous significance of the loss of my “Mara” hit me.’

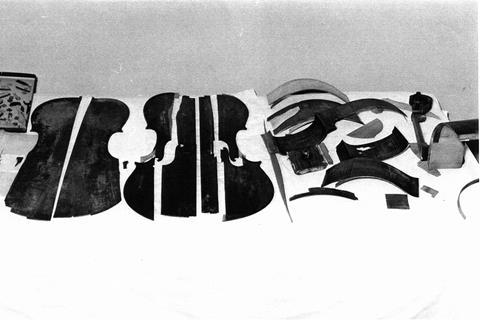

When the news spread that the ‘Mara’ had been rescued, Baldovino could not believe it. The cello case had indeed been found with the instrument inside – or what was left of it. ‘At first sight it was not an instrument that appeared, but a quantity of pieces which I tried avidly to identify, putting them together as well as I could as a possible reconstruction of the “Mara”. In a short time I realised that it could not be done. It was impossible to distinguish between all the fragments.’

It took the Hills seven hundred hours over nine months, at a cost of £1,000, to bring the instrument back to its outstanding shape and tonal qualities. Baldovino continued to perform on it until a few years before he died, calling it ‘my master and trusty friend for almost 42 years’. The cello went back to the Hills and was then acquired by J.&A. Beare, which sold it in 1996 to a German industrialist, who loaned it to Heinrich Schiff.

Such is the strange and unusual history of the ‘Mara’ Stradivari, which continues to delight and inspire audiences of the present day, in the hands of Christian Poltéra.

WATCH: Christian Poltéra performs the Sarabande from Bach’s First Cello Suite on the ‘Mara’

No comments yet