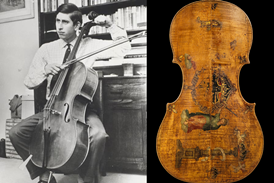

These photographs of a cutaway viola by Otto Erdesz appeared in the May 1991 issue of The Strad alongside an interview with Israeli violist Rivka Golani, who still plays the instrument to this day. An extract of the article by Mark Pappenheim is below

Given Golani’s success with the Elgar/Tertis Concerto, it was perhaps prophetic that her own first instrument was in fact a Tertis Model, presented to Ödön Partos by Lionel Tertis himself and passed on to Golani by her teacher. ‘I played on this instrument for two years,’ Golani recalls. ‘Then, on one of my tours to America, still as a student, I bought an Erdesz viola. That was two years before I met the maker.’

In any other context, our interview might have ended there, with a neat, ‘Reader, she married him.’ But in this case the marriage ended not so happily-ever-after …

…

Her music still benefits from her (ex)husband’s other lasting legacy – the unique custom-made ‘cut-away’ viola which he designed for her and which she has proudly played for the past 13 years. As Golani explains, the problem with ‘conventional’ instruments (if one can even use such a term of the viola) is that while smaller instruments may have very beautiful high notes, and larger instruments very beautiful low notes, there are none that offer both at the same time. She doesn’t quite claim that her Erdesz is the perfect answer but it’s the best she’s heard. ‘It’s built very asymmetrically, with the sides towards the A string narrower than those towards the C. Also the right shoulder is cut away. So I have almost no wolfs at all and the C is very deep and cello-like, while in the higher register I have over an octave more than a normal viola.’

Despite its obvious advantages, though, not to mention Golani’s own vigorous championship, the Erdesz design has yet to catch on. One reason, of course, is the cachet string players still tend to attach to the possession of designer-label antiques. Golani herself admits to owning an old Italian instrument as well, although its make is unknown. ‘Two strings are very beautiful,’ she concedes, ‘but it’s not beautiful all round. And certain repertoire – Bartók, Walton, Hindemith – I really would not choose to play on this instrument. Maybe I’m a bit wild, but I feel I need a bit more resistance, a larger range of dynamics. I don’t always look for sweetness and beauty all the time. It’s like in visual art – not everything is beautiful and shiny. It depends on what you look for. I want more than that. I want everything, like when you cry or you laugh – the extremes. Some people would get scared of it – but not me.

No comments yet